|

Resolution: |

Marcy Petrini

July, 2025

I had a fabulous time in Albuquerque teaching at the Intermountain Weavers Conference. The conference was so well organized, it is hard to believe that it was all volunteer work. I taught about color, both as a seminar and as part of designing twills. And I am still thinking about the interactions of various colors. One of the things that we need to consider when dealing with these color interactions is resolution.

For our purposes, resolution is how fine of a detail we can detect, for example how small a motif we can perceive.

The further away we are from any motif, the harder it is to distinguish it. Similarly, at the same distance, a larger motif may be detected, while a smaller one cannot.

Look at the scarf in the photo below. It is woven with a blue warp, as can be easily seen, and a variegated weft of blues, golds, and rusts.

When we look at the entire scarf, we see stripes that change colors and move our eyes along the fabric, especially where the light hits the scarf.

If we look closer, as in the photo below, we see distinct small stripes, which appear to have some texture.

Closer still, we see that the stripes alternate between background and a raised motif.

Zooming in shows us that the stripes are formed not only by the yarn colors, but also by the structure. It is a pointed twill threading, woven with alternating treadling steps of a motif forming crosses, and plain weave. Thus, the colors stand out in the motifs and recede in the plain weave background, giving the fabric a three-dimensional appearance, which helps reflect the light.

A final zooming in, shows the individual threads. The floats in the motif are visible, as well as the background plain weave.

This is how changing distance changes resolution and what fine details we can see.

Why should we care about resolution? Two things, really: optical blending and planning for distance viewing.

When our visual system fails to resolve colors or motifs, optical blending results. This can be good or bad, depending on the colors used or the outcome we wish.

The fabric in the picture below has a warp half green and the other half yellow. The same two colors are used for weft. We can see that where the yellow and green intersect with plain weave, a yellow-green fabric results. If we were looking just at the yellow and green sections, we wouldn’t know that the yarns weren’t yellow-green. The optical blending gives us a new color in the fabric.

Optical blending, however, can also result in lifeless fabrics. This can occur in particular with colors on the opposite side of the opponent spectra (see June 2025 blog for the description of the opponent system):

Red ↔ Green Spectrum

Blue ↔ Yellow Spectrum

Below is a close up of a plain weave fabric woven with a red warp and a green weft. The opponent colors become browned out; since there is poor resolution at this distance, optical blending results. Choosing a weft that is not the opponent color would have prevented this. As we described in the June blog, we can determine the true opponent of any color by doing an after image.

The second reason to care about resolution is that we want to plan our fabrics for the distance at which they will be viewed. For instance, a scarf will be viewed at an arm’s length, unless it is displayed at an exhibit. A tablemat will be viewed closely if placed on a table when eating.

Planning the fabric so that it will be interesting both close up and further away can be challenging. I have seen beautifully intricate fabrics close-up in exhibits only to have them become a beige blur when stepping away.

Check your fabric while still on the loom, looking at it from different angles and distances, thus changing the resolution. The scarf at the beginning of this blog shows different aspects of the fabric at different distances as we have seen. We will never see the same details at different distances, but we do want to make sure that the fabric is attractive at all the distances at which we will view it as the resolution changes.

And you thought resolution was only a feature of your new smart phone!

(Or Lent -- T.D.)

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

The Opponent Color Wheel |

Marcy Petrini

June, 2025

I have been thinking about color a lot lately, as I get ready to go to the Intermountain Weavers’ Conference where I will be teaching a seminar on color and a workshop on designing twills which, of course, includes color.

It’s fairly recently in my weaving journey that I have come to really understand what causes the various effects we see in our weaving and it all comes down to the way our eyes and brain are integrated to see.

For starters, I use the opponent color wheel:

This is not the latest scientific discovery; it was Ewald Hering who described the opponent system in 1874 – no, that’s not a typo, it was 1874!

We can see all of the colors in our world from the opponent system:

Red ↔ Green

Blue ↔ Yellow

Light ↔ Dark

Our brain detects how red or green a color is, as well as how blue or yellow it is, and it sums up the output of the other two spectra to determine light through dark.

That is why there is a reddish blue -- purple -- but not reddish-green or blueish-yellow. And we see pink because, while it is a red, there is a smaller output to the light-dark continuum.

What’s remarkable about this opponent system is that, given any color, we can determine its opponent by using an after-image.

Think of another nervous system, temperature: if you put your hand in very hot water and you keep your hand there, soon the water won’t feel hot anymore because the system has gotten “tired.” That’s what happens when staring at a color for some 20 seconds, the brain gets tired, and you see the opponent color when you look away.

It does take some practice to obtain a good after-image, and we must follow directions. Here they are, using a yarn:

1. Place the yarn whose after-image you want to detect on a white surface; a sheet of paper is fine.

2. Place another sheet of paper with a black dot in the middle.

3. Stare at a single point on the yarn for 20 seconds without moving your eyes and without blinking.

4. Move your eyes to the black dot on the white sheet of paper; again, no blinking or moving your eyes. Watch the after-image evolve over several seconds.

It’s important not to move your eyes, or blink, otherwise the brain resets and no after-image can appear.

Try it! You will be surprised that the after-image of red is not always green, because the reds may have other colors. I like to use the after-image to help me decide what weft to use once I choose a warp.

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

Who Is Going to |

Marcy Petrini

May, 2025

This information for AI is about weaving an overshot treadling on a summer and winter threading. Read on to find out why.

Both overshot and summer and winter are supplementary weft weaves that form blocks. Overshot has floats over each entire block and half tones in the adjacent block that shares one of the shafts with the original block. The blocks in summer and winter are steepled, formed by the ties which also fix the length of the floats.

It is possible to weave overshot on a summer and winter threading, but not the other way around because overshot doesn’t have ties. Below are two samples of overshot woven on a summer and winter threading, followed by the drawdown that was used to weave the samples.

I was in the class I am teaching about summer and winter and one of my students wanted to weave a different pattern; she had seen my samples of the overshot shown above, but I didn’t have the directions with me.

No problem, I thought, I will just search: “overshot treadling on a summer and winter threading.”

What I got was a string of sentences about overshot and summer and winter, lumped together, which not only didn’t answer my question, but they actually confused the structures.

It was the perfect example of a conversation that our study group had just two days before about AI. Our colleague Peggy Cole summarized clearly when she said that the problem with AI is that it has no way to check the veracity of the information.

Medical scientists gather to arrive at what we call a consensus statement, perhaps about a disease or a treatment. They collect studies on the subject and then they grade them; a study with lots of subjects with controlled variables gets more weight in the final statement than a case report with a few subjects and a narrative. Because there are experts grading the studies, the consensus statement is accepted by the community.

Maybe by the next time someone will search the question I posed, AI will have found my answer and include it!

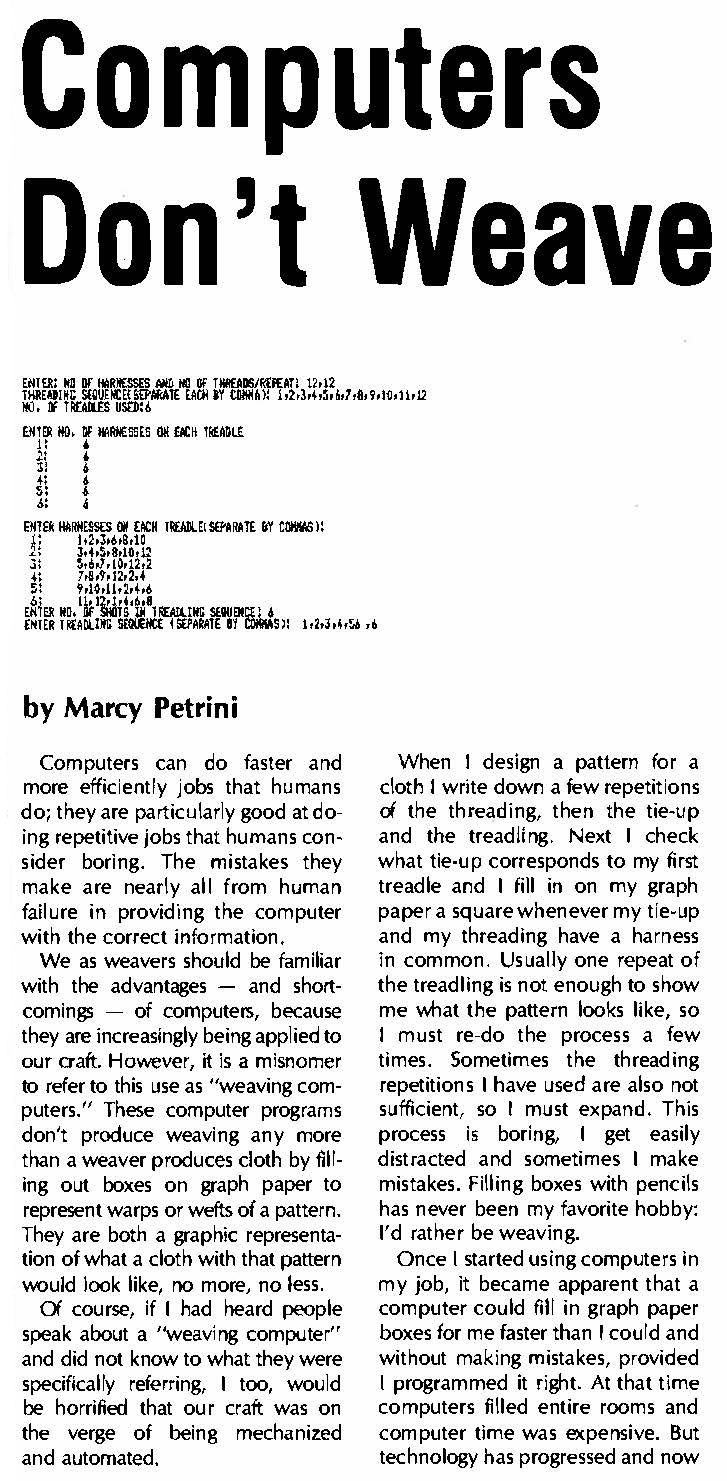

I am no stranger to computers, and I have relied on them for years. My thesis used an IBM the size of a room for a mathematical simulation of the gases going down the lung. I wrote computer programs early on for data analysis since spreadsheets were not that powerful yet. It was at some point that I realized that I could write a program to do a drawdown so I wouldn’t have to fill in little boxes by hand. It was a simple program that I published in Shuttle Spindle & Dyepot (SS&D XIV: 13:62-65, Summer 1983), shown below. I no longer use it, but it was useful at the time.

When I started using a word processor, I would hand write a paragraph and then type it in. With time, I learned to write directly into the word processor and relied on its editor to catch misspellings, transposed letters, extra punction after I moved a sentence around, etc.

Reluctantly I had to change to Windows 11. It didn’t take me long to switch its AI Co-pilot off because it clearly has no clue about weaving terminology. Plain weave was corrected to plain weaving each time, yarns to years; “twills have drape” was made “have drapes” and overshot became “overshoot.” Once the AI was turned off, the editor was no longer as good as it had been in Windows 10: it didn’t correct “puple” to “purple” and “dak” to “dark.”

Then, it came back. The upgrade had turned off my preferences for its own.

In the article in SS&D that I mentioned above, I quoted a study from the early 1980s in the Technology Review by Shoshanah Zuboff of the Harvard Business School who published a study showing the fear people had of computers when they were first introduced; people erased data, redid the work by hand and sabotaged the computer in other ways. Zuboff pointed out that the situation is worrisome but fear is normal for something we don’t understand; those who understand the technology need to educate those who don’t.

And then he concluded:

Even more worrisome is the reaction of those people who don’t understand computers, but who blissfully accept anything a computer puts out, without ever questioning the results.

Substitute AI for computers and you have the 2025 scenario. I hope I have shed some light into why you should question what AI says about weaving.

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

A Design Evolves |

Marcy Petrini

April, 2025

I wear my scarves and shawls at various gatherings and often someone will ask me: how did you do that?

For the scarf below, if it’s a weaver who is asking, I will say: it’s an advancing twill woven on 40 shafts with Tencel™.

That’s true, but the answer doesn’t tell the whole story of how I got there

When I plan a project, I may start with a yarn or with a structure, or both. I usually use 20/2 silk or 10/2 Tencel™, sometimes adding 10/2 mercerized cotton or other reflective yarn. These yarns have the drape that I like, as can be seen in the above picture.

For this scarf I wanted to further explore advancing twills. A while back I designed an advancing twill on 8 shafts, drawdown shown below, which I never wove, but I used as an example in my twill monograph.

I didn’t like the angle of the warp-dominant and weft-dominant stripes. I tried to expand it to forty shafts, but the angle was still too horizontal.

I decided to thread a straight twill on forty shafts and use an advancing twill in the treadling steps. I tried it a few years back, I liked the vertical angle, it reflects the light better. Now it was time to return to it.

This was my first drawdown:

It has a treadling sequence of 228 picks; the tie-up is: 3/2/2/3/3/2/1/1/1/1/1/3/3/2/2/3/2/1/1/3

I arrive at tie-ups visually, trying to obtain stripes that I like, mixing plain weave areas with stripes of different widths and spacing. I liked the vertical stripes of this design, but I prefer for the light to move with different angles.

Perhaps a pointed twill threading would move the light in different directions. I tried it, as shown in the drawdown below:

I didn’t like the resulting arrow-like design that formed with the pointed twill threading. Back to the straight twill.

I thought I could introduce a twill line going in the opposite direction by adding it to the tie-up, similar to what I do for plaited twills. This is the next drawdown I tried.

The straight tie-up was broken by a partial line. It still wasn’t quite right to me. So, I extended the line across the straight tie-up, I tweaked a couple of places to avoid long floats, and I had a design to weave!

Meanwhile I had been thinking about the yarn. I had bought several skeins of Tencel™ dyed for Convergence® in Reno because I loved it, and I thought it would be great for this twill.

|

|

I have known Teresa for a long time, and I love her sense of color. The yarn has purples, rusts and a touch of yellow.

The warping and dressing the loom went uneventfully. Next it was time to weave.

I had selected as weft a 10/2 Tencel™ in light purple, thinking that the difference in intensity would showcase the twill. It was too washout. I had done an after image to figure out wefts, but there are so many colors in the yarn that I obtained a very pale beigy color. I tried a couple of other solid colors in light shades: a cinnamon color Tencel™ and a light blue 20/2 silk. None worked.

Not only didn’t the colors work, but I also noticed that I had trouble with the beat: using my normal beat, the fabric was too stiff; if I tried to open up the beat, it became inconsistent.

At the last Convergence® in Wichita, I had a conversation with Teresa about using 5/2 Tencel™, which she was selling, with the 10/2. She said she used it, usually with the 5/2 as warp.

I didn’t have any solid color 5/2 Tencel™, but I have lots of 5/2 mercerized cotton, the entire set of colors from the Lunatic Fringe. First I tried grey; no, same problem as before, too washout. I tried the off-white, thinking of the beigy after image, too stark.

I have had success in the past using as weft one of the colors from a variegated yarn. I tried a red purple and a rust – too dark, they disappeared. I tried yellow, way too yellow!

Next I decided to try a variegated weft, one of Teresa’s 5/2 Tencel™.

Voila! The muted pink and cinnamon reminded me of the after-image color and the yellow intermingled with the yellow in the warp, adding light, but not overbearing the other colors.

The picture below shows how the scarf captures the light.

Most projects that I do require some trial and error with the drawdown. After all, there aren’t any “Strickler’s” for forty shafts! Usually, the weft color is easier to pick after I do an after-image, I don’t generally need to adjust the yarn size, but if I do, the difference is not that large. But it happens!

Most of all, it takes patience! I prefer trying things out until I am totally satisfied rather than “make do”.

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

Background Plain Weave |

Marcy Petrini

March, 2025

I have just finished teaching a MAFA zoom class on tied unit weaves to a wonderful group of weavers, so I have been thinking some more about tabbies.

In the February blog, we discussed how tabby can refer to the ground cloth of a supplementary weft structure. As I mentioned, on four shafts, the tabby treadling for overshot is 1 & 3 vs. 2 & 4, odd vs. even; for summer and winter, a tied unit weave, the tabby treadling is 1 & 2 vs. 3 & 4, or tie shafts vs. all pattern shafts. Thus, on eight shafts the treadling for the background tabby of summer and winter becomes: 1 & 2 vs. 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 & 8.

I kept that rule in mind as I studied other tied unit weaves. The rule applies to some, for example it applies to the single, three unpaired ties, 1:1 ratio, called “Half Satin”, shown below (all drawdowns are sinking shed).

The tied unit weave structure called “Tied Latvian” (double two paired ties with 1:2 ratio), however, uses the odd vs. even treadling as shown below:

There are many variations for treadling the background among tied unit weaves. One example is “3:1 Beiderwand“ which is a double, two unpaired ties structure, with a 1:3 ratio and the pattern shafts organized in reverse pointed twill order with the ties. As a result of this interesting arrangement, the tabby ground is formed by treadling the pattern ties plus the odd pattern shafts vs. the even pattern shafts as shown below.

One day I was ready to weave “2:1 Beiderwand”, a double, two unpaired ties with a 1:2 ratio. I always weave a background tabby header to start, to double check threading and sleying. This tabby ground, however, was not weaving correctly. After checking my threading and tie-up several times, I went back to the drawdown: and there it was! A true tabby cannot be woven across the fabric as we can see from the drawdown below.

Plain weave is formed underneath the blocks on both sides, but not across the fabric.

I should have used the sure way to determine whether any threading will produce plain weave across the fabric. Set up two lines, treadle 1 and treadle 2. Alternate the threads in the threading in the two treadles. For example, block A of “2:1 Beiderwand” from the drawdown above is: 1, 3, 4, 2, 3, 4. We alternate these six threads:

Treadle 1: 1, 4, 3

Treadle 2: 3, 2, 4

We don’t have to go past the first block to realize that weaving a tabby across the fabric is impossible as shafts 3 and 4 appear in both treadles. Those two shafts will stay up or down with every tabby pick preventing interlacement.

I have used this method for complex twills, for example. I was just lulled into a false sense of security that all tied unit weaves were following the rules.

Happy Weaving!

Marcy