| Focus on Beating |

Marcy Petrini

June, 2023

I am finally back teaching beginning weaving, after the long COVID pause. I love the enthusiasm of students dressing their looms and starting their projects.

Weaving has many technical parts. If followed carefully, we can avoid mistakes: winding the correct number of warp ends, threading the heddles, sleying the reed, tying the treadles. Relatively easy to check and easy to show students how to avoid the pitfalls, although it takes a bit of experience to learn it all.

Then it’s time to tie the warp and getting the tension even across its width. Not so cut and dried. I pat a student’s warp and I may say: “feel the second bout, it’s a bit looser than the others “. What does “a bit looser” mean, exactly? Students learn the way we have learned, feeling, trying and observing. When spreading the warp, if a section sags, it is not tied with the same tension as the others. It can fixed.

Finally, it is time to weave – with an even beat, meaning the same number of picks per inch (ppi) throughout the fabric. Not so cut and dried either!

For a balanced fabric we try a beat that matches the sett (ends per inch, epi). We may have to adjust. Maybe the pattern will show better if we beat a little more closely. Perhaps we want to beat a little more openly to avoid a stiff fabric.

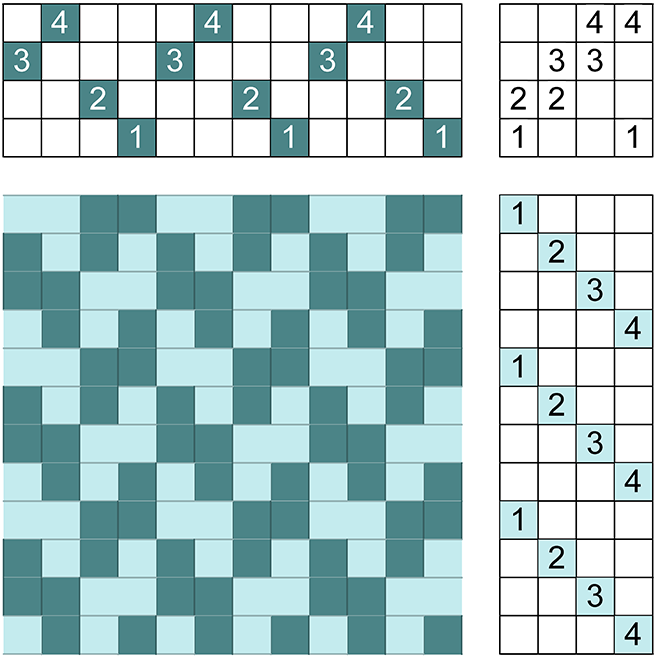

Once decided on a beat, it must be maintained throughout the weaving. We measure often as we learn what the fabric should look like. In my class, beginners are weaving tabby at a sett of 12 epi. For a perfect tabby, the beat should be 12 ppi. However, I say that it’s ok if sometimes it’s 13 ppi, while others it’s 11 ppi. What we don’t want to happen is to creep up: first it’s 13, then 14, then 15 ppi, etc. until the fabric becomes stiff as cardboard! Loser and loser is also not good, but in my experience that doesn’t happen very often. It’s beating too hard that can be a problem. We need some space between threads (as shown by the arrow below), to allow for wet finishing to fill in.

When weavers demonstrate, to outsiders it looks like all we do is throw the shuttle. Beginners learn that they must pay attention to several things to make good cloth, including the treadling steps, the beat and the selvages.

For an even beat, the good question is: how often to measure? For my own weaving, I usually measure every time I start weaving. I take breaks often, but checking the number of threads in an inch is quick. I like to use an “incher”, which I normally use to determine the wraps per inch of a yarn, but of course a ruler or a measuring tape work just as well. If the fabric has a pattern, I can count the number of pattern repeats (and portions of it) in an inch rather than threads. Below there are 6 repeats, 4 picks each, for a total of 24 ppi.

Once weaving, I pay attention to the look of the fabric. “Stay in the moment” or “go with the flow” are phrases used to describe the concentration needed to accomplish the task.

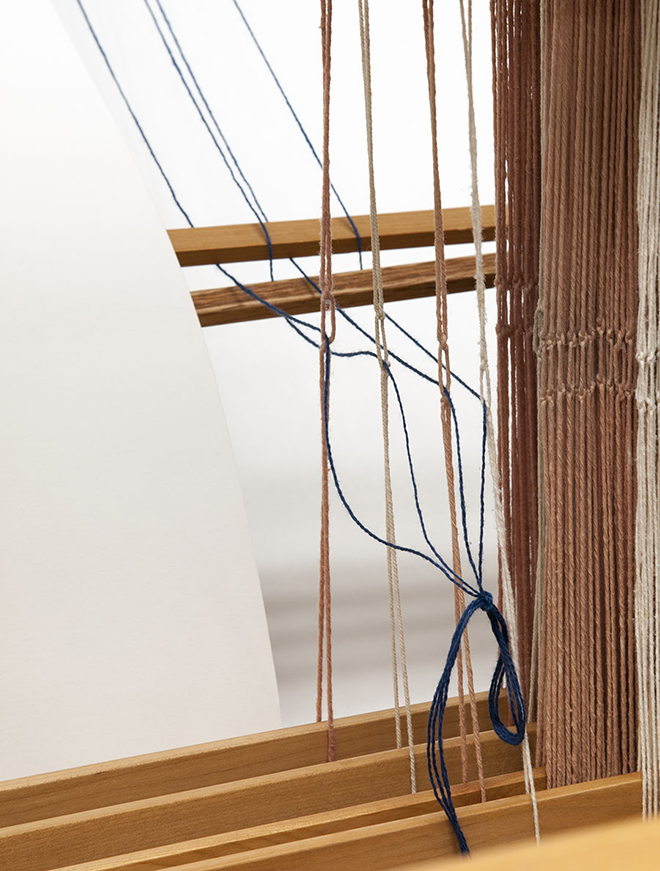

Recently I found out how important paying attention really is. My 101-year-old Mom has been slowly deteriorating and as I write this, she is in hospice. I have always found solace in my handwork during difficult times. Watching this decline in my Mom has been painful and sad. I realized that I was distracted, too, but I didn’t realize how much until I looked at the current piece on my four-shaft loom, shown below.

It is a scarf, variegated orange silk warp with stripes of a different variegated silk. The weft is blue silk. You can see how varied the beat is throughout the small amount woven, approximately 7”. I see five different areas, ranging from weft dominant to too loosely beaten with elongated warp floats and everything in between. No treadling errors and the selvages are acceptable, but I just couldn’t stay focused to get the good rhythm needed for a good beat.

When the stress will be over, the weft will come off and I will rethink the project. Maybe another weft would give me a fresh start.

Happy weaving!

Marcy

| More on Floating Selvages |

Marcy Petrini

May, 2023

Last month I talked about instances when floating selvages may be needed and when they are not helpful. For all the other grey areas, we saw how we use a drawdown to determine whether floating selvages should be added.

Some questions arose: How about unbalanced twills? What happens with more than four shafts? What about weaving with two wefts? Good questions. Let’s examine those.

Unbalanced Twills and Satins

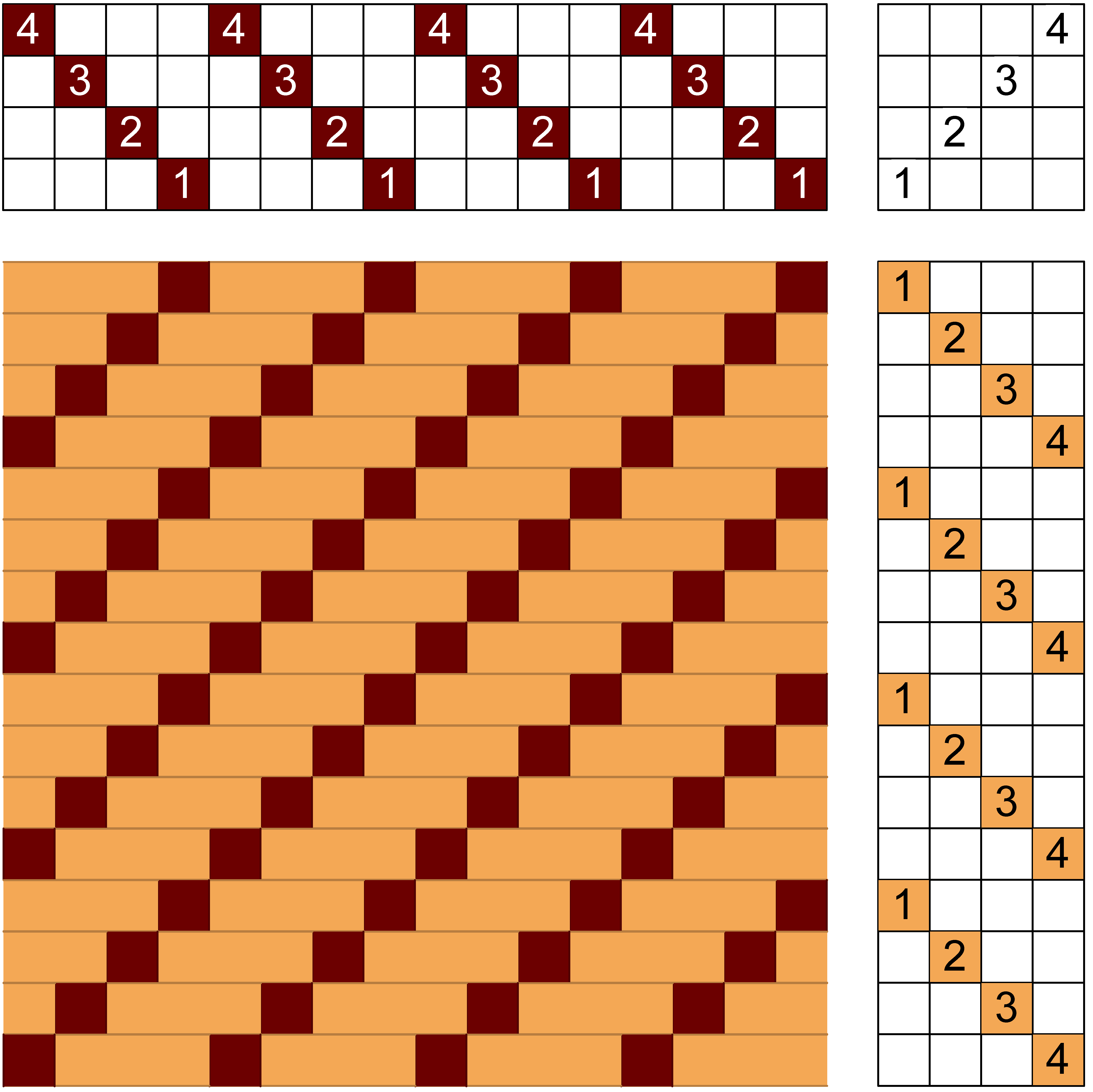

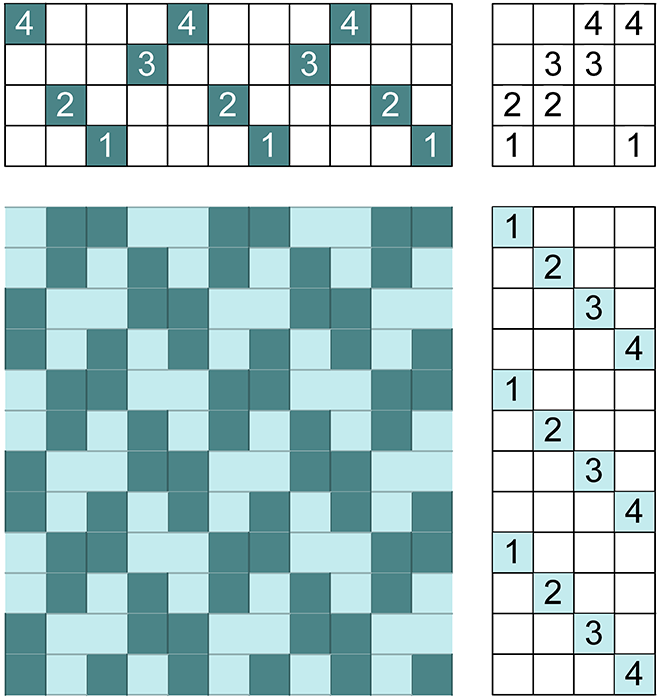

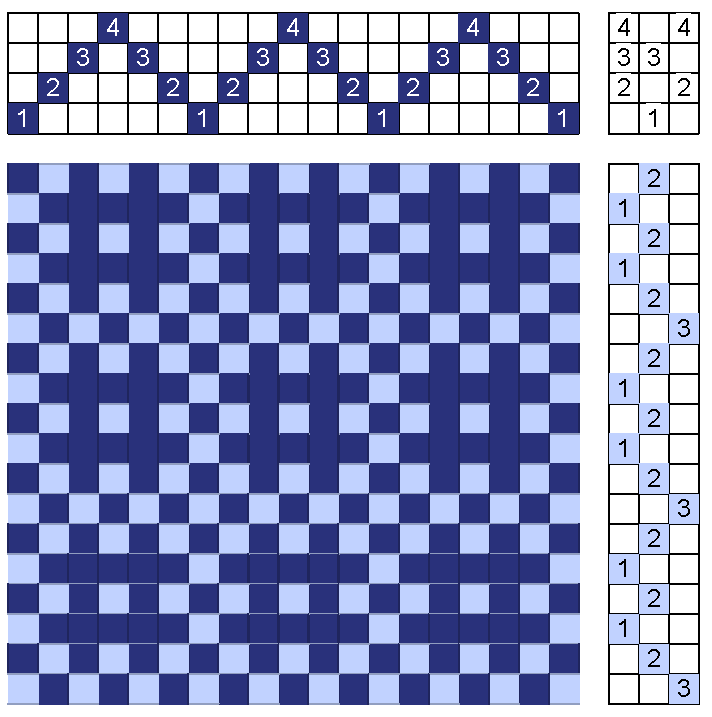

Below is the drawdown for a 1/3 twill. Without even doing the analysis of the drawdown, we can see that we have three wefts in a row at each selvage. Floating selvages are needed.

Here are the two sides of the fabric.

A 1/3 (or 3/1) broken twill has the same characteristics. It is often called a false satin, which it resembles.

True satins require at least 5 shafts. They, too, need floating selvages. The drawdown below shows four wefts in a row at each selvage.

Here are the two sides of the fabric.

Eight-Shaft Twills

Many multi-shaft twills require floating selvages, but, if unsure, we can use the same method we used for four-shaft twills (see the April 2023 blog for a refresher).

Below is the drawdown of a 3/2/1/2 straight twill. If we start the analysis going from the left to the right, we encounter two wefts together at the end of the first pick and the beginning of the second. If we start the analysis from the left to the right, we encounter two wefts at the end of the fourth and the beginning of the fifth pick.

The fabric is below:

Pointed twills on eight shafts similarly require floating selvages. Twill blocks are usually made up of weft-dominant and warp-dominant twills, so they, too, need floating selvages.

Rectangular Float Weaves

Many rectangular float weaves – grouped weaves and unit weaves –have a threading for plain weave selvages on four shafts, which can be extended to more. These do not require floating selvages.

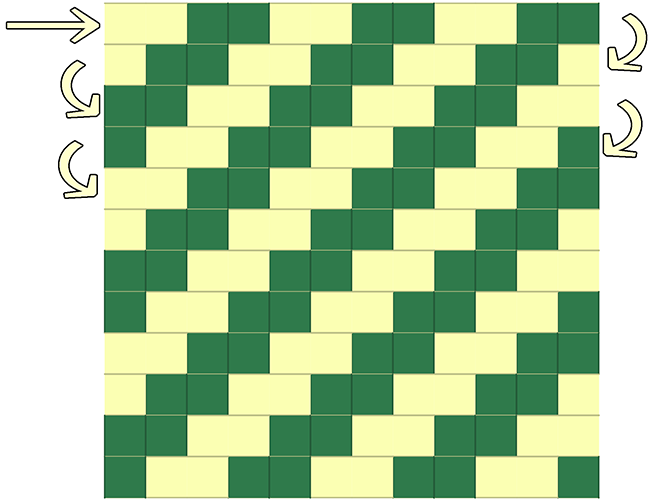

Below is a simple drawdown showing the two blocks of grouped weave huck on four shafts; the threading on shafts 1 and 2 produces plain weave down the selvages.

In the drawdown there are four threads on each side, but it could be more or less, as long as the 1, 2 order is maintained. The fabric below has a 30-thread selvage.

The same threading sequence of shafts 1 and 2 produces a plain weave selvage on the 8-shaft huck as shown in the drawdown below. Floating selvages are not needed.

Bronson Lace has similar characteristics. It is a unit weave since both blocks can be woven together, as shown at the bottom of the first drawdown, Alternating shafts 1 and 2 in the threading produces plain weave selvages, obviating the need for floating selvages. This is true for the four-shaft version in the first drawdown as well as the eight-shaft version in the second.

Weaving with Two Wefts

To avoid floating selvages when weaving with two wefts, we can catch one weft with the other by placing the shuttles in order.

For example, right now I am weaving double weave using Jennifer Moore’s squares. I want my selvages joined. I could use a floating selvage, but this is what I do instead: I use a yellow weft for the top layer; I use a blue weft for the bottom layer. When I am done with the second pick, I place the shuttle with the blue weft in front of the shuttle with the yellow weft. At the subsequent pick with yellow, the blue weft is caught at the selvage in the loop of the yellow weft. This happens on both sides of the cloth.

How we position the shuttle with the weft to be caught depends on what we are weaving, how many colors, and the color order. At the beginning of the weaving we can determine the position needed to catch the weft; we then proceed consistently for the rest of the weaving.

Happy weaving!

Marcy

| To Float or not to Float |

Marcy Petrini

April, 2023

Whenever I teach, the question of floating selvages invariably comes up. When our weft doesn’t catch the warps at the edge, what can we do?

One solution offered by weavers is to place the shuttle over or under the first and last warp thread with every pick. This is not a very efficient way to weave. On the other extreme are those who always use floating selvages. When they are not needed, this is not the most efficient way to weave either, and it may not give us the best edges.

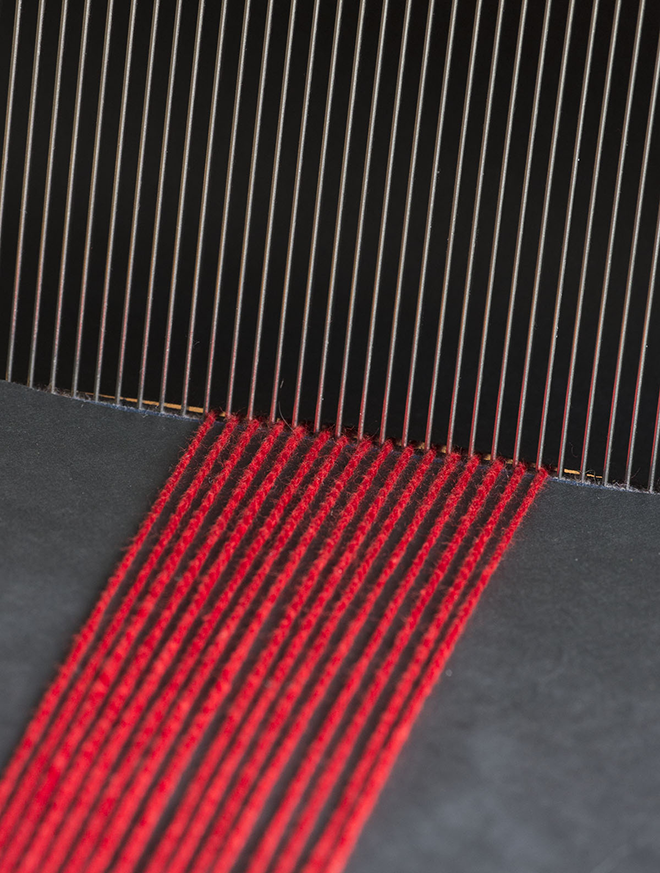

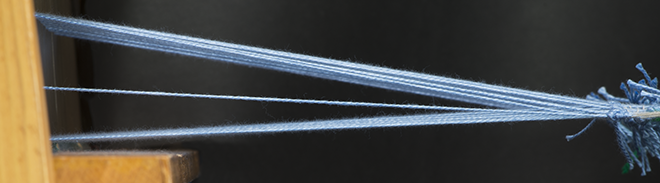

Floating selvages are warp threads that are NOT threaded through the heddles but are sleyed in the reed to space them correctly. Then, when the shed is opened, these warp threads “float” between the top and the bottom of the shed as show in the picture below.

In weaving, we enter the shed over the floating selvage, and we let the shuttle travel on its race; it will end up below the floating selvage on the other side. “Over, under” is a good way to remember. A one-thread plain weave selvage is formed. We could do “under, over” but it is easier to start over as the shuttle ends up under automatically.

Because the take-up of the floating selvages is generally different than that of the rest of the fabric, tension problems at the selvages can result. To avoid this, it’s best to tension the floating selvages separately. I hang them from the back beam as shown below. Old film canisters work well, but they are becoming rare. Weighted bobbins from kumihimo braids work even better, easy to unroll the threads as the warp is advanced.

How to Determine if Floating Selvages Are Needed

In the summer 2014 issue of Shuttle Spindle & Dyepot, in my “Right from the Start” article I described the circumstances when the outer warp threads get caught by the weft and when they don’t. I used the edge warp and weft yarns on a simple loom to describe the various situations. If you are comfortable with drawdowns, however, they can be used as well.

Below are guidelines for looking at the drawdown to determine if floating selvages are needed. The process is easier to understand visually, so examples follow.

- The drawdown should have two complete repeats of the threading and treadling, with any balancing threads or motifs, and picks. It doesn’t matter whether the drawdown is rising or sinking shed.

- Choose a side from which the weft enters the shed; the pick will travel toward the other side.

- On arrival, the weft will be caught by the warp if it encounters it as the last warp thread of the pick OR as the first warp thread of the subsequent pick.

- If caught, proceed to the next pick until the entire treadling sequence is tested, ending with the start of the second sequence.

- If the weft is not caught at some point, start over with the weft entering from the opposite side.

- Repeat steps #3 and #4. If the weft is still not caught, floating selvages are needed.

Plain Weave Example

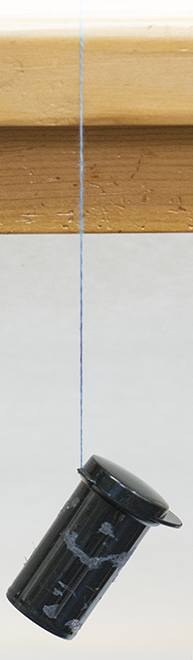

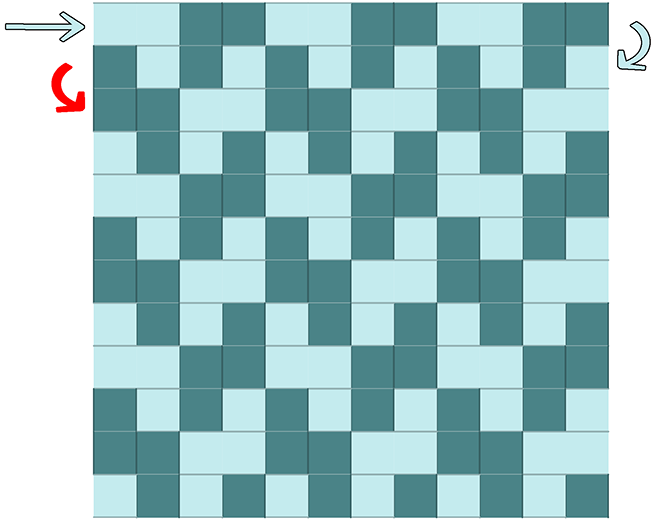

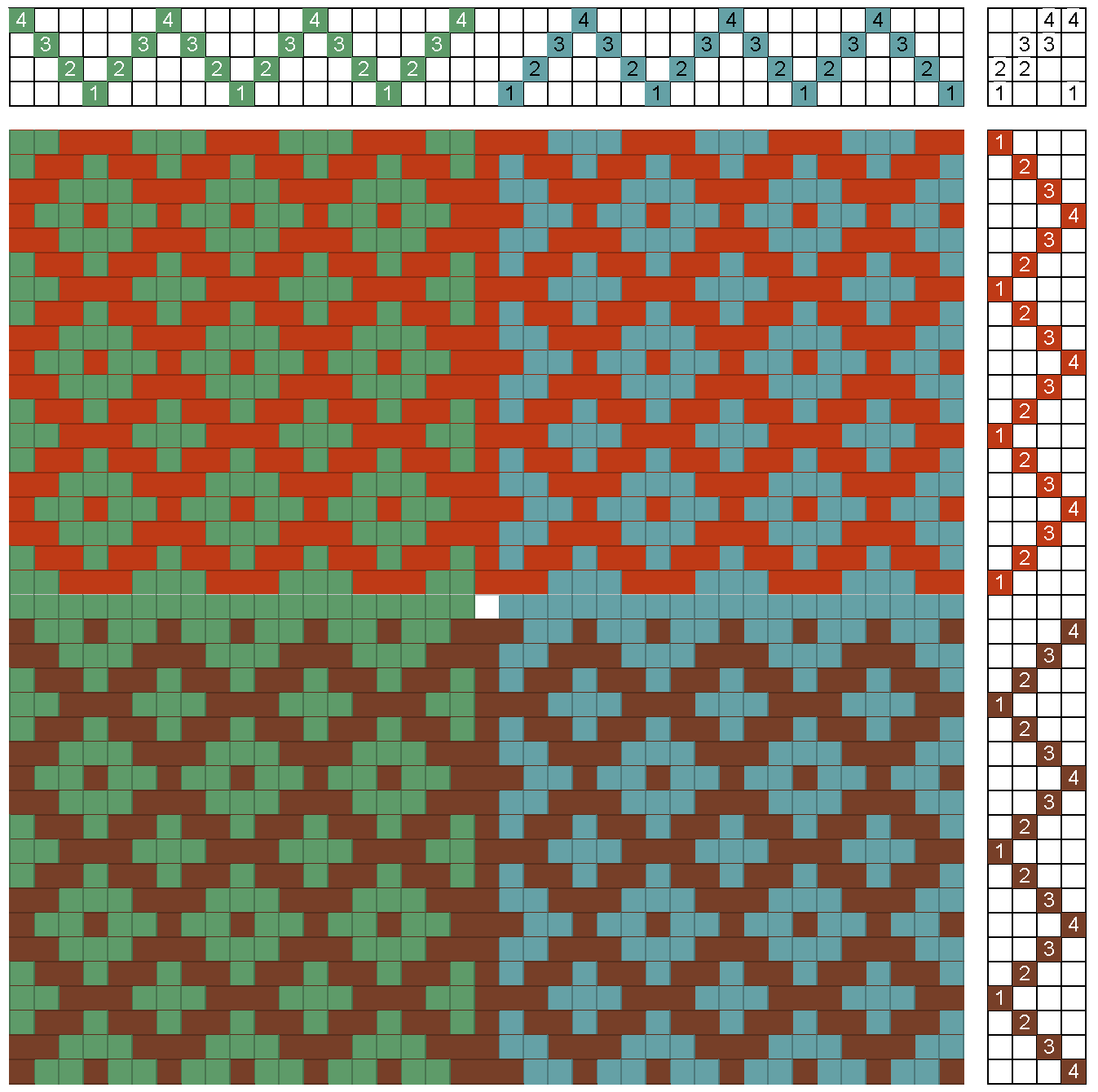

We know that plain weave does not need floating selvages because every weft is caught by the warp at the end. Below is the drawdown of plain weave with a dark blue warp and a light blue weft. This is how we can tell from the drawdown that floating selvages are not needed:

The weft enters the shed on the right as shown by the straight arrow; when the weft exists and enters the next shed on the left, we have warp - weft. At the end of the second pick and the beginning of the next, we have weft - warp. Both picks are successful, no floating selvages are needed.

Straight Twill Example: Reversing the Direction of the Weft

In the drawdown of the straight twill below, the warp is green, the weft is yellow. There are four treadling steps, each of which will need to be tested to determine whether floating selvages are needed.

We again enter the weft on the right. As it exists, we find weft – weft. The warp doesn’t catch the weft as shown by the red arrow.

Before we decide on floating selvages, we can reverse the direction of the first pick by starting on the left as shown by the straight arrow

We obtain warp – weft, weft-warp, etc. at the selvages for the entire sequence, four picks, concluding at the beginning of the next repeat, as shown by the curved arrows.

No floating selvages are needed.

For the straight twill and twills derived from it, there is a useful rule: start the threading with an odd shaft and end it with an even shaft, or vice versa, then enter the shuttle on the side of the warp where the first thread is down. From the example above, we see that when we follow the rule, no floating selvages were needed.

Pointed Twill Example: Floating Selvages Needed

Below is the drawdown for the pointed twill. The warp is burgundy, the weft pink. There is a thread on shaft 1 to balance the threading repeat. The treadling has six steps.

Starting on the right, we encounter weft – weft on the second pick.

If we start from the left, we also encounter weft – weft on the second pick,

Sometimes omitting balancing threads results in a good selvage. The drawdown below shows the warp - warp we encounter when omitting the balancing thread on shaft 1.

Reversing the direction of the weft fails at the 4th repeat.

Floating selvages are needed.

Broken Twill Example: Modifying the Twill

A broken twill is a straight twill where the threading sequence has been modified to avoid the straight twill line. In the drawdown below, the break occurs between shafts 3 and 4. This results in the threading starting and ending with odd shafts, 1 and 3 respectively. Not surprisingly, floating selvages are needed, even if we start where the first thread is down.

We can, however, eliminate one thread, so that the threading starts on an odd shaft (1) and ends on an even shed (4)

We can see from the drawdown below that the problem is solved.

No floating selvages needed.

Specific to the broken twill, we could put the break between shafts 2 and 3, thus maintaining the start and finish with an odd (1) and even (4) shaft.

In general, besides changing the edges of a twill, adding a straight twill repeat at the beginning and end of the pattern may work in avoiding floating selvages. This gives better results with twills based on a straight twill than those on pointed twill, but the class of this structure is so varied that it is worth considering with a drawdown.

When Floating Selvages Are Not Needed: Rectangular Float Weaves

Rectangular float weaves include grouped weaves like huck, unit weaves like Bronson lace, canvas weaves and a variety of other structures that are based on plain weave.

Most often these weaving structures include threading for plain weave along the length of the fabric, obviating the need for floating selvages.

Below is an example of huck lace. The plain weave selvage is threaded on shafts 1 and 2. No floating selvage needed.

Still unsure?

For planning purposes, I like to determine whether I need floating selvages before I start warping. This may be because I am using the width of the loom or I have limited yarn, so I may have to plan for the floating selvage threads.

With some structures, however, it can be confusing to determine from the drawdown whether floating selvages are needed or not; this includes long treadling sequences and some weaving structures with two wefts.

In these cases, I dress the loom without floating selvages. Then I treadle the sequence until the weft is not caught, or I complete the entire repeat plus the first pick of the second. If no floating selvages are needed, I am ready to weave.

If the weft doesn’t get caught with one of the picks, I try reversing the direction of the shuttle. If that doesn’t work, I add floating selvages. Since they are tensioned separately, it is actually easier to add them after the rest warp is tied on. Then I am ready to weave.

Use floating selvages on both sides of the fabric, even if only one side is needed. The two edges of the fabric will look the same and thus more even if they are treated the same way.

Happy weaving!

Marcy

| Greek Huck |

Marcy Petrini

March, 2023

Last year at Convergence® I presented a seminar on “Rectangular Float Weaves” which include huck. Along the way I realized that Droppdräll is the word for huck in Swedish. I found references with the help of my study group colleague Peggy Cole. I wrote about Droppdräll in my March, April and June 2022 blogs. The Swedish are very inventive with this weaving structure.

A few months after Convergence®, I received an email from Peggy asking me whether I knew about Greek huck. Greek huck? Never heard of it. Peggy said that it was in the Manual of Swedish Weaving (by Ulla Cyrus-Zetterström) on page 47.

I had read the book a long time ago, but I had used it as a reference more recently, getting ready for my seminar. I looked it up and no Greek huck on page 47. I looked in the index, but I didn’t find it. I browsed through the huck section and there it was on page 52. I have the 1950 edition, so I figured that the pagination changed and Peggy must have a different edition.

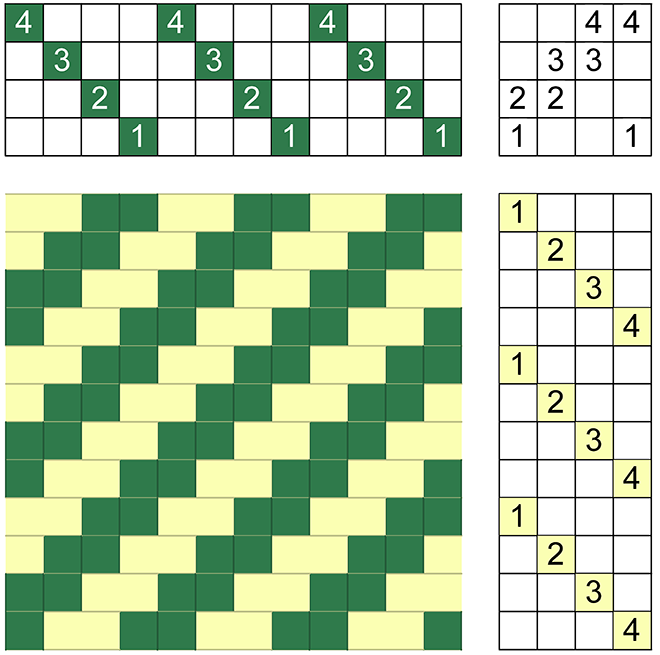

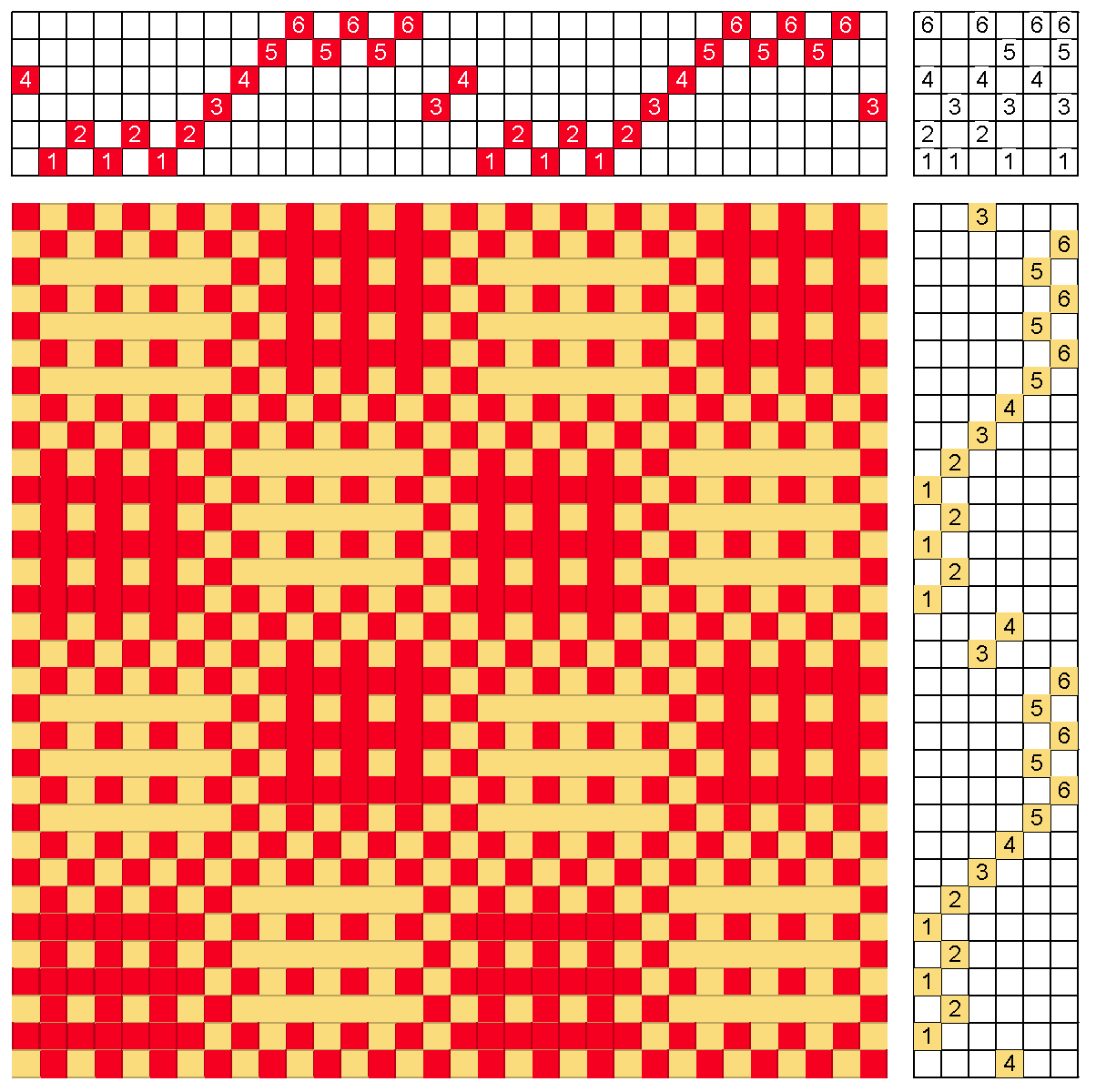

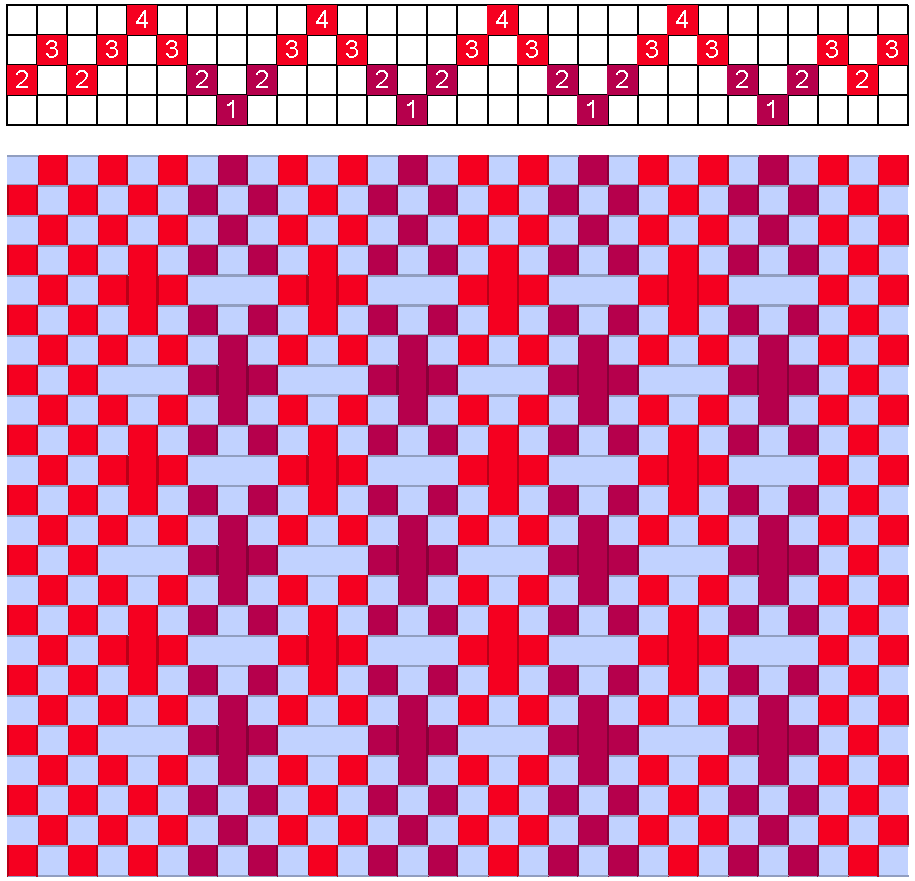

Now I was intrigued. To study a structure, I have to do a drawdown so that I can understand the warp and weft intersections. Here it is:

It’s a 6-shaft huck. I wasn’t surprised as I have come across other 6-shaft structures in the huck family from Swedish weaving sources.

I showed the drawdown at our next study group meeting and I said that I wasn’t sure that the two extra shafts for Greek huck added much; the blocks are staggered by one pick which, according to the author, makes the fabric more stable. I thought that rather than weaving two blocks for a 6-shaft huck, I would prefer weaving six blocks on eight shafts with regular huck.

The next day, Peggy sends me the drawdown for the Greek huck from her book, the 1977 edition: four shafts. On a pointed twill threading! There is that pointed threading again!

Now I was really intrigued! I was thinking that I would put a sample on my four-shaft loom after I finished weaving the scarf I was planning.

For the scarf I was looking for a twill so that the light would shimmer, but I couldn’t really find anything that caught my attention. The scarf is a retirement present for a friend. I seldom weave for non-family members or other non-weavers, but this is a special friend to both Terry and I, and I know he will appreciate the scarf.

In the middle of planning, I thought: he doesn’t need a scarf that shimmers. He needs a scarf to keep him warm since he moved to his native New England after his retirement. Maybe Greek huck would work! I decided to try it.

For warp I used a tussah silk noil from my stash, variegated in blues and purples. Despite the fact that it is labelled noil, the yarn is strong enough for warp. It wraps at 24 epi; for the pointed threading, I sett it at 18.

For weft I used 100% mink from Mini Lotus Yarns, black. It also wraps at 24 epi, but it is squishy, as a worsted-spun yarn may be. I thought it would work well with the silk warp.

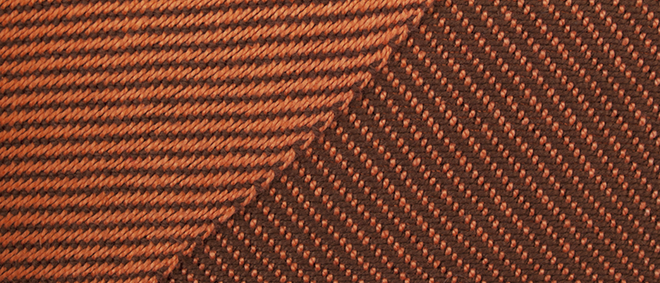

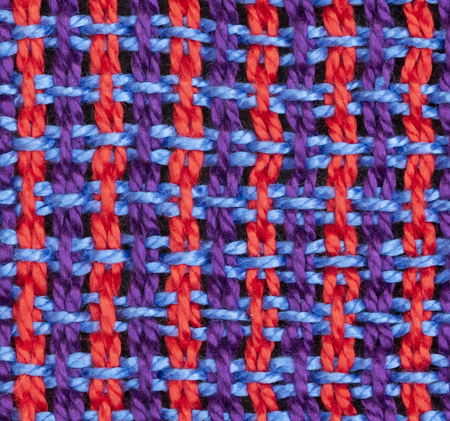

And here is the scarf. I am really pleased with it.

The front and the back of the fabric are different. As woven, the front is warp-dominant, the back weft dominant.

The scarf is wonderfully soft and drapeable, probably the combination of the yarns and structure. Now I am inspired to try Greek huck with other yarns.

Try Greek huck, yet another option on a pointed threading.

Happy weaving!

Marcy

P.S.

The wonderful thing about teaching weaving, besides meeting great weavers, is that I always learn something. Earlier this month I was in San Diego offering two workshops to two talented group of weavers (with overlapping memberships): the San Diego Creative Weavers’ Guild and the Palomar Handweavers and Spinners Guild.

While attending one of the workshops, Liz Jones showed me the drawdown software that her engineer husband, Scott Jones, wrote for her. And even nicer than knowing about it, is using it! So far is available for Windows platforms with more to come, he says. It is free (with no ads!) available for downloading from Scott’s website:

https://www.quickdrawweaving.com/

The software is really intuitive to use, but if you are new to drawdown software, there is a YouTube Channel that provides a tutorial. The videos are also accessible from the website above.

When you download the file to your computer, you may get questions about whether it is safe to do so. That’s a pretty common question asked by a computer system when downloading what we call “executable files” – files that do functional operation. It is perfectly safe to download Scott’s software, I have done it. Many of you know how ticky I am about clicking on links, etc. for fear of being hacked. Scott’s software is safe, he is one of the good guys.

So click through the warnings pages, unzip the files that get downloaded and run the quickdraw.exe file to operate the software.

| Pointed and Reverse Pointed Twill |

Marcy Petrini

February, 2023

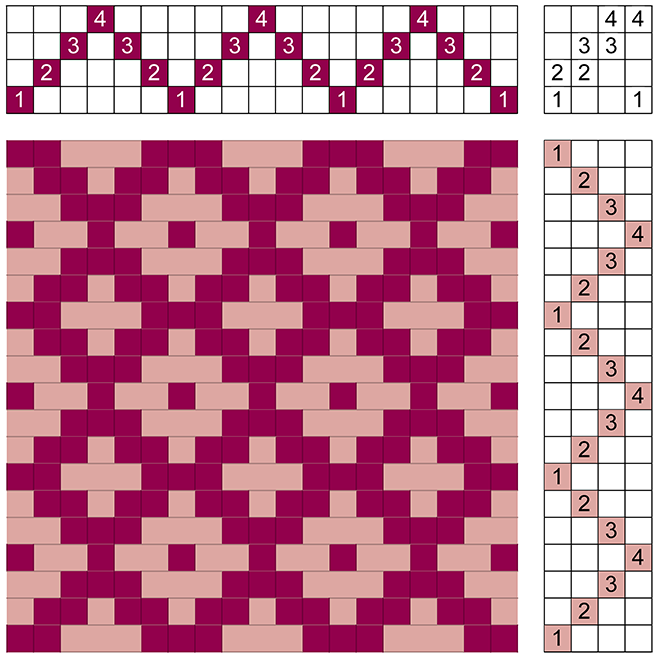

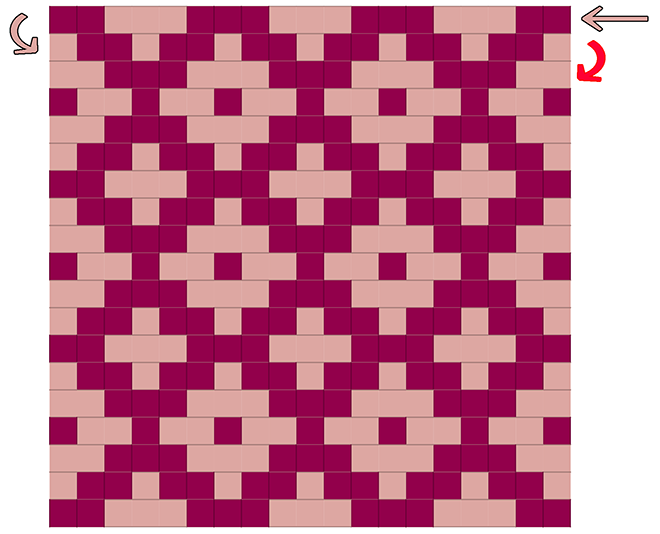

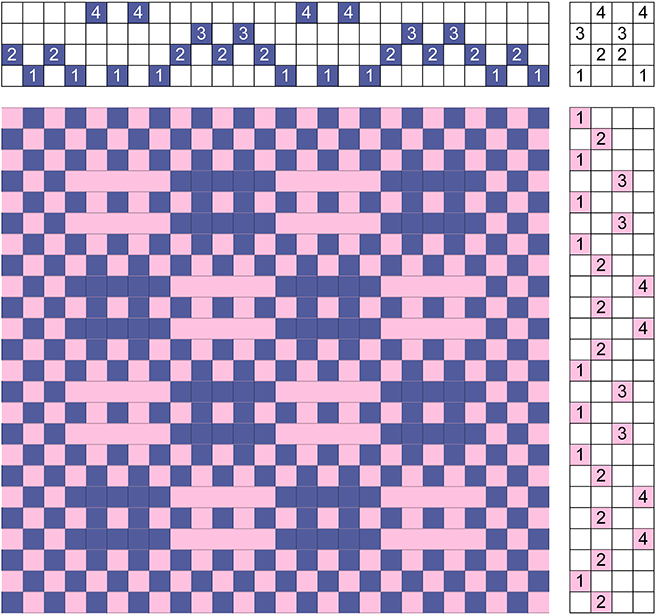

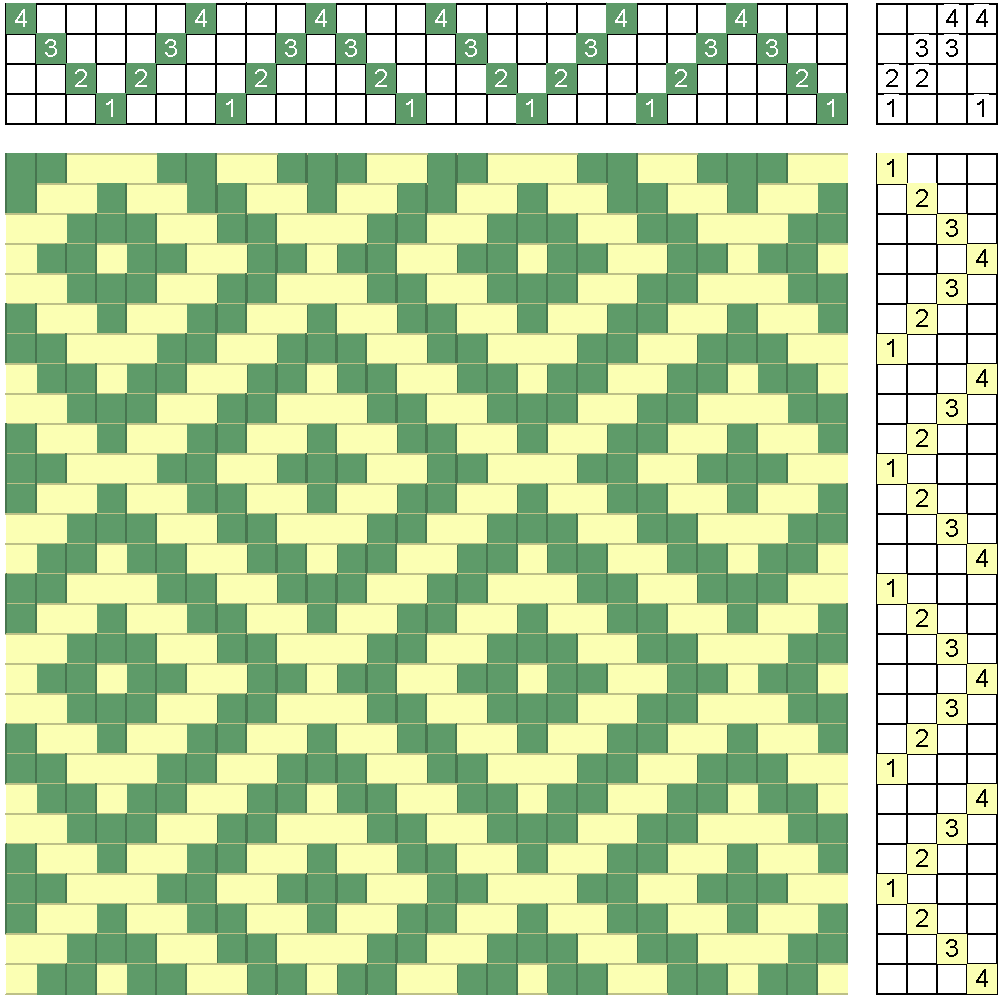

While I was weaving the scarf from the January blog, I was thinking about the versatility of the pointed twill. Davison calls the twill from which I derive my motif a Bird’s Eye twill. No matter what we call it, the pointed and reversed pointed twill weave the same fabric, as shown in the drawdown below.

The best option to weave the fabric using the drawdown, is the blue and brown quadrant (bottom right), where a full motif starts the repeat.

The utility of having the two distinct twills is that they can be combined to form new motifs, for example, the one in the following drawdown. Similar to the previous, but bolder.

Besides the various combinations of pointed and reverse twills and all the twill treadling possibilities, the pointed twill is used for other structures.

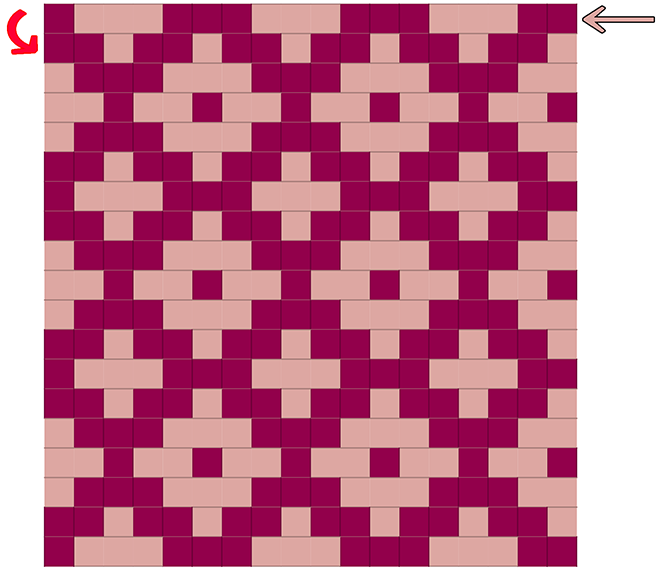

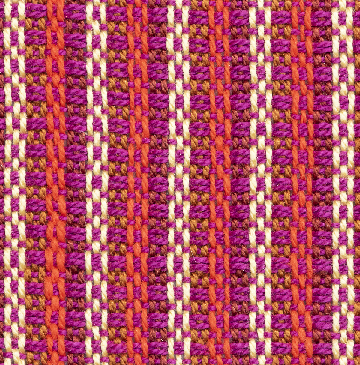

Myggtjäll or “mosquito netting” has a couple of different threadings. Mary Snider in her book Lace and Lacey Weaves uses a pointed twill. Here is the drawdown and fabric sample.

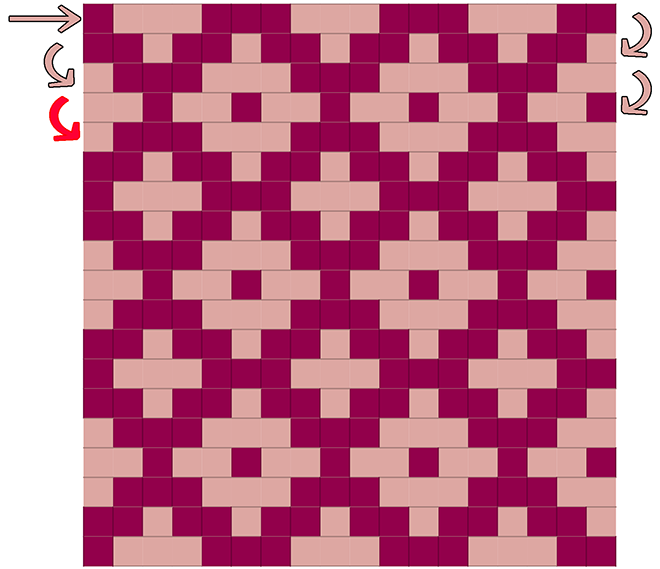

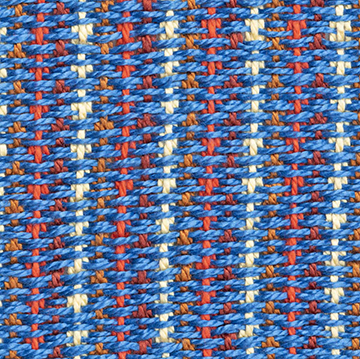

Below is the drawdown for the entire bumburet family which I first learned from Alice Schlein: bumburet, decape, thickset and velveret, in that order:

If you would like to find out more about these structures, they have entries in my on-line Pictionary©:

Here are the fabrics. Bumberet:

Ducape:

Thickset:

Velveret:

And then there is Greek Huck. Greek Huck? Yes, Greek Huck, but that’s another story….

Happy exploring pointed twills!

Marcy