| What is Droppdräll? |

Marcy Petrini

March, 2022

The short answer is:

Droppdräll is huck.

Droppdräll is NOT Bronson lace.

This blog is not so much about droppdräll as it is about how confusing weaving terminology can be, especially across different languages. But is also about how versatile structures can be.

In the January / February issue of Handwoven, Christine Jablonski wrote: “I inserted elements of a droppdräll draft into my log cabin threading.” Editor Susan Horton pointed out that the structure is no longer a log cabin, but a color and weave effect.

What is droppdräll? I asked myself.

From the draft of the structure and the photos of the lovely towels, I could tell that the element of droppdräll were the gold threads interspersed with the two colors of the original log cabin. But that didn’t really answer my question.

I looked up droppdräll in my Swedish weaving book but droppdräll wasn’t specifically explained. So, I turned to the web.

The first thing on my web search was a droppdräll towel by Adrianna Funk who said that “droppdräll is the Swedish term for Bronson Lace, applied here to create a whole lot of texture!”

I thought I had my answer until I scrolled down and found the drawdown for Funk’s droppdräll. It didn’t look like Bronson Lace.

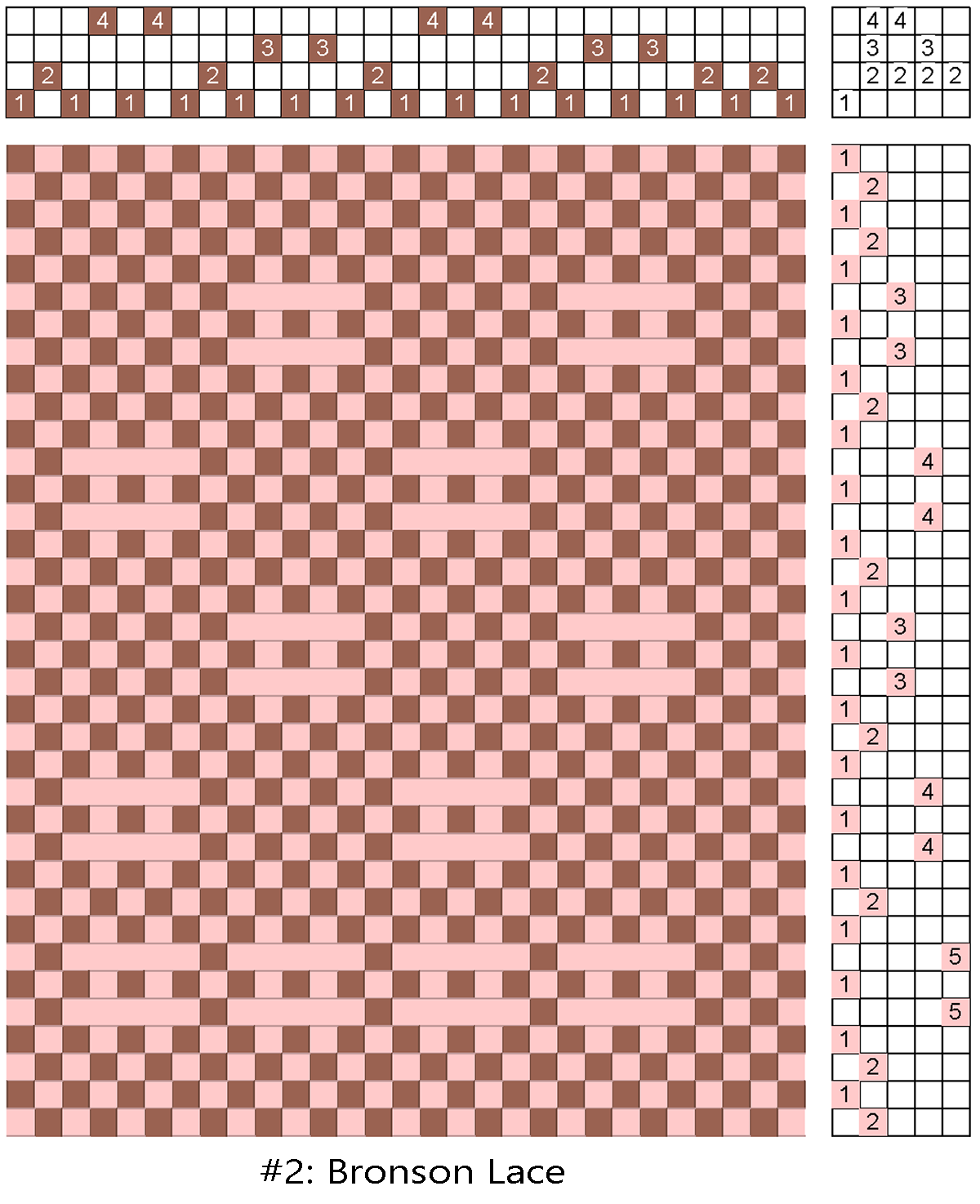

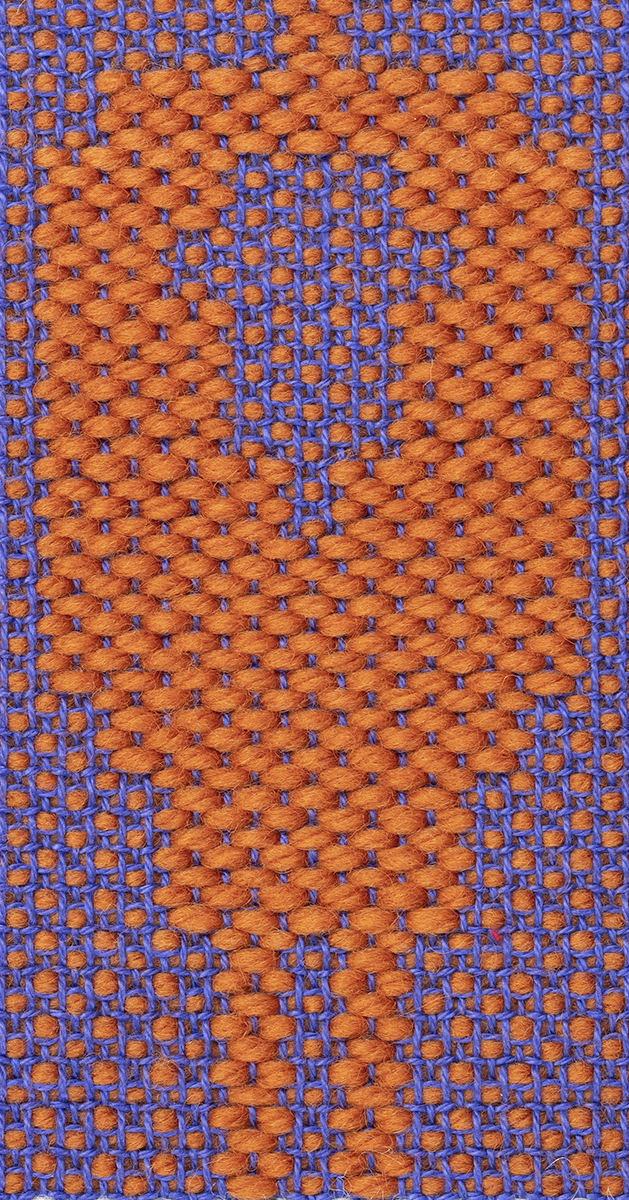

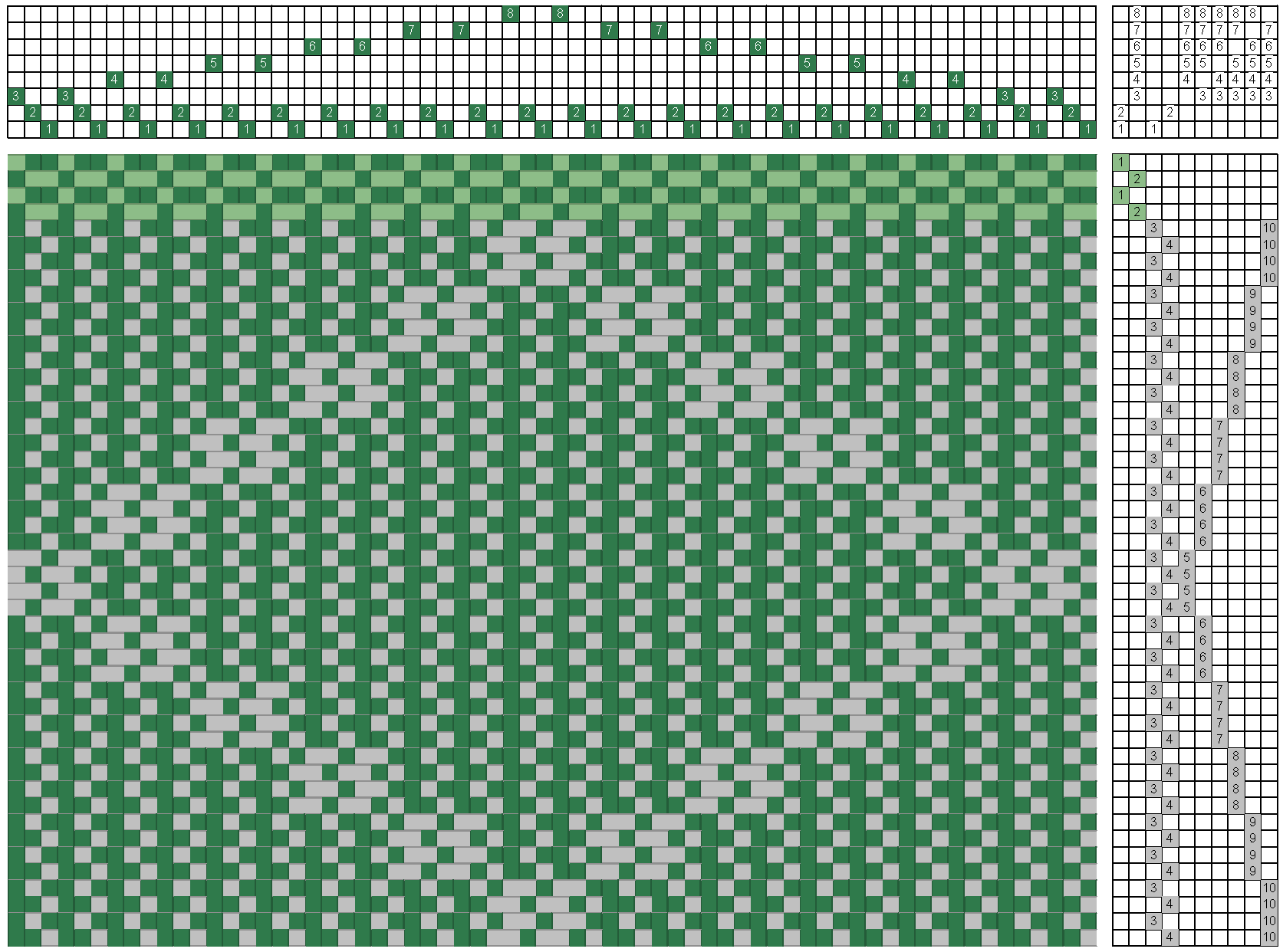

To better understand the structure, I copied the drawdown (rising shed), and color coded it to separate the blocks and the plain weave areas. Here it is:

The structure has floats as many lacey weaves do; it can be described as a rectangular float weave in Emory’s classification, but it does not look like the structure we generally associate with Bronson Lace, shown below in the rising shed drawdown:

Maybe it’s a modification of Bronson Lace, but if that’s the case, I should be able to modify it back to its original structure.

Looking at the Funk’s drawdown, we see that the double floats in the two blocks are the result of two shots on the same shed, as opposed to the usual Bronson Lace which has its floats in the two blocks separated by a tabby. This means that the underlying fabric of Bronson Lace is plain weave, while in Funk’s structure, when one block has floats, the other block has pseudo plain weave, or half basket weave.

But it is possible to have plain weave across the fabric in Funk’s example, so I should be able to place a tabby between the double shots to match Bronson Lace.

Here is my modification of Funk’s original draft:

It’s back to being a traditional lacey weave, but is it Bronson Lace?

Bronson Lace is a unit weave, the distinguishing characteristic of which is that blocks can be combined in the treadling. This is shown at the bottom of the drawdown of the classical Bronson Lace (drawdown #2). It is not possible to combine blocks in the treadling of the modification of Funk’s droppdräll (drawdown #3) because the two blocks use different tabbies.

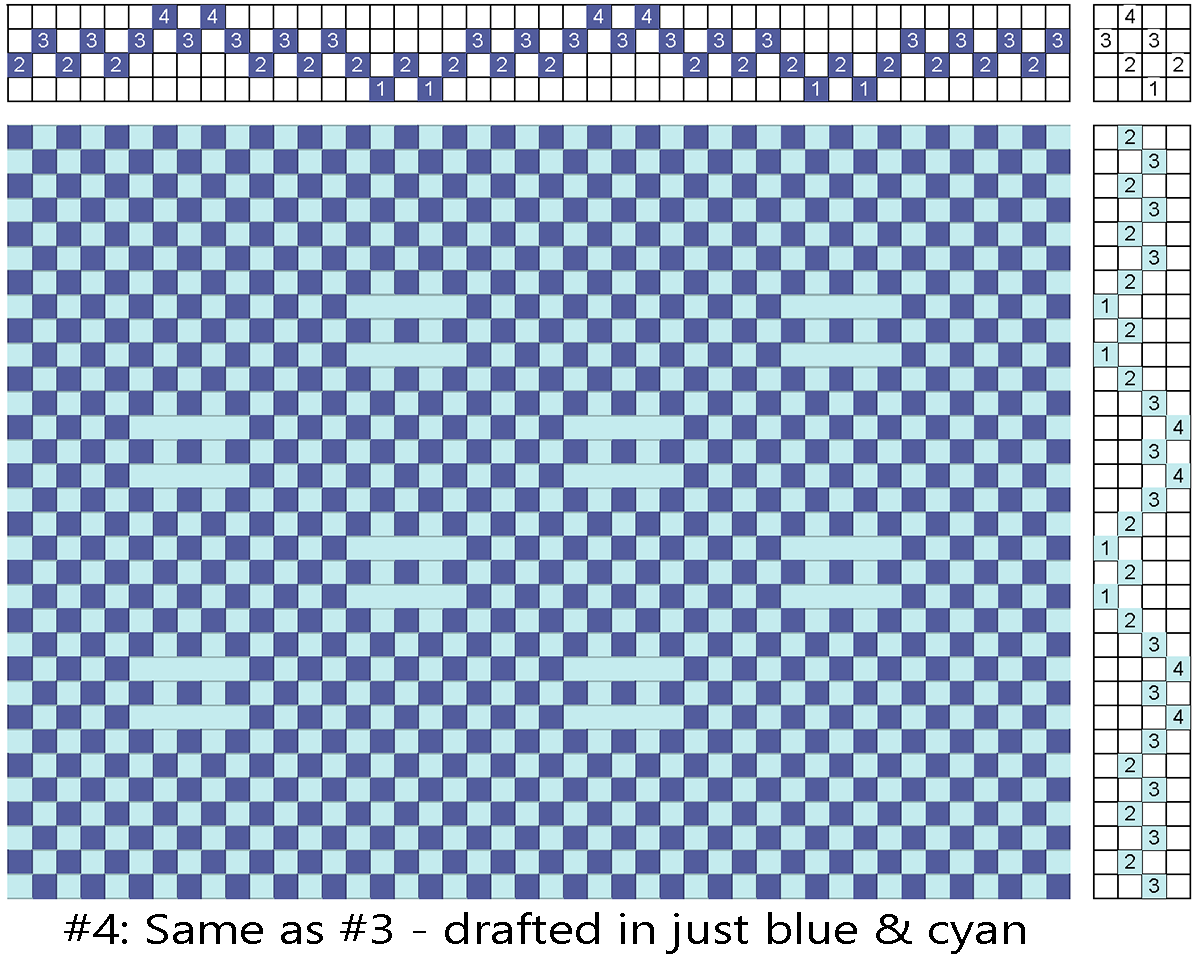

The color coding is great for allowing us to study the blocks, but it is confusing when looking at the drawdown to see the structure. Next is the same drawdown as above, with one color for the warp and one for the weft.

This looks like huck which is shown the next drawdown. While the threading and treadling are different, it is the fabric that defines a structure.

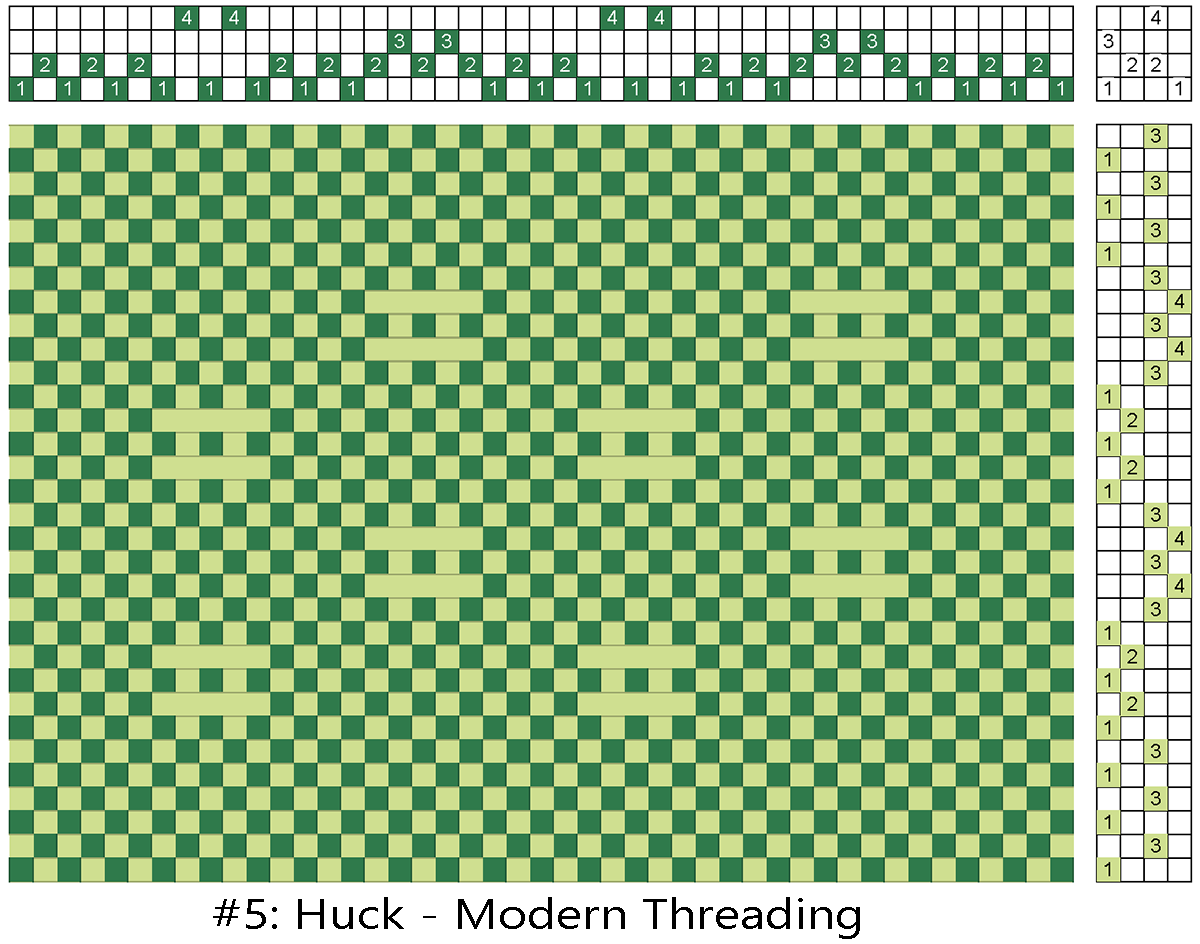

The drawdown for huck above shows the way that most recently huck is threaded; this makes it easier to add blocks with more shafts. In older books, however, we find the threading of huck as shown below:

So, what we have is three ways to thread huck. Funk’s original drawdown is a treadling variation of huck, interesting, but definitely not Bronson Lace.

While I was pondering this huck, my colleague Peggy Cole sent me a pdf of the Practical Weaving Suggestions One Color Upholstery Fabrics, Vol. 2-58, by Edna Olsen Healy and published by the Lily Mills Company, Shelby, N.C. The electronic version of the booklet is in the public domain and is available from the University of Arizona at this link:

https://www2.cs.arizona.edu/patterns/weaving/periodicals/pws_58_2.pdf

Samples E-1, F-1 and F-2 in the pamphlet are droppdräll, which the author says it’s “a little known Swedish technique.” The pictures of the fabric show a lacey structure. Time to investigate.

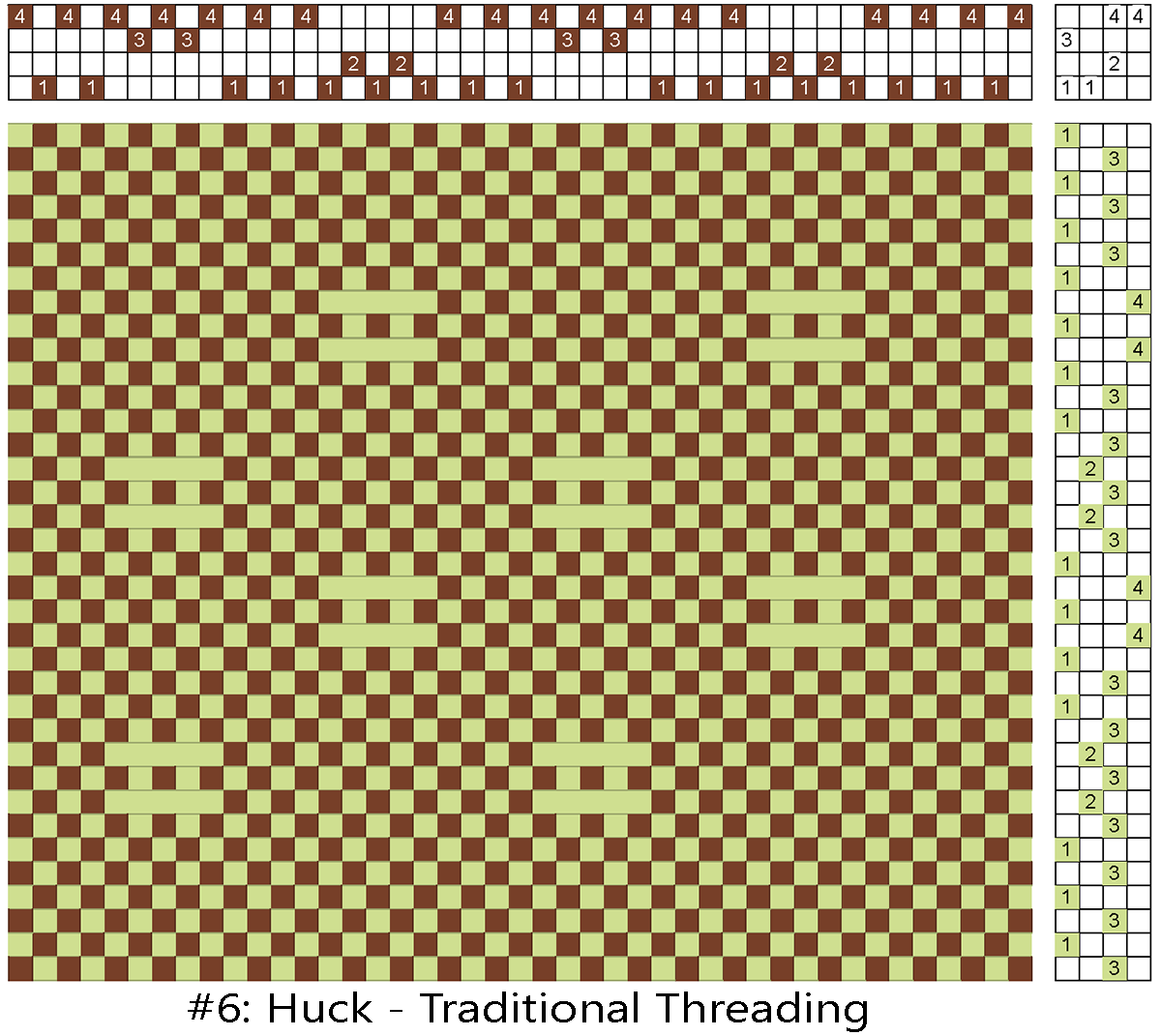

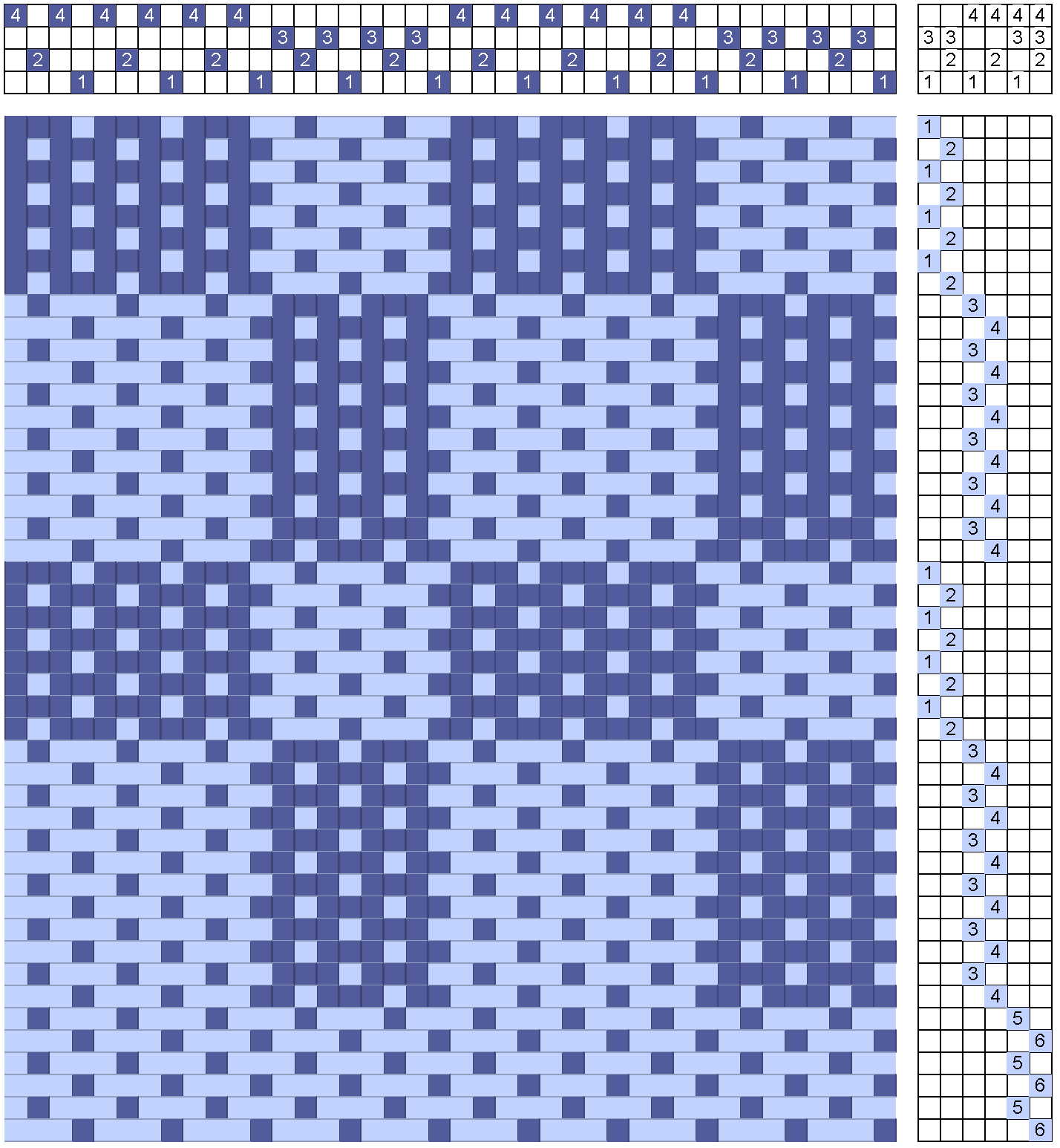

The first sample uses 6 shafts. The booklet is too old to have computerized drawdowns, but the treadling, and the tie-up appear in graphical form, and the treadling is listed as treadling steps. Thus, it is possible to create the drawdown and check it with the photo of the fabric. Here is the sinking shed drawdown for the first sample (as given in the directions):

The fabric in the booklet shows the first motif but there are directions for a square pattern block which I added at the bottom of the drawdown. The author says that the structure is usually woven as a lace weave, but it can be used for upholstery by using a closer sett.

The next sample in the Lily booklet is droppdräll on four shafts. Edna Olsen Healy says that she had never found a 4-shaft version, so she devised one, which I reproduced below, using her graphical threading and tie-up and her treadling steps. The drawdown is for a sinking shed as published.

This structure was used for two samples: one for a lacey fabric, the other for upholstery. In order to weave the sturdy fabric needed for upholstery, she used the treadling steps in the drawdown above alternating a fatter pattern thread (treadles 1, 2) with the tabby weft, same size as the warp (treadles 3, 4). The fabric does indeed appear to be sturdy for upholstery.

The motif on 4 shafts (drawdown #8) resembles the square pattern block at the bottom of the 6 shaft drawdown (#7). I thought it should be possible to make it look more like the diamond, the first motif, by simply re-arranging the treadling of the blocks. Here is that option:

With the drawdowns complete is time to analyze them.

Looking at the threading, this, too, is a modification of huck. In drawdown #6 of the huck, we see that the two block threadings are: 1, 2, 1, 2, 1 and 4, 3, 4, 3, 4. Here Edna Olsen Healy has reduced the classical 5-thread block of huck to 4 threads. The tie-up is different because my tie-up is for rising shed, to match Funk’s drawdown (drawdown #1), while Healy used a sinking shed (drawdown #8). But here is the drawdown for a rising shed:

As I was working through these possibilities, a book called To Weave the Swedish Way was about to be published. Reserving the book pre-publication allowed me to get it here rather quickly. The book is great for beginning weavers, with basic information and lots of projects to weave. But in the midst of it, there is droppdräll, or huckaback. The authors are Adrianna Funk and Miriam Parkman. Funk is the same author whose information started this search, but now she is no longer calling it Bronson Lace, but huck! Maybe Ms. Parkman is a better translator.

But the drawdown for this huck is basically the same as the first drawdown in this blog, from Funk’s website, with double shots to make the double floats. The amount of plain weave between the blocks is the only difference in the book version.

So, according to Funk and Parkman, droppdräll is huck, albeit modified, and “Lily droppdräll” another modification. I had come full circle.

There must be a revival of Swedish weaving, because I read a review in the current issue of Shuttle Spindle & Dyepot of a book called The Weaving Handbook by Åsa Pärson and Amica Sunderström. I am grateful for the review and Tracy Kaestner who reviewed it because, from the title, I would not have guessed that the book is on Swedish weaving. But it is! Droppdräll is huck, no question about it.

The Weaving Handbook is wonderful for the details. It explains briefly how floats are derived from plain weave, which is the way I like to think of lacey weaves. Furthermore, there are lots of treadling variations, some on four, others on more shafts. As we know, the difference between huck and huck lace blurs with more shafts, but I like to think of huck lace as a treadling variation of huck.

Did I waste my time by re-discovering the wheel? I don’t think so, although my search started because of a misnomer. But in thinking this through, I have re-learned to be careful of what names people give to weaves. All of the structures discussed here can be classified as Emory’s float weaves derived from plain weave, also called rectangular float weaves: two interlacing elements forming rectangular blocks. I will be presenting a seminar at Convergence™ discussing rectangular float weaves.

I learned lots about droppdräll / huck variations which I plan to weave. I am hoping to post the samples in a future blog. And that will include not only all of those above, but this one which piqued my curiosity, using three shafts:

Try droppdräll, I mean huck!

If you want to learn more, come to my seminar at Convergence®, I would love to see you there!

Happy weaving!

Marcy

| One More Tied Unit Weave |

Marcy Petrini

February, 2022

I will be presenting a seminar titled “An Eight-Shaft Primer of Tied Unit Weaves” at Convergence®, so I have been weaving tied unit weave samples.

My original intent for proposing the seminar was to review what I knew and to learn a bit more. But I am finding that the more I learn, the more I discover there is to learn.

First, I wove summer and winter on 8-shafts with its many treadling options. Here is a sheep from Strickler’s book A Weaver’s Book of 8-Shaft Patterns from the Friends of Handwoven (pg. 148):

Next I went back to old favorites, for example Tied Lithuanian; then I tried structures I hadn’t woven before, for example half-satin.

Soon I realized how unhelpful those names are in understanding the structure. While Tied Lithuanian and Tied Latvian – different treadlings on the same threading – are at least descriptive of where they originated, half-satin is a deceptive name: satin is a simple weave by Emery’s classification, simple meaning one warp and one weft. tied unit weaves are compound structures, one warp, two wefts, specifically supplementary weaves, since the additional weft is not needed for the integrity of the cloth.

Some supplementary weft weaves, for example overshot, are inherently different from tied unit weaves; to differentiate them, Donna Sullivan in her book Summer and Winter, A Weave for All Seasons, uses the term supplementary weft patterning for tied unit weaves, because they generally form a characteristic stippled pattern, as seen in the sheep.

With this name confusion, I went back to Donna Sullivan’s classification which can be used for any number of shafts; using summer and winter as an example, here is how tied unit weaves can be described; unfortunately with more shafts, the nomenclature is not always unique:

|

Nomenclature |

Explanation |

Summer and Winter |

|

Single, double, etc. |

Number of pattern shafts per block |

One shaft of pattern per block, 3 for A, 4 for B, 5 for C, etc. |

|

# Tie shafts |

Number of shafts for the tie down threads |

Shafts 1 & 2 |

|

Paired or unpaired |

Whether the ties are next to each other (paired) or not |

Shafts 1 & 2 are separated by the pattern shaft |

|

Ratio |

Tie-down threads to pattern threads within a block |

For each tie down thread, there is a pattern thread |

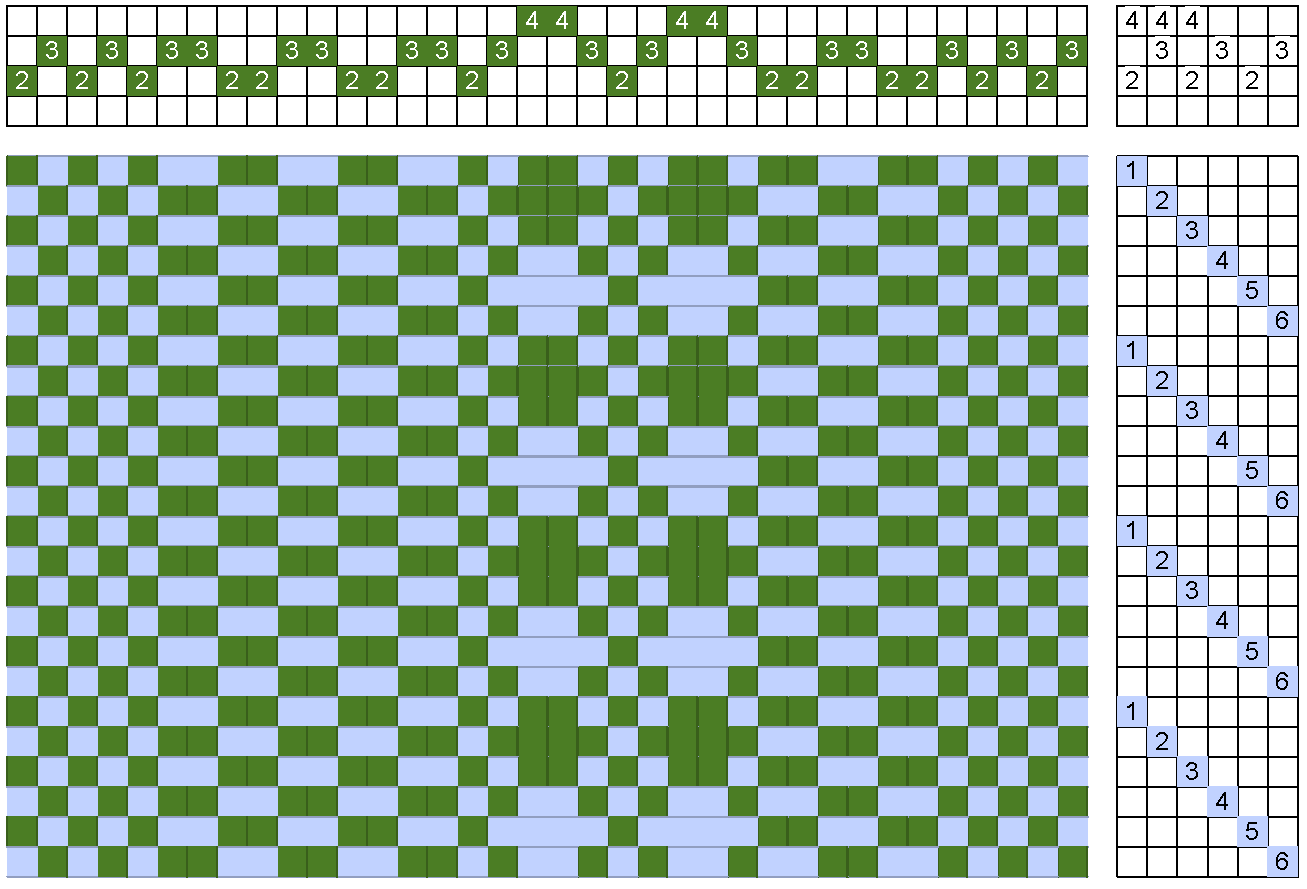

Thus, summer and winter is a single, two tie, unpaired with a ratio of 1:1 structure. We can abbreviate to single, unpaired two-tie, 1:1.

Below is the drawdown, using sinking shed and showing only the pattern weft. In weaving we alternate each pattern shot with a plain weave shot, treadled 1 & 2 vs. 2 & 4. The reason for using a sinking shed is because we think of “weaving a block” as covering it with weft. When the warp lowers, the weft floats over it, making the connection between shafts and blocks easier to see.

The drawdown shows the features of tied unit weaves. The first distinguishing characteristics is that the threading of each block is fixed, the ties limit the floats, so blocks can be repeated adjacently. In the above draft for summer and winter, block A is repeated 2 times, block B 3 times. When we look at the drawdown, the blocks are seamless, just different in size, but the weft floats are never longer than over three warp ends.

The second distinguishing characteristic, this shared with all unit weaves, is that blocks can be treadled together. This is shown at the bottom of the drawdown, but it is also seen in the sheep motif. This characteristic of combining blocks in treadling is a powerful design option, especially when we expand to more shafts, as seen in the sheep.

Bronson Lace is a unit weave, but not tied, even though at first glance, shaft 1, shared with all blocks, makes it appear that it is a tie. The drawdown below shows that shaft 1 acts as a tabby and the floats in the blocks are delimited by shaft 2, the other tabby.

Blocks can be combined in the treadling, shown at the bottom of the drawdown. But to repeat blocks they have to be separated by shaft 2, while in summer and winter the blocks are adjacent.

Once I clarified the classification, I decided to look at the possibilities in a methodical way and see which structures I had not woven yet.

Summer and winter – single, unpaired two-tie, 1:1 – is the simplest of unit weaves and can be woven on four shafts. If we look at the nomenclature, we know we couldn’t have blocks with less than a single shaft! But from the above discussion about the difference between tied unit weaves and unit weaves in general, we know that we need at least two ties for a structure to have fixed blocks.

The next logical step to me was to change the other parameter: single, with two paired ties. I didn’t find that option where I looked, certainly not an exhaustive search, but it is easy enough to determine what it should be.

The ratio is 1 pattern thread for 2 two ties, so the structure is: single, two-ties, paired, 2:1 ratio.

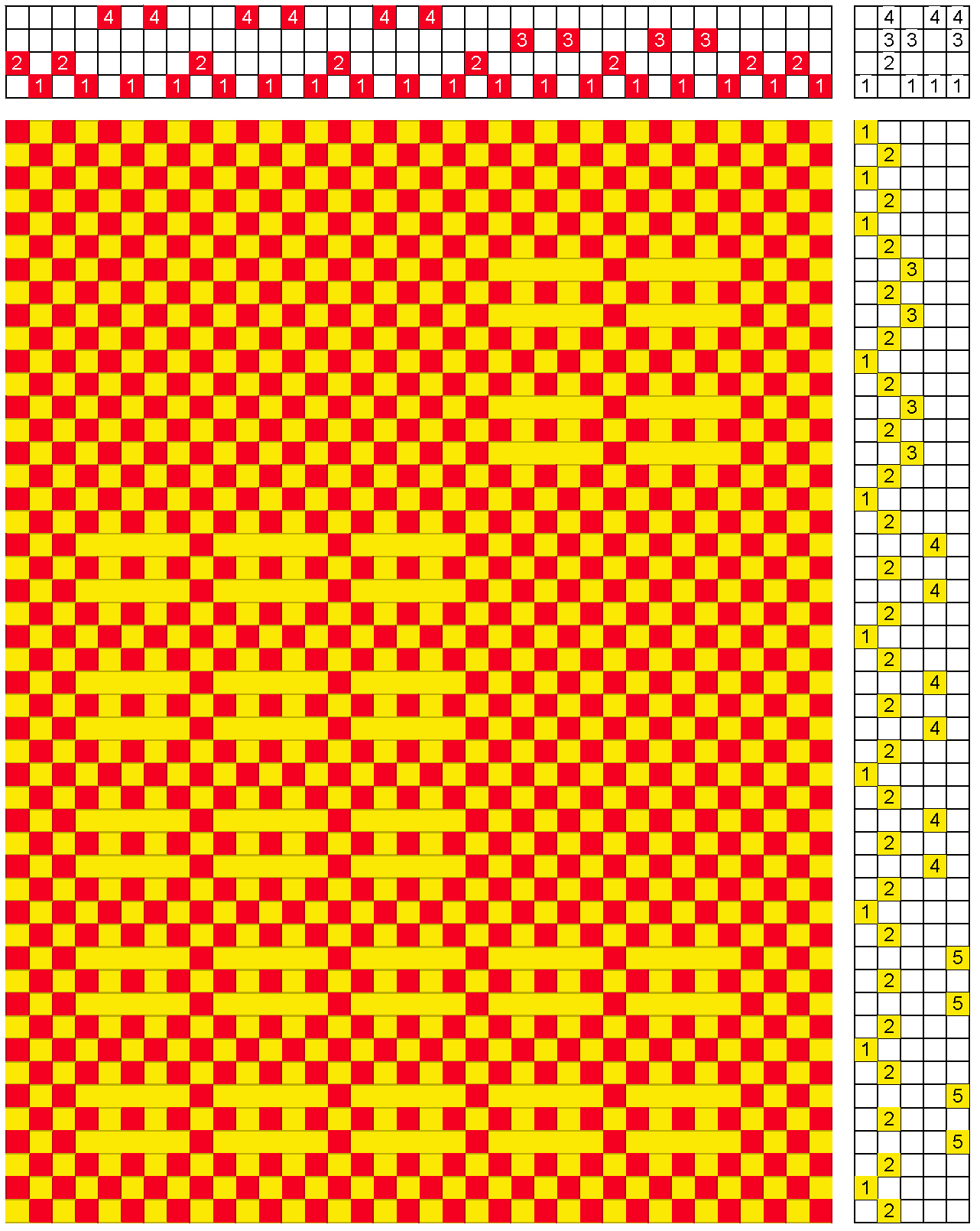

Because the block is small, I doubled each one for my sample; I threaded the 6 blocks in pointed order and wove diamonds as shown in the drawdown.

For the treadling, I added a pattern shaft to each tie and treadled the blocks in that order, as shown in the draft. This is a common way to weave tied unit weaves.

As with all other tied weaves, a ground thread alternates with the pattern thread. The top of the drawdown shows the treadling steps for the ground, which is not plain weave, but a pseudo basket weave. This is not unusual, other tied weaves have grounds that are not tabby.

Here is the front of the sample, green warp and ground weft, off-white pattern weft:

And here is the back:

As written in the draft, the treadling requires 14 treadles, but I wove it on a loom with 10 treadles using two feet. The ground required 2 treadles, the tie down shafts 2 more, and the pattern blocks 6. My loom is also a rising shed, so in order to weave each block, I had to raise all other shafts, that is, to weave block A which uses shaft 3 in the threading, I had to lift all pattern shafts but 3. Below is the actual drawdown for my sample.

The possibilities for tie weaves are many: more than one pattern shaft, more than two ties, and once we increase either number, there are a variety of ways that the shafts can be arranged. For example, the tie unit weave called Bergman –single, three tie, unpaired, 1:1 – uses 3 ties, arranged in a 3-shaft birds’s eye twill, while another by the same nomenclature, uses a pointed twill.

If you want to learn more, come to my seminar at Convergence®, I would love to see you there!

Happy weaving!

Marcy

| A Shaded Twill |

| — and — |

| The Year Ahead |

Marcy Petrini

January, 2022

At the beginning of the year, I like to take some time to recap my weaving for the past year and to look forward to the coming year.

There are two reasons as to why I like to look back: I am always surprised at how much I have actually woven; weaving is just part of my fiber work, I also write and teach, on zoom during this pandemic time. So, seeing the list of pieces and samples that were finished during the year gives me a sense of accomplishment.

The other reason is to ask myself where am I headed with this work: am I happy to stay the course? Do I need to find a new direction?

With Convergence® on the horizon, this past year has been full of sampling for the seminars I will be presenting. I like to either weave new samples or expand the selection; in 2021 I have been sampling rectangular float weaves, including unit weaves, and tied-unit weaves, a total of 10 sampler warps.

I wove 5 pieces that were part of my COVID-19 series all of which I have documented in blogs on this website and, together with the 2019 COVID-19 pieces, were assembled into a booklet which we mailed to family and friends in lieu of a holiday card in December 2021; below is the cover of the booklet.

A few more things were woven: 3 shawls on the AVL and 2 sets of napkins because my husband often remarked that he felt like the shoemaker’s child – no shoes. We now have some nice and serviceable napkins.

With this overview, it’s time to think ahead. I am in the process of organizing the samples to see what else I may want to weave for the seminars and the monographs that I will have for Convergence®. Below is one of the tied-unit weaves samples, single, 3 unpaired ties, 1:1 ratio (a single pattern shaft per block, 3 shafts for ties which alternate with the pattern shaft resulting in a 1:1 ratio of pattern threads to tie threads). Two more samples are in the works already and another in the planning stage. I am sure there will be more. I will re-assess that part of my weaving after the conference.

I haven’t decided about the COVID-19 series. Frankly, I thought we would have moved on from COVID-19 by now. After the delta scarf, described in the December 2021 blog, I was thinking of weaving something for the “new normal” as I described in the December blog. I hadn’t even gone past that thought that omicron arrived….. I decided to take a break from COVID-19 weaving and think about what next.

I needed some comfort weaving, but with a bit of a challenge to keep things interesting: I decided that I would weave a twill I have never woven before and use yarn from my stash, at least one of which had to be a yarn I had never used before.

The yarn was easy. When HGA was closing its on-line store, they had a few skeins of a variety of Convergence® yarns that they were selling deeply discounted, so I bought the very last remanence. I received several skeins of my favorites – and 4 skeins of 10/2 rose Tencel®. There is nothing wrong with the rose color skeins, but as a child I had a rose color dress made of silk taffeta that I just hated, the rustling drove me crazy. So, the rose color skeins have languished in my stash for a few years. That yarn had to be used, even if in small amounts. Here is the yarn wound into a ball, ready for use!

Meanwhile, I was leafing through Davison’s book for twills. The “shaded twill” on page 51 caught my attention. The drawdown below shows that it is composed of stripes of a simple undulating twill and basket weave. I could thread the basket weave section with the rose Tencel®.

I planned on 5 sections of the undulating twill separated by 4 sections of the basket weave. I looked at a few 20/2 silk yarns for the twill, since 10/2 Tencel® and 20/2 silk is a combination I have often used successfully. I settled for a yellow green for the outside twill sections, a bluish green for the next 2 sections, and a variegated silk for the middle section. I sett the entire warp at 24 epi and I adjusted the number of ends so that I could have an 8” scarf. Floating selvages were not needed since the pattern started and ended with a straight will.

Next the weft. I thought a green silk may work, but the pattern disappeared; I tried yellow, but it overwhelmed the scarf – a little yellow goes a long way, but an entire weft is too much. I settled on a cinnamon color 10/2 Tencel® also from the Convergence® batch, which I had used before. The After Image of the cinnamon yarn is a pale bluish green, making the blue-green warp more noticeable.

The complete scarf is the first project off any of my looms this year:

And here is a close up. The undulating portion is a bit unstable, so a warp sett of 28 epi would probably have been better, but the scarf is usable.

It’s time to go back to sampling…..

Have a healthy and safe 2022 and I do hope to see you at Convergence®!

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

Delta: Covid Strikes Back

Marcy Petrini

December, 2021

As I write this, it’s mid-December 2021, and in Mississippi we are in the second wave of the Covid-19 Delta variant, with the variant Omicron on the horizon.

But the scarf that I wove for the Delta was during the first wave, starting in August and continuing through September. Just as we were enjoying our newfound cautious freedom, the pandemic, instead of retreating, was ramping up again.

The virus mutates and the more viruses there are around, the more the chance of mutations.

And with a high percentage of unvaccinated, there are a lot of viruses around.

Sadly, vaccinated people with confounding medical conditions are dying.

But most of the cases and deaths occur in the unvaccinated; they chose “freedom” over their fellow men. The virus has freedom to choose too, and it strikes back with Delta.

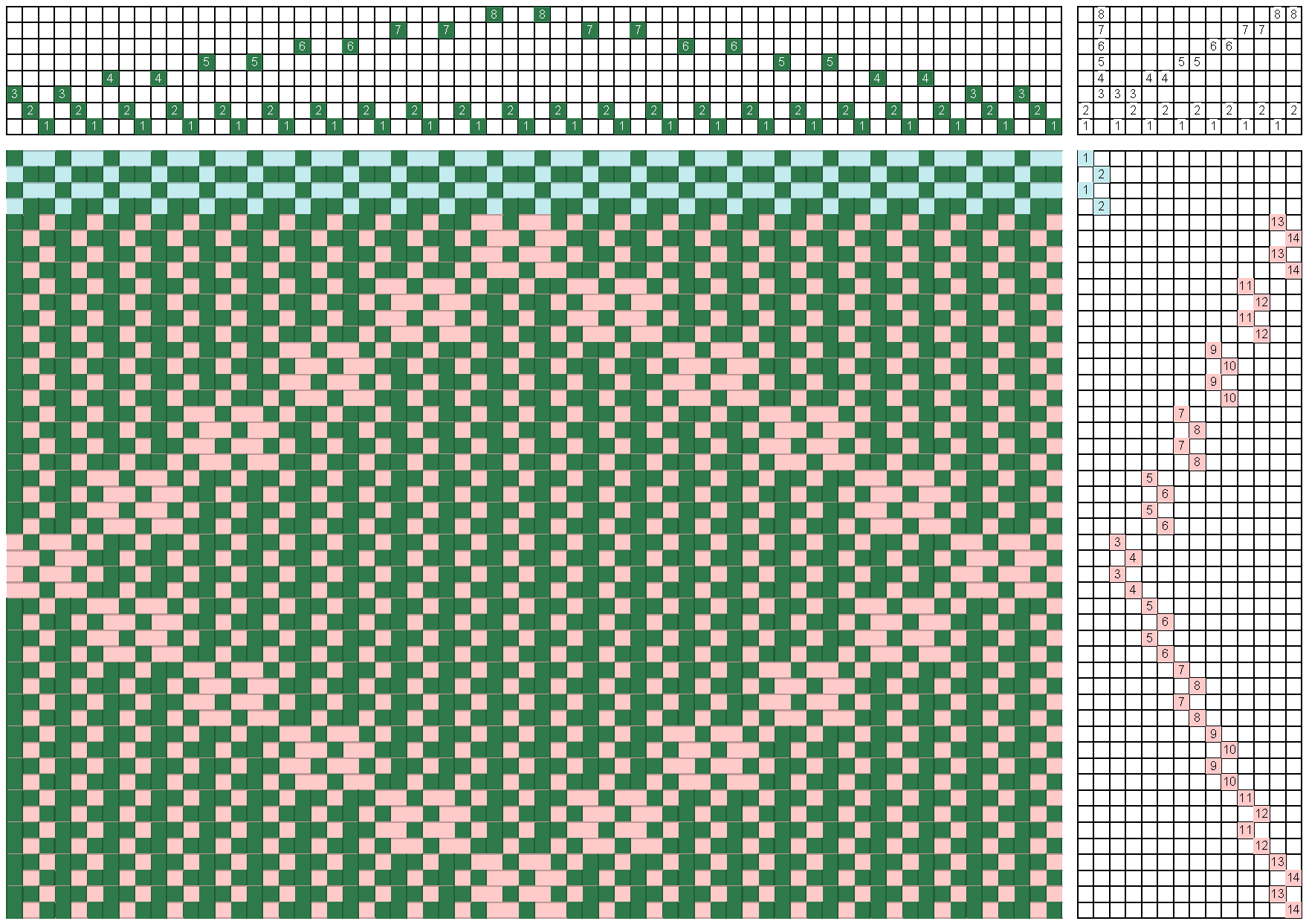

The scarf was a way for me to deal with the frustration. Here is a close up:

As I was thinking about the scarf, I knew I would choose red for the Delta; when I saw the first drawing of the virus back in early 2020, it was depicted in red, and since then, when I think of the virus, “I see red.”

Because vaccination is so helpful, I didn’t want the warp to be totally black; breakthrough infections, as they are called, are usually a mild disease. So, I wanted a warp ranging from off white to black, maybe different size stripes.

A more distinct Delta could be obtained with more shafts, but my 4-shaft floor loom was ready for a warp, so the design would have to be on 4 shafts. I always say that limitations enhance creativity. A pointed twill threading was the obvious choice. To make the pointed twill stand out, I would weave bands of the twill in red, alternating with a neutral color, maybe one of the warp yarns.

To make the individual deltas separate, I abbreviated the treadling and separated each row of twill with plain weave. As I was working with the drawdown, this thought occurred to me: “with this pandemic, we don’t know if we are coming or going (coming down or going up in cases)”. So, I decided that the half the Deltas would be up, the other half down. I tried a few combinations, and finally settled on four rows on one direction, and four in the other direction, with plain weave separating the sections as well as the rows.

Here is the final drawdown:

I removed the usual 1 & 2 treadling step to separate the delta motifs; three shots of plain weave separate the 4 rows of pointed twill, nine separate the rows of pointed twill motifs from the 4 rows of reverse pointed twill motifs.

Meanwhile I was working on my yarns. A beautiful hand painted silk, black and greys from Jems Luxe Fibers, approximately 1,000 yards/lb. was perfect for the warp and for the non-red sections weft of the scarf. For the red I found in my stash a Henceforth Yarns 100% silk 4/2 spun, dyed red by Neal Howard.

While the yarns are a bit heavier than may be ideal for a scarf, because it is 100% silk, the scarf does drape well.

As I was finishing the scarf, as the case numbers were finally decreasing again, I read about an interview with Dr. Robert Wachter, the chair of the medicine department at the University of California, San Francisco who suggested that for people with a booster shot, this may be the “new normal”: masks, social distancing from people whom you don’t know are vaccinated, and other similar precautions. I could live with the “new normal”, all of my friends are vaccinated. Maybe my next weaving should be the “new normal”. Of course, experts caution, all bets are off if we get a new variant….

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

Take Me Out to the Ball Game!

Marcy Petrini

November, 2021

In 2020 Major League Baseball cancelled all Minor League games. But in 2021 our M-Braves were back! The Mississippi Braves are the AA Affiliate of the Atlanta Braves.

Being outdoors, baseball games were an activity approved for controlling the virus. Alone or with friends, we were regulars at Trustmark Park.

Even though the team didn’t play its best early on, it was wonderful being back; after all, the grass is greener, the sun shines brighter and the beer tastes better at the ballpark! But the M-Braves improved through the season and won the AA Southern League Championship.

Going to the ballgames, I would sing to my husband:

Take Me Out to the Ball Game!

Imitating Carly Simon, but not very well.

One day, as we were driving to the ballpark, I thought: I should celebrate by weaving a scarf!

As I talked about in my October blog, I had been thinking about linen weaves in Davison’s book, and I thought that the one in the canvas weave chapter would be the perfect structure to depict a baseball. However, I had to modify the draft because I didn’t want the canvas blocks to be throughout the fabric or even staggered in columns.

Meanwhile I was thinking of colors: green for the grass and white stripes for the ball. I could change the drawdown to get a mixture of plain weave and pseudo-basket weave for texture, as ballparks usually have a variety of grass cuts Here is the drawdown:

Looking at it, I realized that I could use the middle thread on a shaft 2 for a red stripe. Because there is a single thread, the stripe wouldn’t be solid, but alternating warp and weft – perfect for the stitching on the baseball!

But a green fabric with white stripes, even with the red stitching, wasn’t very exciting. I started thinking about the colors of ballpark – infield is brown!

As a baseball field, the scarf didn’t have to be symmetrical. As I was working with the proportions of the colors and the structures, I had an idea of where to place the white stripes:

a foul ball

a bunt

an infield hit

and a line drive!

I used 20/2 silk for the green, brown and red; to make the white stand out more, I used 8/2 silk.

Finally, it was time to weave; using the green of the warp for weft made the fabric somewhat flat. I tried a variety of green yarns, and found that a 10/2 Tencel®, color sage, worked well.

Here is the Take Me Out to the Ball Game scarf and close-up.

By the time the scarf was done, the season was over. But that’s OK, I wouldn’t be wearing a silk scarf to a ballgame with 100 degrees weather!

Happy Weaving!

Marcy