|

Roc Day and Cotton! |

Marcy Petrini

January, 2026

After one year hiatus, it was great to be back at Roc Day. The River Road Fiber Guild hosted in Plaquemine, LA and it was wonderful – good friends, good food and fun activities. Chair Charlene Bishop, Stephanie Keenan, Margaret Garnier and the rest of their “crew” organized everything to perfection. They even cooked for us!

Our guild, the Chimneyville Weavers and Spinners Guild had several attendees. We had a “de-stash” table to raise some money for our educational activities and participated in demonstrations as shown below.

I was asked by Charlene to talk a bit about the Roc Day history. I had written an article about it with emphasis on Mississippi since it was for the digital Mississippi Folk Life publication, but it describes what Roc Day is and some of its origins.

There were door prizes. One of the participants won a lovely box of various cottons to spin: Pima, Acala, brown and green. She came to me to ask me how they were different. I could answer some of her questions, but I couldn’t remember all the details. I told her that I had written a one - page flyer “a couple of years ago” for inclusion in some of the Roc Day goodie bags and I promised I would go home, look for it and send it.

And I did. But the “couple of years ago” were actually 12 since the last revision!

I remembered that Ply magazine recently published an issue on plant fibers which included an article on cotton by Jill Duarte. There wasn’t much new in the article about the cotton plants from what I had written in the flyer, but it made me focus on clarifying my descriptions. I added the article in the bibliography and when I emailed the cotton flyer to my new spinning friend I recommended the article to her so she could learn more about spinning cotton.

Happy Weaving and Spinning in 2026!

Marcy

|

(Almost) Always Mix, Never Worry |

Marcy Petrini

December, 2025

“Always mix, never worry” is my motto. I weave a few scarves for our co-op a year and I generally use at least two types of yarns, one for the warp, another for the weft, although sometimes one or the other or both are also mixed. Below is a scarf with a warp of Italian cotton ribbon and a thin weft of 72% kid mohair and 38% silk.

I use nice and sometimes unusual yarns, ones that I have on hand, to keep the cost low and the price for the customers reasonable. Right now, on the loom, getting ready for our Oxford, MS, festival, I have a warp of 80% silk and 20% lavender from https://www.wearwithalltextile.com/ and a weft of mohair and wool blend.

BUT – and here is the big BUT – when I mix, I am familiar with each of the yarns. I have used them before, or if they are new to me, I generally sample them to get to know their characteristics before incorporating them into a project.

My winter weaving class at the Bill Waller Craft Center (https://www.mscrafts.org/) will be starting next week and the subject is for students to weave any item with a fiber they have never used. My suggestion is that they use the same fiber for the yarns for warp and weft. That’s because when using a fiber for the first time, no matter how much you may read about them, you have to learn about them by doing.

The same it’s true for spinning. Once familiar with a fiber, spinners blend to obtain some of the characteristics of each fiber, to make the blend more affordable, or to make it easier to spin.

It’s not surprising that the “Shave ‘em to Save ‘em” initiative of the Livestock Conservancy (https://livestockconservancy.org/get-involved/shave-em-to-save-em/) requests that “show and tell” on their Facebook feed not be of a mixed fiber. The spun yarns and finished products should be one of the sheep breeds on the endangered list not mixed with other breeds or other fibers. To learn about these breeds that we may lose if not protected means that we use them singly first and foremost.

Recently at our guild meeting a member suggested to another spinner that she blend silk with wool to make it easier to spin. The spinner had never spun silk before, and the silks were those below: Bombyx, Muga, Eri, and Peduncle Tasar.

I reacted rather negatively to the suggestion. Even if someone has spun the usual bombyx, these silks are so different that it would be impossible to learn about them by combining them with anything or even each other.

These silks have come to the market rather recently and I fear that they are going to become scarce because of tariffs. So, it behooves us to learn about them while we can.

Mix and not worry, in weaving or spinning but only if you are intimately familiar with the fiber.

Happy Weaving and Spinning in 2026!

Marcy

|

Crepes! |

Marcy Petrini

November, 2025

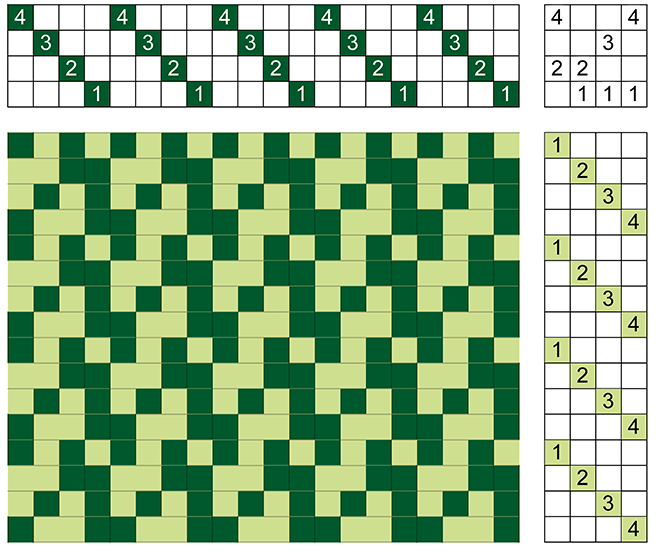

In the October blog, I described my confusion about pebble weave and pebble twill. They are both twills by Emery classification: a progressive successions of floats in diagonal alignments. The pebble twill has a unique threading with a straight draw treadling. The pebble weave uses a straight twill threading with unique treadling steps.

Thus, we can think of the pebble weave as a treadling method for a straight twill threading. Treadling methods are treadling sequences applied to one or more threadings, often twills. This is in contrast to a “twill” which has a threading and its own treadling, the “tromp as writ” treadling.

I also mentioned that it is possible to weave the pebble weave with a treadling that is similar to that of the crepe weave.

That got me thinking: here is another confusing pair, the crepe weave and the crepe twill. While the crepe twill is indeed a twill, the crepe weave doesn’t have the progressive succession of floats that we need for a twill.

The drawdown of the crepe weave below shows the “on opposite”: treadling: 1 & 2 is followed by its opposite 3 & 4; 2 & 4 is followed by its opposite 1 & 3. Thus, this is also a treadling method applied to a straight draw.

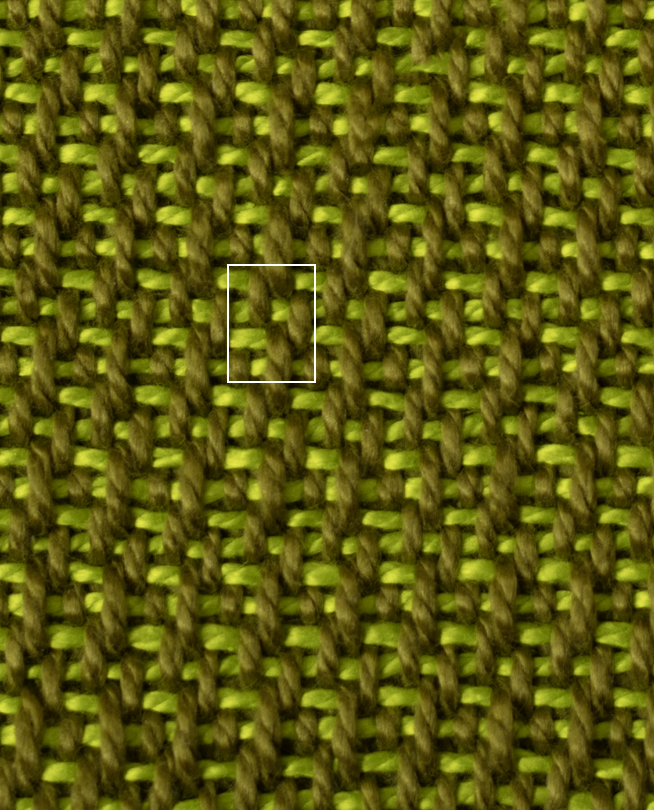

The fabric is textured, as seen below. The name comes from fabric made with crepe yarns which the crepe weave tries to imitate.

Crepe yarns are highly twisted and when used in a plain weave warp with alternating S and Z twist yarns, they produce a textured fabric, according to spinning guru Mable Ross.

In contrast, the crepe twill has an interesting threading with 16-thread repeats. In the drawdown below the first repeat is shown in a lighter color to clarify it.

The threading is reminiscent of a tied-unit weave; the first eight threads are the same as the threading of the first two blocks of summer and winter. In the second set of eight threads, the “tie” on shaft 1 pairs with each “pattern shaft”, 3 and 4, followed by the ”tie” on shaft 2 again followed by the “pattern shafts”. The treadling is a straight draw.

This, too, forms a textured fabric, shown below. The first part of the cloth has a different color warp in parallel to the drawdown.

Weaving has been evolving for hundreds of years, in different parts of the world with sparse communication in the past. It’s not surprising that similar names have been applied to different weaving structures.

Happy weaving!

Marcy

|

Pebbles! |

Marcy Petrini

October, 2025

A few years back Susan Foulkes used a pebble weave for one of her projects published in Handwoven. In skimming through the article, I vaguely remembered the pebble weave, and I decided it should be something to look up and study. I put “Pebble” on my to-do list.

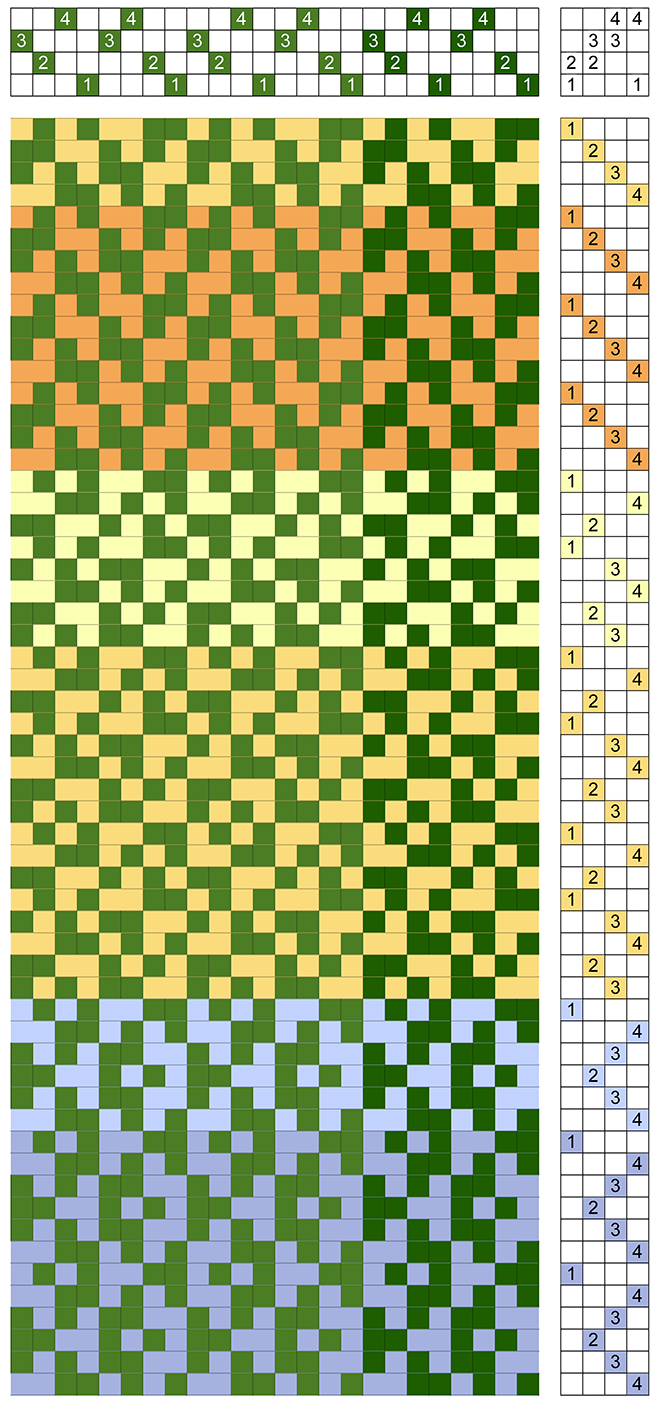

Eventually I arrived at the “pebble” entry on the list, and I looked up pebble twill in Davison’s A Handweaver’s Pattern Book. She has three treadlings shown in the drawdown below.

In the drawdown, the first repeat of the threading and the first repeat of each treadling are shown in a different shade to clarify them.

The pebble twill has a very clever broken twill threading; each repeat is eight threads. For the first four, we take the straight twill threading and break it by switching 3 and 4 and obtain: 1, 2, 4, 3, a common way to break a twill. For the second four threads, we take the straight twill threading and move shaft 4 before 2, 3 which results in: 1, 4, 2, 3, not as common, but another way to break a twill.

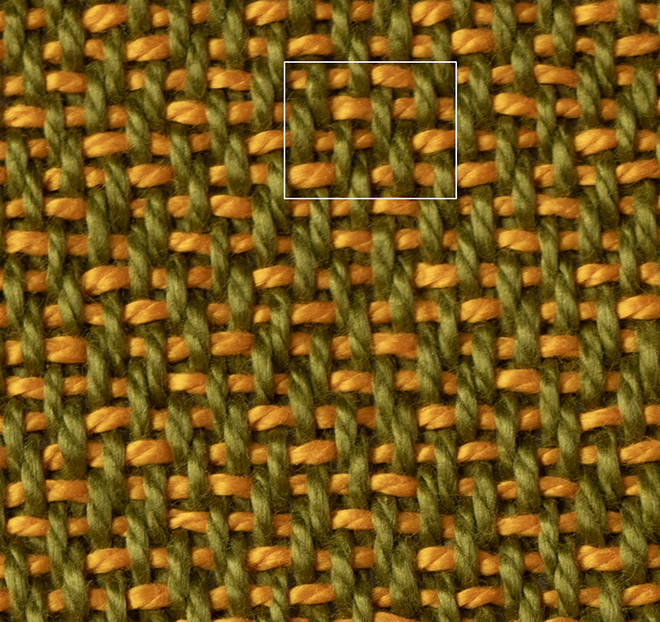

Below is fabric sample for the first treadling. A single repeat in the sample is marked by a square to highlight it, since it is really hard to detect it.

This is what I like about this twill: the repeat cannot be determined easily because the seemingly randomness causes the eye to jump around and the light to reflect in different directions. This is more effective and more interesting than the usual broken twill (see the Pictionary entry for Broken Twill.).

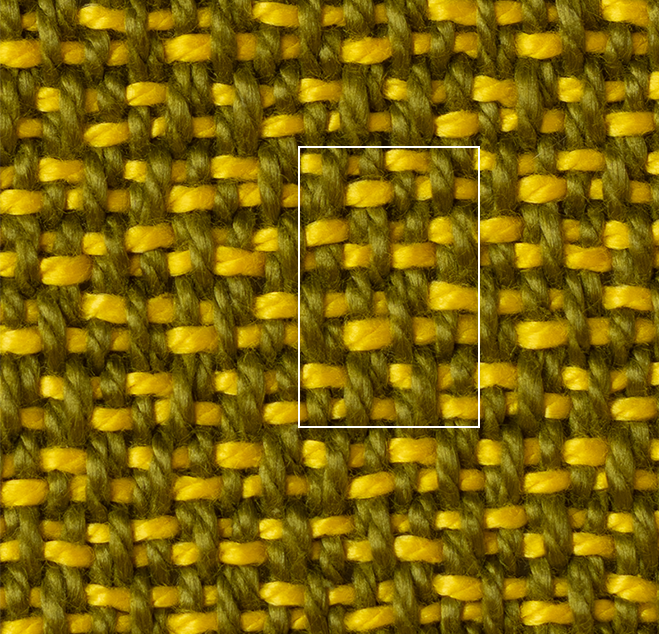

Below are the other two treadlings that are found in Davison’s book, also shown in the drawdown.

Interesting variations but not as easy to weave unless we re-tie the treadles.

At some point, I realized that Susan Foulkes had called her pattern “pebble weave”, but I just thought they were two names for the same structure as often happens in weaving.

However, this is not the case. The pebble weave is, indeed, a twill by Emery classification, but not the same twill as the “pebble twill.” We usually don’t refer to a single twill as a weave, but it’s not unusual and in this case it may help differentiate between the two.

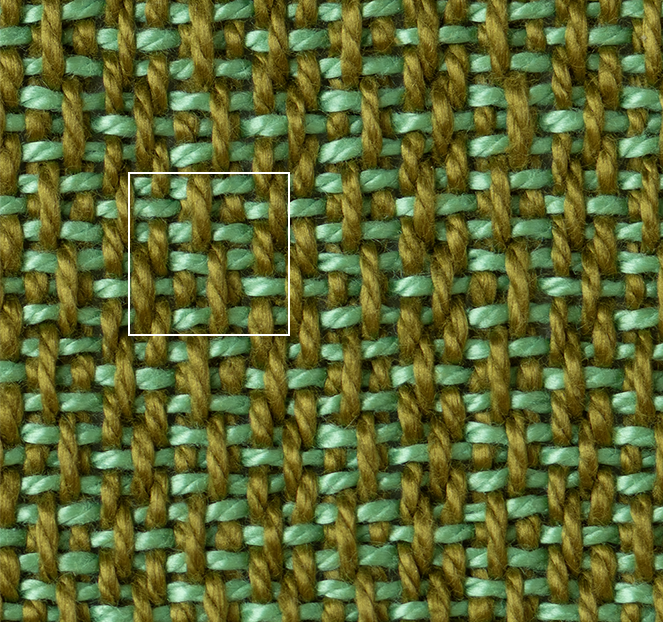

Below is the drawdown of the pebble weave. It is a straight threading with a treadling that uses the plain weave picks and two of the traditional picks from the straight draw: 1 & 2 and 1 & 4. This combination also results in a broken twill.

Below is the fabric sample, with the square highlighting one repeat of the twill. Davison has another treadling for the pebble weave, similar to the crepe weave (also a twill), using pairs of opposite treadles in the tie-up (See the Crepe Weave Pictionary entry).

The dots that appear in the fabrics may be giving the two twills their pebble names, more obvious in the drawdown than the fabric, and actually, more obvious in the pebble weave than in the pebble twill.

Lots of ways to break a twill and make a fabric with good drape but not an obvious motif.

Happy weaving!

Marcy

|

Red and Green |

Marcy Petrini

September, 2025

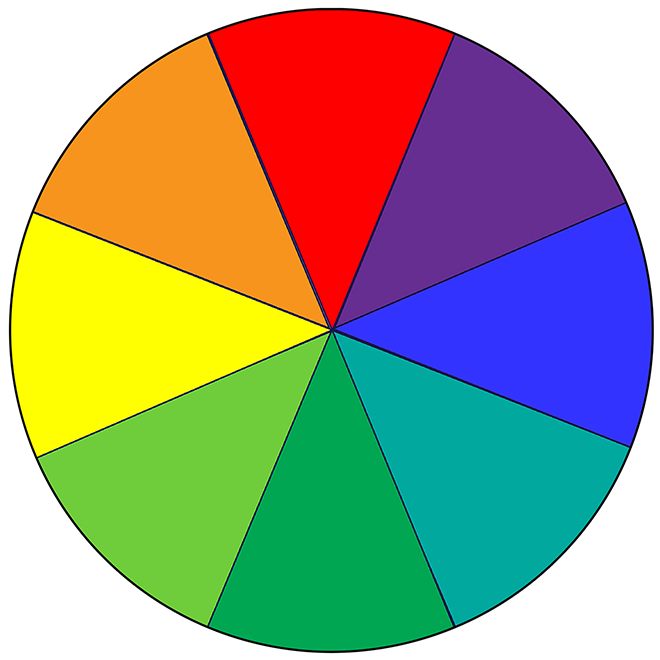

In the June 2025 blog I described the opponent color wheel, as shown below again:

This results from the way our visual system perceives colors:

Red ↔ Green Spectrum

Blue ↔ Yellow Spectrum

Light ↔ Dark Continuum

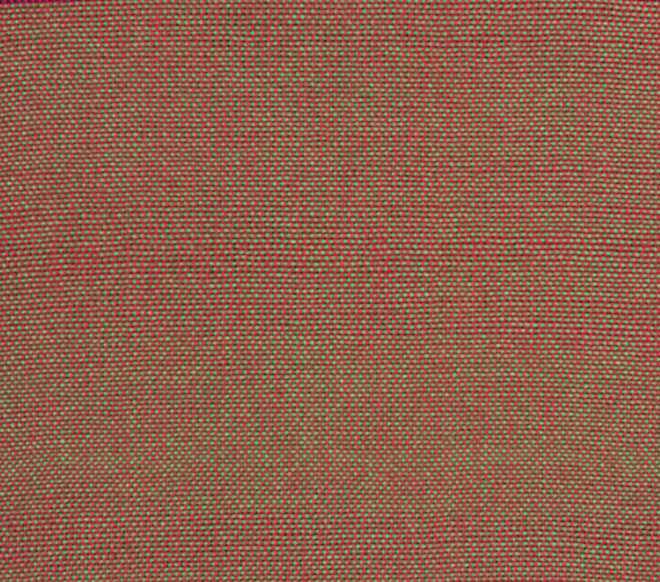

In the July 2025 blog, I showed a plain weave fabric with the two opponent colors, red and green, which became dull from the optical blending.

However, opponent colors do not always look dull toogether. Our visual system responds to the circumstances in which it sees colors.

First, our brain detects a shape, then it fills it with color.

If the brain can’t detect the contour of the shape – the individual threads or motifs – the colors will blend. In July 2025 we saw that blending can result in pleasing combinations or in dull fabrics, depending on the colors.

If the contour of the shape can be detected, then the brain looks at the colors while our eyes jerk from spot to spot, called a saccade. If the colors happen to be opponent, for example red and green the fabric will be shimmering.

Compare the next two samples: the first is the one from the July 2025 blog: red warp with green weft in plain weave, resulting in a rather dull optical blending.

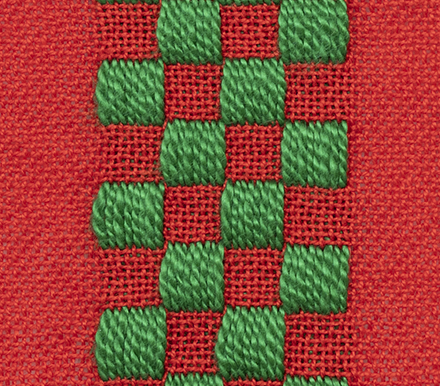

The second sample is also a red warp and a green weft but woven with a twill. There are enough treads together to provide a good saccade: the fabric shimmers.

An even more shimmering fabric results from the sample below which was woven with a red ground warp, a green supplementary warp and a red weft, same as the warp.

The large areas of green on top of the red makes the blocks seem to float.

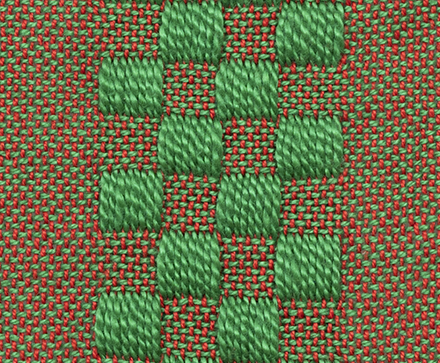

In contrast, below is a sample using the same red warp and green supplementary warp; the weft, however, is green, the same as the supplementary wasp.

There are a two visual effects here. One is the optical blending of the red and green plain weave, resulting in a dull fabric as we saw in the first example.

However, it is hard to believe that the supplementary warp in the sample below is the same as that of the sample above! The contour detection between the optical blended background and the green blocks is blunted, so the saccade doesn’t result in a vibrant outcome. The block edges are less clear and the green is not shimmering.

Understanding these opponent colors allows us to manipulate our yarns for our projects. A holiday runner in red and green? Try a bold twill or blocks, but no plain weave in red and green.

Happy weaving!

Marcy