|

More Blocks! |

Marcy Petrini

November, 2024

Just a few days away!

Because of this seminar, I have been thinking a lot about blocks…. More to come in December.

Meanwhile, here are two of my favorite blocks.

Can you believe that they were woven on the same threading? Do you know what they are?

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

Pointed Twill Blocks |

Marcy Petrini

October, 2024

After working through the tie-up and treadling steps for two twill blocks, I decided to use the warp still on the loom for some more experimenting. I wrote about these two twills block, false satin and turned twills, in the August and September blogs.

Looking at the twill block chapter in Strickler’s book, I was struck by how many of the blocks had treadlings that didn’t produce blocks, rather stripes. Others are intricate blocks, and some others are color and weave effect. They are all very interesting, but I wanted to go back to basics.

I thought I would try the next logical step, the pointed twill.

Strickler describes the threading process for twill blocks as using two repeats of a four-shaft twill, first on shafts 1 through 4, then on shafts 5 through 8. I decided to try that with the same tie-up as the turned twill blocks and a “tromp-as-writ” treadling.

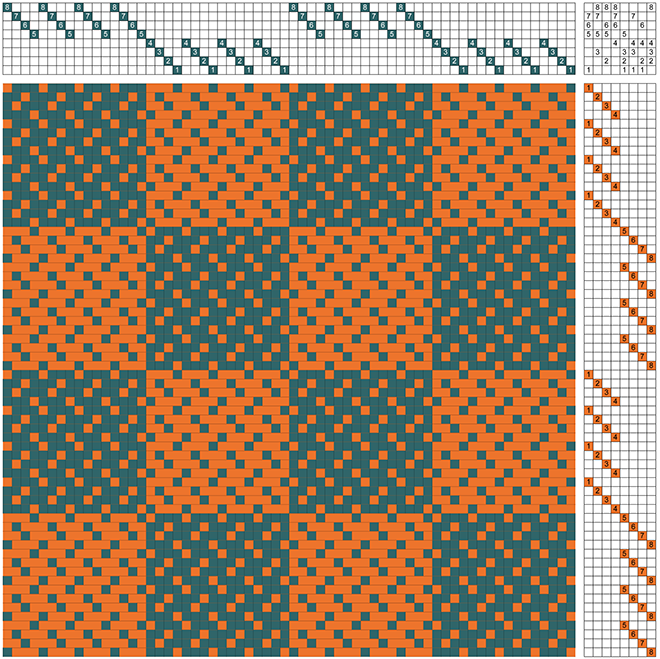

Here is the starting drawdown.

I made two decisions. The first is that I didn’t balance the threading because I wanted to maintain plain weave across the width of the fabric, as visible from the drawdown. That is not necessary and starting with a balanced threading for the two repeats on the two sets of shafts would result in different motifs.

My second decision was to start the treadling steps as “tromp as writ” but balanced, because I wanted the top and bottom of the blocks to be mirror images.

When I design motifs as I did here, I may change the threading or the treadling steps. The latter may be changed in the tie-up or in the sequence of activating the treadles. In my case, I threaded the loom first, so my only choice was to change the motif looks by changing the treadling steps.

I noticed that there were several places where the motifs were not symmetrical within the block. These are circled below in the partial drawdown of the right corner.

I looked at each one of the places where the motifs were not symmetrical left to right. For each, I looked at which shaft on which treadle was causing the asymmetry or which shaft added to a treadle would result in symmetry.

For example, looking at the top right of the warp-faced block on shafts 5 through 8 (circled above), I saw that shaft 5 on treadle 2 was causing that right corner not to be matched to the left corner. Removing shaft 5 from treadle 2 solved the asymmetry.

There were three other places that I changed: a) add shaft 1 to treadle 3; b) remove shaft 1 from treadle 7; c) add shaft 5 to treadle 7.

The two tie-ups are below for comparison, with the changes highlighted. The original on the left, the final on the right.

|

|

Below is the final drawdown

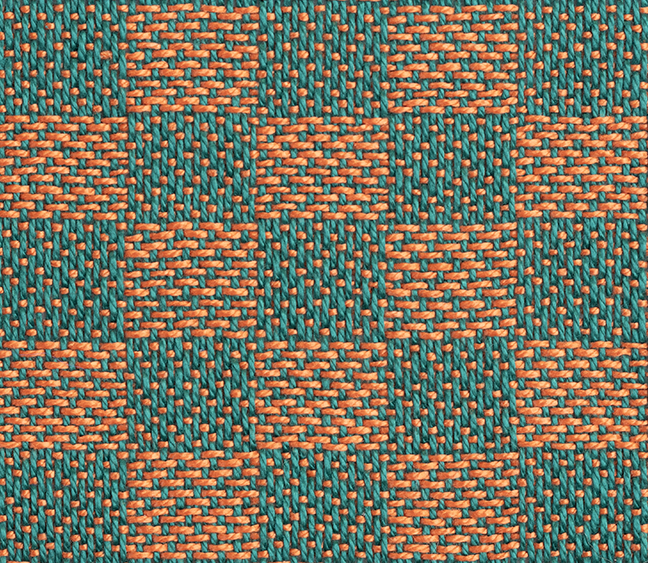

Here are the samples, front and back woven from the drawdown above.

|

|

I would like to clarify the treadling nomenclature. It you look at the treadling sequence between the original and final drawdowns, it hasn’t changed. But, since the tie-ups have changed, the treadling steps have changed!

I have heard people say: the treadling didn’t change but the tie-up did. What they mean is the treadling sequence didn’t change. Think about weaving on a table loom. The levers that you would engage for the final drawdown are not the same as those you would use for the original one. The terminology is confusing.

To avoid the confusion, I use the terms treadling steps for the combination of which treadle I step on and what shafts are attached to it, and treadling sequence for the numerical list of the steps.

For example, in the drawdown above, the first part of my treadling sequence is: 1, 2, 3, 4.

My treadling is:

1, 5, 6, 7

2, 6, 8

1, 3, 5, 7, 8

4, 6, 7, 8

If I were to give you just the treadling sequence 1, 2, 3, 4, you would have no idea how to weave it. But there would be no ambiguity with the treadling steps listed above.

Next, I tried some more options on the same threading, with a different tie-up. Below is the starting drawdown of an example.

To arrive at the final drawdown, I changed both the tie-up and the treadling sequence, as shown below.

Do you see the difference? To avoid half motifs, I changed the treadling sequence; to obtain symmetry I changed the tie-up. Do you see where?

Below is the front and back of the sample woven from the modified drawdown.

|

|

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

Twill Blocks on 8 Shafts |

Marcy Petrini

September, 2024

My blog in August was about developing an eight-shaft tie-up for broken twills blocks, also called false satin. Here is the drawdown as a reminder:

I wove the sample and here it is:

Next, I wove the classical turned twill blocks. Here is the sample:

Below is the drawdown with the tie up for the turned twill blocks; it is derived from the broken twill by returning all quadrant to a straight 1/3 (or 3/1) twill tie-up.

There is a bit of warp left, so rethreading may be in order. There are other options for twill blocks and other structures.

Happy weaving and happy fall.

Marcy

|

Twill Blocks Tie-Up |

Marcy Petrini

August, 2024

It invariably happens that when I teach a topic, I come away with more ideas. I offered a seminar on blocks at Convergence® 2024 and as I was finishing the handout, I thought of things that I wanted to change.

One of the areas is twill blocks on eight shafts. In my monograph on eight shaft twills, I have taken a straight draw and wove the two halves as 1/3 and 3/1 broken twills, forming blocks, one block weft dominant, the other warp dominant and then reversed. We also call these twills false satins, so two blocks of false satins form a false damask.

Below is the drawdown and the fabric woven from it.

There are two lessons to be learned from these figures. We can see that they are formed with broken twills; they are false satin and not true satin blocks because the twill lines are still visible. A true satin has “the suppression of the appearance of diagonals” as defined by Emory (Emory, Irene. The Primary Structure of Fabrics. Washington, D.C.: The Textile Museum, 1980.)

The second lesson is that floats of a 1/3 and 3/1 twill should be three threads long for both weft and warp floats. In the above fabric and drawdown, I wasn’t careful and where the blocks meet, some of the floats carry over into the next block, sometimes resulting in a four-thread float.

In some of the variations of this structure, Carol Strickler in her book (A Weaver’s Book of 8-Shaft Patterns) describes these blocks as having units, one on shafts 1 through 4 forming block A, the other on shafts 5 through 8 for block B. The same twill is used for both units and each unit can be repeated. The drawdown below is an example. Block A is formed with two repeats of the straight twill on four shafts; block B is the same configuration, but on the second set of shafts. The treadling is weaving the blocks to square, one weft dominant, the other warp dominant, and then reversing.

This drawdown also appears in my monograph, and it has the same problem as the previous one: floats continuing into the adjacent block.

Now, however, I want to weave this structure, so it’s time to think about making the floats the correct length. I could just copy the tie-up and treadling from Strickler’s book, but I want to understand how to manipulate the tie-up to achieve that goal. I have seen others just break the twill and not worry about the spill-over floats as I did. We can think about developing the correct tie up. (The next set of figures derive the drawdown; if you don’t want to follow it, see Figure 11, the final result.)

When I weave broken twills, I usually “break” the twill in the threading, between shafts 2 and 3. Thus, the resulting threading is 1, 3, 2, 4. When treadled as a 2/2 straight draw, this has the advantage of not needing floating selvages because of the odd vs. even edges in the threading.

However, straight twill threadings are more versatile for twill blocks. Then the tie-up can be broken. I used the same 1, 3, 2, 4 which resulted in the next drawdown.

This portion of the tie-up and treadling weaves blocks A weft dominant.

We can repeat this tie-up for the second block; however, the weft-dominant tie-up and treadling for block B must occur when block A weaves the warp-dominant twill, as in the drawdown below:

The next step is to find a warp dominant tie up for the shafts 5 through 8. There must be three warp thread and one weft thread for each twill repeat. Warp threads in the warp dominant block B cannot be adjacent to warp threads at the edge of the weft dominant block A. It’s a bit like solving a puzzle.

I approach this tie-up by figuring out which shaft can be tied to which treadle, using the limitations described above.

Shaft 5 can show warp with treadling step 1, 2 and 3, since the adjacent shaft 4 shows weft. Then treadling step 4 for shaft 5 will show weft, since shaft 4 shows warp. The drawdown is below:

We can use the same strategy on the other side of the block, with shaft 8. Shaft 1 shows warp with the first pick, and weft with picks two through four. Thus, shaft 8 must show weft on the first pick and warp for the remaining three, as shown in the drawdown below.

Next, I want to look at the bottom and the top of the warp-dominant block B where it meets the top and bottom of the weft-dominant block B. In order to see top and bottom I must extend the treadling steps 1 through 4.

For treadling step 4, shafts 6 and 7 must show warp since step 5 shows weft. For treadling step 1, shafts 6 and 7 must also show warp since step 8 shows weft.

Next, we need to fill in the treadling by following the rules: warp on shaft 6 for treadling step 3, in order to have a three-thread warp float. Similarly, warp on shaft 7 for treadling step 2.

Our last step is to do the tie-up for warp-dominant block A, which we do in parallel to block B. To complete the drawdown, we repeat treadling steps 5 through 8 again. Below is the final drawdown.

Done! To check that all the floats are never longer than three threads, I use the float analysis of the drawdown software and it confirms it.

Describing the process takes longer than to do the steps!

I figured that there is more than one way to treadle these twill blocks. I was curious what tie-up is used in Strickler’s book, so I did the drawdown exactly as it appears, shown below:

Totally different approach, same result.

While going through the process, I noticed how the tie-up is organized, which is more obvious when looking at it as filled boxes rather than numbers. On the left is the one we just derived, on the right the one from Strickler.

The parallel images of the opposite quadrants and the mirror images of the adjacent quadrants are obvious and can be used to determine a drawdown.

Next time you look at a complicated tie-up, and wonder how the weaver ever arrived at it, now you know!

And the fabric…. The warp is wound…. Stay tuned….

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

Eclipse |

Marcy Petrini

July, 2024

I am fascinated by eclipses of the sun. I can imagine how frightening it must have been in ancient times when people didn’t know what was suddenly causing the covering of the sun during the daytime.

I remember as a child in Rome, Italy, an eclipse was occurring early in the morning. School postponed opening till the peak was over so that everyone could experience the eclipse at home. We lived in an apartment building with a rooftop terrace, and everyone gathered there to watch it. I also remember walking to school partly in the shade as the sun was slowly returning,

In 2017, the eclipse was going to be partial where we live in Jackson, MS, so we traveled to Kentucky for the August 21 totality. We were parked in a field provided by a distillery. For a small fee, and first come, first serve, we found the perfect spot, with lots of kindred spirits watching, cheering and clapping. We brought special glasses that allowed us to look at the eclipse as it evolved. We were lucky, an incredibly clear and blue sky – while the sun was uncovered. Terry had a filter for his camera; he took periodic pictures and then put them together for a short slide show (< 30 sec.). Here it is:

https://terrydwyer.net/images/video/adapting to the dusk of totality.mp4

Back at home, I was inspired to weave this scarf:

I chose M’s & O’s as the structure for my scarf, I don’t remember why; perhaps the O’s reminded me of the sun. I used 10/2 mercerized cotton in a gold color for the warp; the black weft was 20/2 silk, the bright yellow weft was a silk from my stash, close to an 8/2, but the two wefts worked well together despite the difference in size. I divided the 65” length of the scarf in 5” segments, starting with 5” of yellow, introducing ¼” of an inch for the following 5” segment, and then progressing by changing ½ an inch with each 5” segment, until the end, where the last yellow was ¼” and the scarf ended with 5” of block.

I really like the scarf; whenever I need an example of M’s & O’s, I use one of the segments, like the one below.

This year, we travelled to Arkansas for the April 8, 2024, eclipse. Terry chose Lyon College for our site; the college was very welcoming, providing all sorts of programs related to the eclipse, plus food, vendors, and a great spot for us to set up and watch with some faculty and staff. Once again, we were lucky because we had a clear sky. This one was nearly double the totality from the 2017 one, so we were able to take our glasses off and admire for several minutes the sun with its prominences, visible in the photograph that Terry’s took:

Time for a scarf to commemorate this eclipse. This time I decided to make the gradation in the warp. I used 20/2 silk for both the black and the gold with a set of 30 epi. I adjusted the width to 9”, so I could use 9 segments. I started with 30 threads of gold, and ended with 30 threads of black, increasing the black by 3 threads every inch.

Recently I had used the drawdown of the plain back cord from Davison’s book for one of my “Right from the Start” articles in Shuttle Spindle & Dyepot. This seemed a good opportunity to weave the Plain Back Cord Joseph France #23, threading #25; I used the suggestion of cramming in the reed 4 threads out of the 6 of the repeat. Here is the drawdown:

I wove the weft-dominant side on top on the loom. I rearranged Davison’s treadling so I could treadle across the six treadles by repeating the tie-up.

I changed my mind about the weft several times. Ultimately, I decided that a textured weft would capture the idea of the prominences. I also decided that doing a gradation in the weft could be better than a solid color. I chose a rayon boucle from my stash for the gold. I didn’t have enough of a single textured black, rather several ones that I liked, so I decided that I could change the black every so often.

For the gradation I divided the length of the scarf into 9 segments, in parallel with the threading; each was approximately 7.1”. I started with the gold, and increased the amount of black by 10%, except for the first and last segment where the increase was 20%.

I was busy weaving samples on my 8-shaft loom for my Convergence® seminars, so the scarf set unattended for a while. Finally, it’s done! I machine washed it and machine dried it on low to encourage the cord to be more visible.

Here is the scarf, showing the weft dominant side:

The close up below is the warp dominant, showing the cords. The texture from the black yarn is also visible in the close-up.

The next eclipse in the US will be August 23, 2044………. We may have to go elsewhere before then… Spain, August 12, 2026?

Happy Weaving!

Marcy