Lifetime Achievement Award

Marcy Petrini

5/23/2016

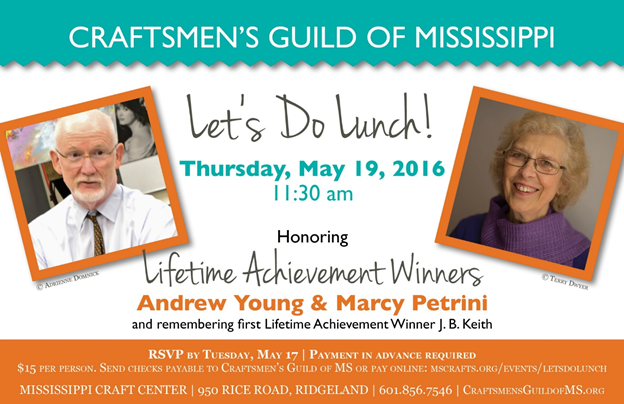

I was very honored this past Thursday (5/19/16) to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Craftsmen’s Guild of Mississippi (CGM) at a Guild Luncheon. I was introduced by Kathy Perito, my co-instructor for the fiber classes at the CGM, who is also an HGA Board member. I was asked to talk about my relationship with the Guild and what follows is a summary of what I said.

I thanked Kathy Perito, Ken McLemore, CGM President, the CGM Board of Directors, and the staff of CGM: Nancy Perkins, CGM Executive Director, Sheri Cox who has been involved with the weaving class for many years in one capacity or the other, and Tomika Cheatham who besides being a financial guru served as the registrar for the weaving classes for many years. I also thanked past Executive Directors for their support and I was happy that VA Patterson, Julia Daily and Kit Davis were present.

My fiber life started early in Italy where all of the women on Dad’s side of the family were fiber people. But it was my Dad who taught me that I could do whatever I set my mind to do (good thing I didn’t want to become a brain surgeon!), but whatever I did, to take it seriously, without taking myself too seriously; this led my weaving from a hobby to become a passion; he also taught me not to plan too closely because life has a way of making its own plan.

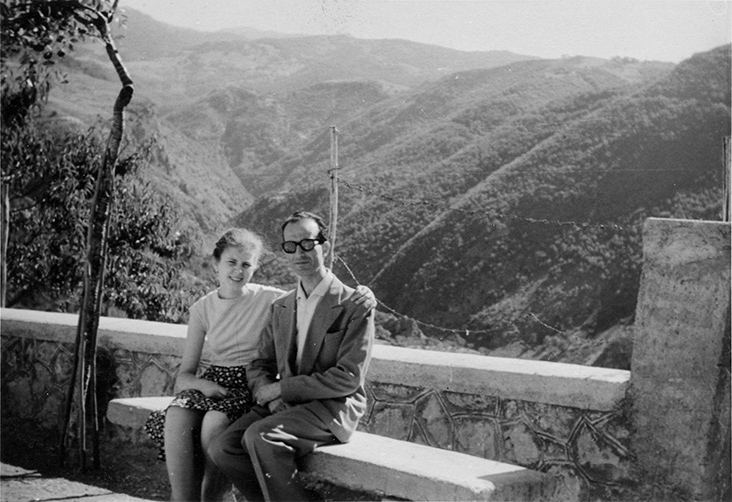

Based on that advice, I decided not to stay in Chicago for my graduate degree but instead to go to the University of Rochester. It seemed crazy at the time, but after some six years, I had met and married my husband Terry Dwyer who build me my loom, learning to weave at the university gallery and got my degree!

When we moved to Mississippi, it was Dan Overly, the Founder of the CGM and its first Executive Director, who convinced me to apply for Guild membership, even though I told him that I didn’t weave enough to sell my work; he pointed out that education is an important part of the Guild. Once accepted, to talked me into teach weaving, even though I objected that I had never taught weaving before.

So started my teaching weaving career. The looms the Guild owned had gone through a flood, needed a lot of work, but luckily Terry was familiar with looms, so he was the one maintaining them. The Guild’s offices and classes were housed in the old President’s House at Millsaps College. The sales gallery, craft demonstrations and festivals were at the then Craft Center on the Natchez Trace, a log cabin owned by the National Park Service. With my weaving class producing new weavers and under Dan leadership, the Chimneyville Weavers Guild became a reality. It flourished and later became the Chimneyville Weavers and Spinners Guild; we will be celebrating our 35th anniversary this fall. Here we are a few years back celebrating my new studio.

When it was time to demolish the President’s House, the Guild’s offices – and the looms – moved to the Craft Building on the Agricultural and Forestry Museum grounds. But we finally got a permanent home! When the new Craft Center was built, the Guild consolidated everything into this wonderful building. Looms had to be moved again – and hopefully for the last time! The studio is smaller, but it’s quality over quantity.

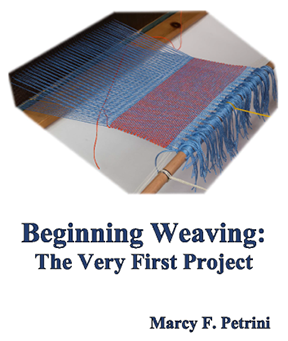

At some point my friend and former student Gio Chinchar asked me whether I didn’t get tired week in and week out to go teach the same class. And I said, no, it wasn’t really the same class; new students come, new challenges arise as we have a seemingly infinite number of combinations of fiber, yarns, colors and weaving structures. Each class is different and the teaching has progressed to writing, starting with the handouts I provided for the students. This led to my writing. In the late 90s I was asked to write a column called Right from the Start for Shuttle Spindle & Dyepot, the periodical of the Handweavers Guild of America. I became its regular columnist and I just wrote my 70th article. Now we also publish monographs on various weaving topics.

But I started thinking about the future; I couldn’t teach the class forever and I didn’t just want to walk away from a 35-year long project. At some point I would need to find someone to take over, but who? One happy day, this great lady entered into my life. Here is Kathy (Perito) with me at the Guild’s 40th Anniversary party. Kathy started as a student and it became obvious that she “got it” from day one. She became my assistant, and soon after my co-instructor. She quickly learned weaving structures, understands the looms, has great creativity and a can-do attitude that makes the class really fun. And it’s a great luxury for me – she does all the hard work, I get to think about what students need to know so I can write about it!

None of this would have been possible without this wonderful man, my husband Terry (Dwyer). He built my first loom, in the front of the studio here, maintained those in the Guild for many years, and assembled the computerized loom, in the back of the studio in the picture, from many, many boxes; he is the webmaster for my website and posts my weekly blogs. And here he is making a mess of my studio to take pictures, but then, I need those pictures!

And here are some of the photos he took of my work. I don’t sell my pieces because every one of them is one of a kind that I need for my teaching and my writing; each one is an example of a weaving structure, technique, fiber, yarn, or color combination. I think of them as my reference library.

Again, I am greatly honored and very happy to have been a part of the Guild all these years.

Please email comments and questions to

Rules

Marcy Petrini

5/16/2016

I like to go with the flow – make up knitting patterns as I work, cook without recipes, travel with vague plans. Even in my weaving I like to design my pieces, leave my weft yarn options open, and sometimes unweave and re-thread or re-sley because I just didn’t like the way the weaving looked.

But I also know that we need rules, in weaving and in life. Imagine someone driving at 65 mph in a small neighborhood street. In weaving, I like to divide my rules into three sets.

The first is the rule that we all use, our language, if you will. When I say that I wove a table runner in huck, you know exactly what I mean – if you know the vocabulary. You may not know the exact threading, but you get an idea of what my runner may look like. And, as shown below, you may even know that you can weave warp and weft floats on both sides of the cloth.

The second class of rules are for the way we do things. As a teacher, I try very hard not to say “always” or “never” or “you must”, because people are different, looms are different and we all have preferences. What may be easy for someone with long arms, won’t work for someone with shorter ones, for example. But whenever I discuss how I do things, I also explain why I do the things the way I do them. For example, I say that I dress my loom from the back to the front to minimize the wear and tear of my warp threads by having them go through the heddles and reed only once. Any mixing of warp ends that I like to do at the loom, I can accomplish by using more than one warp.

The last set has rules that I use for myself, to overcome my poor tendencies, or to make my weaving easier, or to make myself accountable.

The one that I follow most religiously is: “never have a naked loom”. I learned from experience that if I take a project off one of the looms, and then start the planning for the next project, there will be procrastination and the loom will sit “naked” – empty – longer than it needs to be. I am not sure why. I like to weave, I enjoy every step of the process, perhaps some more than others, but still, a loom without a warp is a psychological barrier, and even having a bout laying on top of it is enough to get that next project going.

So, this is what I do: I start winding the warp for the next project while weaving the current piece. If I am delayed and I don’t wind a new warp before the current project is done, I simply don’t take it off until I have a least a bout wound. Then I can take the project off and lay the bout on the loom, which is thus no longer naked.

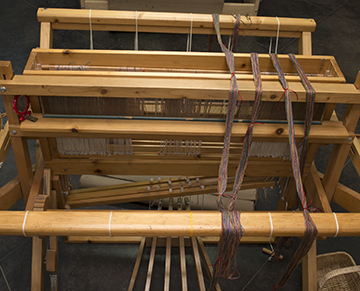

Here is my loom waiting for more bouts, so the warp can be wound.

What rules do you use?

Please email comments and questions to

Inspiration

Marcy Petrini

5/9/2016

I have completed another handout for Convergence®, so I decided that I should reward myself with a short trip to Laurel, MS, a couple of hours southeast of Jackson, where a gem of a small museum, the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, is hosting a gorgeous exhibit of Dale Chihuly’s work, called Venetians, glass vessels inspired by the famed work from Venice. That was his source of inspiration; his colors, that covered the gamut of the rainbow, are mine.

The trip got me thinking about inspiration and how we may use it.

I have decided that there are two kinds of inspiration: the looking and the doing. Both can lead to a change in path.

In the case of looking, seeing art objects, especially colorful ones, affects me pretty much as nature does: this time, I didn’t come home and weave Chihuly’s colors right away, as I have done in the past (Blog #2, Colors in Nature, November 30, 2015), but I know that they will find their way in my weaving sometime in the future, especially since I bought the book! That happened with this shawl, inspired by the purple irises with their gold middle that grow in our front yard. The shawl is woven in huck with silk and gold stripes as well as some gold in-lay. I didn’t even know that those iris colors had sneaked into my weaving!

The “doing” for inspiration occurs when I take a class outside my field. I have woven long enough that I can learn new techniques by reading about them and then trying them. But just as looking at color in glass inspires my weaving, so doing other art forms feeds my art. At this upcoming Convergence® I will be taking a super seminar by Judy Dominic called Soft Paperless Books. Judy is a terrific artist and teacher with incredible creativity. Do I want to start making paperless books? Not my intention, but it could happen. I just think that “creating outside the box” – or is it inside the book? – is good for one’s inspiration. Although I must admit that I once took a spinning class just because as a weaver I thought I should know more about how yarn is made and, twenty-eight years later, I am still spinning!

Convergence® offers a wonderful opportunity to “create outside the box”; I have taken many seminars with technique I haven’t used since, but I know that, just as the iris colors sneaked into my shawl, new techniques sneak into my creativity.

Please email comments and questions to

From Four to More

Marcy Petrini

5/2/2016

In last week’s blog I mentioned that I like to think of two methods for extending weaving structures from four to eight shafts; one way is to simply extend the threading; the other way is to divide the eight shafts into two sets, which I call the “front” loom (1, 2, 3, 4) and the “back” loom (5, 6, 7, 8).

The methods are not clear cut, but they have helped my students use those extra shafts. Surveys have shown that weavers buy eight shaft looms, but often just use four, perhaps because there can be some difficulties – namely floats – that have to be solved with the extension.

We can apply the two methods to overshot and monks’ belts. For a simple extension to eight shafts, the four-blocks of overshot listed last week become:

|

Block A |

1, 2, 1, 2, repeat |

|

Block B |

2, 3, 2, 3, repeat |

|

Block C |

3, 4, 3, 4, repeat |

|

Block D |

4, 5, 4, 5, repeat |

|

Block E |

5, 6, 5, 6, repeat |

|

Block F |

6, 7, 6, 7, repeat |

|

Block G |

7, 8, 7, 8, repeat |

|

Block H |

8, 1, 8, 1, repeat |

The process works for threading, but the treadling presents the float difficulty. Look at the drawdown below where the blocks were woven one at a time, as it is done in 4-shaft overshot. This is for a sinking shed loom. As in four shafts, when we weave one block, shown in yellow weft here, we obtain half tones in the two adjacent blocks; the problem becomes that there are five blocks remaining; the solid red represents areas of plain weave, since the drawdown only shows the pattern weft; but wherever plain weave appears on this side of the cloth, there will be weft floats on the other. Treadling a single block produces continuous floats over five blocks (right click to open a larger image in a new tab).

The solution is to break up the blocks in the threading, or combine blocks in the treadling, or vary the size of the blocks, or a combination of these.

For monks’ belts, we can use the idea of a front and back loom; these are the blocks:

|

“Front” Loom |

“Back” Loom |

||

|

Block A |

1, 2, 1, 2, repeat |

Block C |

5, 6, 5, 6, repeat |

|

Block B |

3, 4, 3, 4, repeat |

Block D |

7, 8, 7, 8, repeat |

Then in treadling, we have to weave the front and back looms at the same time. We already know from four shafts that only one block at a time can be woven because of the floats, with two looms, we can have four possible combinations: block A with either C or D; and block B with either C or D.

However, the float problem persists, but not as extensive as in overshot: there are two combinations that are viable. Look at the drawdown below, also for a sinking shed loom. The orange represents areas of weft floats; whenever the floats are over two blocks, they are too long. The blue represents areas of plain weave, which, however, are floats on the other side of the fabric. Thus, for this threading, A & C, and B & D produce reasonable floats.

In this case, using the front and back loom idea helped us eliminate some floats. If we had extended the threading for monks’ belts as we did in overshot, we would have started weaving one block at a time, and it would have taken us longer to arrive at the combinations that work.

This front-and-back-loom method works particularly well when we want to combine structures. We could weave a twill in the front loom and huck in the back loom. Even without extending the threading, the possibilities are staggering.

Please email comments and questions to

What's in a name?

Marcy Petrini

4/25/2016

I find it very confusing when people use the incorrect terminology to describe an entity. My husband Terry Dwyer always says that the vocabulary in any given field is a good part of learning that discipline, be it medicine or weaving. And my advisor in graduate school would always insist on not changing the meaning of a word for our convenience, or even inventing one when there was a perfectly good term already available. Perhaps that is the reason why redefining terms drives me crazy, whether it’s the “crab cake” made with tofu and herbs in a menu, or the description of the natural media of “wood, paper, plastic, and graphite” used by a New Orleans artist, or color-and-weave as we talked about in my April 11, 2016 blog; what’s wrong with tofu cakes? Or man-made plastic as an art medium? Or a colorful twill scarf? The more exact we are with our vocabulary, the clearer the information we are trying to convey.

Unfortunately, there are ambiguities, especially when we use more than four shafts, although last week (blog of April 25, 2016), we talked about shadow weave on four shafts appearing in two ways just by changing the order of the colors in the treadling: as a weaving structure shadowed, or as totally different color-and-weave motifs.

Another ambiguity that I have run across is overshot and monks’ belts. Both structures are supplementary weft weaves, with a pattern weft, loftier and larger than the ground warp and weft, which forms blocks superimposed to the ground cloth. Below is a sample of overshot with its characteristics three areas: the overshot area, the blue blocks in this sample; the plain weave area, in white; and the half-tones, showing grids of blue and white.

Whenever a block appears on one side of the fabric, there is plain weave on the other, and vice versa. The half-tone areas are formed by the sharing of shafts between blocks which are derived from twills: block A is threaded 1, 2, repeat; block B is threaded 2, 3 repeat; block C is threaded 3, 4, repeat; and block D is treaded 4, 1, repeat.

In contrast, monks’ belts, shown below, has no half tone areas, because there is no sharing of shafts between blocks; while overshot has four possible blocks on four shafts, because of the sharing, monks’ belts has only two: block A is 1, 2, repeat; block b is 3, 4, repeat.

Is monks’ belts just a variation of overshot? It has been called overshot on opposite (since block B is threaded with the opposite shafts of block A). Or is it its own weaving structure since it lacks the half tones which are characteristic of overshot?

When we move from four shafts to eight shafts, another complication arises that adds to this confusion: floats. Do you see why?

How overshot and monks’ belts are extended from four to eight shafts are examples of the two methods that I like to think can be used for this extension. This is a topic that I will discuss at the More Than Four super seminar at Convergence®, and there will be a brief introduction in my next blog.

Please email comments and questions to