Winter 2020: A Glimmer of Hope

Marcy Petrini

February, 2021

Here is the shawl by that name:

With winter come the holidays and with the holidays come parties, travel and family get together, which led to more Covid-19 cases and more deaths. Unless you stay home and miss it all.

In the middle of this depressing season, came a glimmer of hope: vaccines approved for emergency use, which basically means that they are effective, but there is a lot we don’t know about them, they are mRNA vaccines, they work differently than the usual flu vaccines. mRNA vaccines have been in the making for a long time, notably for the SARS-I, but when that epidemic was averted, funding for the vaccine type decreased and thus it took longer for the SARS-II, aka Covid-19 vaccine to come into being.

Colleagues in the health care field were getting vaccinated; they talked about the few side effects, and the relief that they felt having some protection. Just a few months and we, too, could be vaccinated.

That glimmer of hope translated to green threads to me. Green seems to be a common color for hope. I used 2 threads of 10/2 green silk from RedFish Dyepworks. The fabric is plain weave, so in order to have a solid line of green, I needed two threads. Here is a close-up of the fabric:

And white is associated with winter, I guess because of the snow. Even I think of white for winter, although I didn’t see snow until I was 13 and then it was not love at first sight – my first step into the white stuff resulted in my sliding into the snow with a sore bottom. And I have lived in the South for over 40 years where I can count on my one hand, the number of snow storms we have had, most of which were gone overnight. Ironically, while I was weaving this piece, Mississippi had the worst snow storm that I can remember. The city shot down for a week.

The white warp was easy enough; I have a silk from my stash, close to 20/2. The weft I had to think about. I wanted texture, but not hair yarn, for example. I thought of textured handspun, but I only have a couple of bobbins in reds; I would have to spin some, not a good option. I looked through my shelf that holds black and white yarns and there was my answer: white silk bouclé.

I had bought several skeins of silk bouclé dyed for the colors of the Convergence® in Long Beach, CA by RedFish Dyeworks. I loved the yarn feel and look; I wove this shawl with it:

And here is a close-up:

At the Convergence® Marketplace, I wanted to buy more silk bouclé from RedFish in different colors, but they only had 5 skeins of white. I bought those, thinking that I would dye them.

The dyeing never occurred, but the white yarn was perfect for this project. I thought of using it for warp and weft as I had done for the colorful shawl above, but 5 skeins wasn’t enough: each has 150 yards for 100 grams. I used nearly 4 for the weft alone.

I opened up the sett for the 10/2 silk warp to 18 epi to accommodate the larger weft. There are 5 two-threads green silk threads dispersed over the width of the shawl, 22” on the loom; that translates to the green every 4th inch, except at the edge which ends with 3” of white.

The final shawl is 19” by 95”. This is one piece out of the Covid-19 series that I will wear, maybe to concerts for the 2021-22 season.

Stay safe and happy weaving!

Marcy

Fall 2020: Fire and Ashes, Water and Mud – Amidst Covid.

Marcy Petrini

January, 2021

Here is the scarf by that name:

As summer gently slipped into fall, we continued our daily and weekly routines to keep body and souls together.

The inside world was good enough, but the outside a disaster. By Labor Day this country had 22% of the world’s deaths, even though our population is only 4%: 183,000, the numbers are both staggering and numbing. And unemployment, failed businesses… and then racist violence.

Just as we thought we couldn’t handle anymore, Mother Nature lashed her anger. Fires out west, tornadoes on the Gulf Coast – heart-wrenching devastation.

I turned to my weaving.

The colors from the reports were vivid. The colors would tell the story.

I found some 5/2 silk that would be appropriate for the rigid heddle, with a sett of 12. Starting with the red fires turning to black ashes on one side, and starting with aqua, turning multi-colors of brown, greenish, blackish, as the water retreated and left mud. The ashes and mud met in the middle. The red seemed to have given away to grey in the virus, but there is red for blood from the violence, too.

I envisioned a slightly warp dominant plain weave, to focus on the colors. So, for weft I thought I had just the perfect yarn: a multicolored black to white silk, with lots of greys. When I found the yarn on my shelf, although I still love it and I have used it in a couple of projects, it was bigger than I had remembered. It was worth the try, anyway.

I made the hem with some of the 5/2 black, thinking that it would work better than the multicolored silk, especially if I decided not to use that silk.

After weaving a few inches, the result was a weft-dominant fabric with irregular stripes of black, grey and white. Not the look I was going for. Back to the drawing board for weft.

On the shelf there was a big cone of an identified grey cotton, unmercerized with a nice sheen, which wraps at 30 epi, probably 8/2. I tried it. It worked perfectly. Large enough to make the fabric stable, but small enough to result in a warp dominant scarf, not adding to the weight and keeping a good drape.

So, I wove away and finally got to the end. I hemmed it with the grey cotton. Time to unroll, only to stop dead on my tracks. I had completely forgotten about the hem with the fat 5/2 black silk at the beginning of the scarf. I tried to convince myself that it would be all right, but I wasn’t convinced enough to take the scarf off the loom. I left it overnight to make a decision.

The next morning, in the bright light of my studio, the original hem looked even worse. I decided I would use the grey cotton and hem the beginning of the scarf before I cut off the black silk hem which I could use as a guide. I sewed the hem and took the scarf off the loom.

As I was about to cut off the original black hem before wet finishing, I noticed that the grey hem from the night before was not straight. Sometimes I caught 2 weft threads, sometimes 3. Now determined that it was going to be right, I cut off the new grey hem, placed a white guide thread up to where the hem should catch and hemmed it again. This time it was successful. I was able to pull out the white guide thread and cut off the black silk hem. Finally ready for wet finishing

I am thinking that this scarf took longer to hem than it did to weave! But it’s done. Here is a close up.

Meanwhile, winter started rolling around…..

Stay safe and happy weaving!

Marcy

2020: The Spring That Never Was

and Summer through My Window, no Place to Go

Marcy Petrini

December, 2020

Here is the scarf:

2020: The Spring That Never Was

No, it’s not very “pretty”, but neither are the deaths of nearly 120,000 Americans for whom spring never was.

Spring comes early to Mississippi. The yellow-green pine pollens blanket the neighborhood: the ground, cars, roofs. The first spring rain washes out the pollens and gives way to more greens, bright at first, then turning darker. But in my mind that green became darker and darker as spring progressed. Dark army green. After all, this is a war we are fighting against this virus.

Yes, there are the dumb deaths: “It’s just a little cold”, which it is, until it isn’t.

Or the foolish deaths: “Let’s have a covid party, that way we can get infected and then go on with the rest of our lives.” Except the virus decides whether there is a “rest of your life.”

But I am saddened by the death of those who caught the virus early on, before we knew how infectious it can be before symptoms, or even without; before we knew that masks and social distancing can help.

And my heart does to the elderly and the disabled who lived in facilities where the caring and respite turned into death row. Or the grandma whose grandson thought “it is just a little cold.”

But most of all my heart is broken by the deaths of the health care givers and first responders who died helping others, sometimes with little protection, knowing the danger but choosing to do what was right for their patients. And made the ultimate sacrifice.

So I turned to my weaving. I envisioned a green scarf with progressively darker greens. Not much blending, deaths marches on in a linear way.

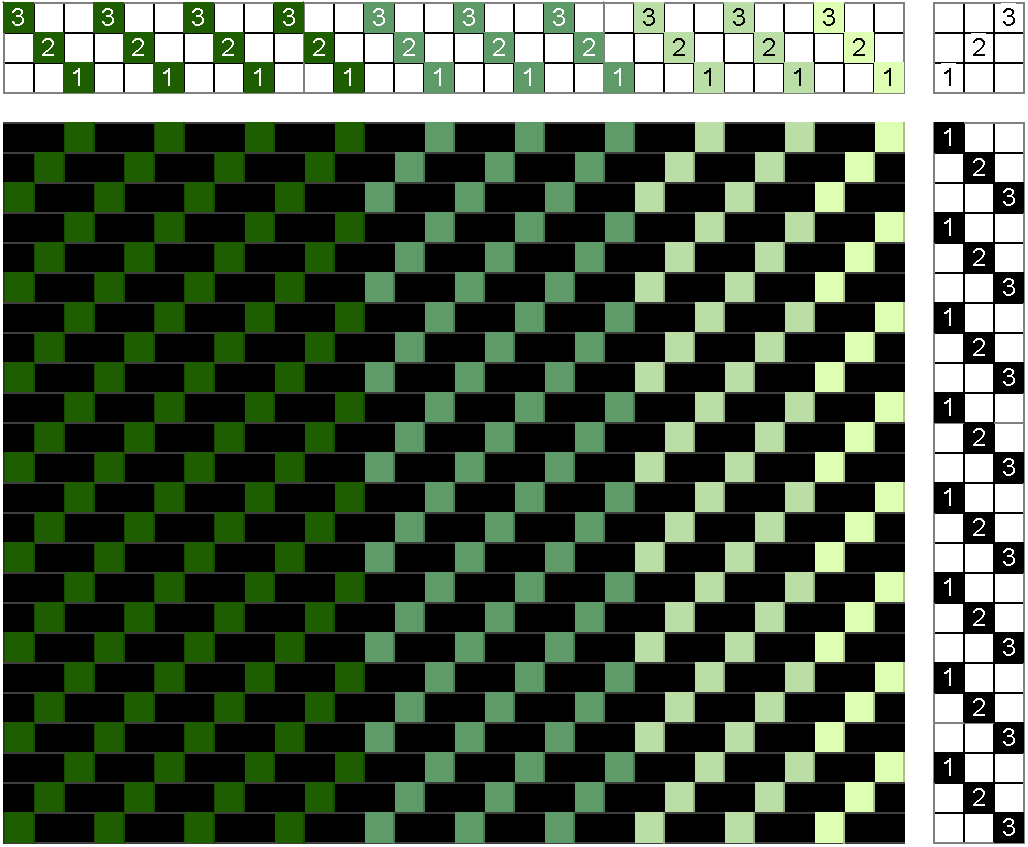

I wanted the fabric to be two sided, but not overwhelming so. I thought a 2/1 twill would provide it. The 10/2 cottons from Lunatic Fringe offer a variety of greens; I used 7 in the warp, sett at 30 epi, and planned on 10/2 black for weft. The drawdown is below (with a reduced number of greens).

I hadn’t woven a 2/1 twill in a long time; more recently I wove a 3/1 twill, but it was a while back, too. My recollection, however, was that the edges of such an unbalanced fabric can curl up. I thought I could prevent it by threading a selvage, using the 4th shaft that was not part of the twill; I could thread a pseudo basket weave, which would still need floating selvages, but provide some stability and prevent the curling. The drawdown is shown below.

I began to weave, but the 10/2 black just didn’t match the idea I had in mind. I decided there wasn’t enough texture. I tried a couple different wefts, and finally I found on my shelf the Universal Yarn “Bamboo Bloom Lights out”, black, thick & thin, 48% bamboo, 44% wool, 8% acrylic. The thick and thin provided the texture.

I also didn’t like the pseudo basket weave at the edge, probably because the sett of 30 epi was too close, but also the intersections didn’t look right with the bamboo blend. So, I took the 6 threads on each side and rethreaded and re-sleyed them for the twill. I was finally ready to go.

It’s not unusual for me, if I am weaving with something specific in mind, to rework the project as I go. I change wefts often, I re-sley if need be. Sometimes changing the weft results in needing a different sett. I have also re-threaded if I haven’t liked the pattern after all. I think of my warp as a canvas, it does not need to be static.

The scarf is a bit heavy but it has some drape, certainly less than my usual scarves. But that’s ok, this is one scarf I don’t plan on wearing.

Here are the close ups of the fabric:

|

|

On the left is the top as I was weaving; because the floats are only over 2 threads, and the sett is rather dense, what we may expect as the weft-dominant side is not. On the right is the bottom as I was weaving, warp dominant, with the weft poking through in the thick parts.

At the end of a project, I always ask myself: if I were to do this again, what would I do differently. In this case, I think the 3/1 twill would have made the weft-dominant and warp dominant more obvious. And the thick and thin yarn would probably have prevented the curling anyway. Each project offers some learning.

As macabre as it may sound, while I was weaving, I thought of all the dead underneath the earth, looking up to our green spring. They are gone. We could have prevented a lot of those deaths. We didn’t.

Here is the scarf:

2020: Summer Through My Window, No Place to Go

Memorial Day weekend is the unofficial beginning of summer and what a better way to start than a Mississippi Symphony Orchestra concert on the grounds in front of the Vicksburg Military Park. But in 2020, cancelled.

There is no more relaxing way to spend summer evenings than at the ballpark, cheering our local team, the Mississippi Braves. But in 2020, no minor league baseball.

Wherever I go, my travel journal goes with me. This year it stayed in the drawer. No Convergence®, no travel, not even a little excursion.

But I have my window, a great view of the backyard from my studio.

Really, I can’t complain. I have my health, good food, shelter, work that keeps me busy and happy, and the good companionship of my husband. I have so much while others have nothing.

In the evenings we sit in the patio right outside the studio window, but during the day, I watch from inside. It’s hot and humid outside, so Mother Nature’s colors are muted: the golden sun filtering through the greens of the trees and plants; the blue of the jays as they fly around looking for their favorite seed, the blackbirds’ feathers so shiny that they looks purple.

And the reds: the red of the hummingbirds as they flutter by the feeder, the crimson of the male cardinals looking for a mate; the showy reddish pink of the throats of the lizards as they scurry along the small wall in front of the studio, the bright red of the woodpecker on the tree across the yard, and the burgundy of the fruits of the two cacti that Terry rescued when the local Mexican restaurant closed.

I love those reds.

But then I think of covid red.

How did covid become red? The now familiar picture of the round virus with spikes comes from electron micrographs, which are in black and white, not red.

Did an artist render it red early on to alert of danger?

Did a pulmonologist describe the red inflammation caused by the virus in the damaged lungs of his patient?

Did the cardiologist fear the red clots that could kill her patients just as they seemed to turn the corner?

I don’t know, but red it is.

I try to look at the beauty and not think of that red.

So, I decided to weave it.

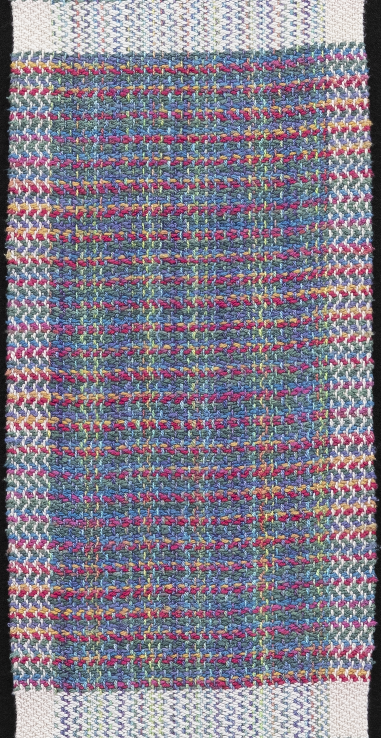

I chose some 10/2 Tencel left over from past Convergences®, by Just Our Yarn, Water and Fire, alternating with Wood Violet in the warp, sett at 24 epi.

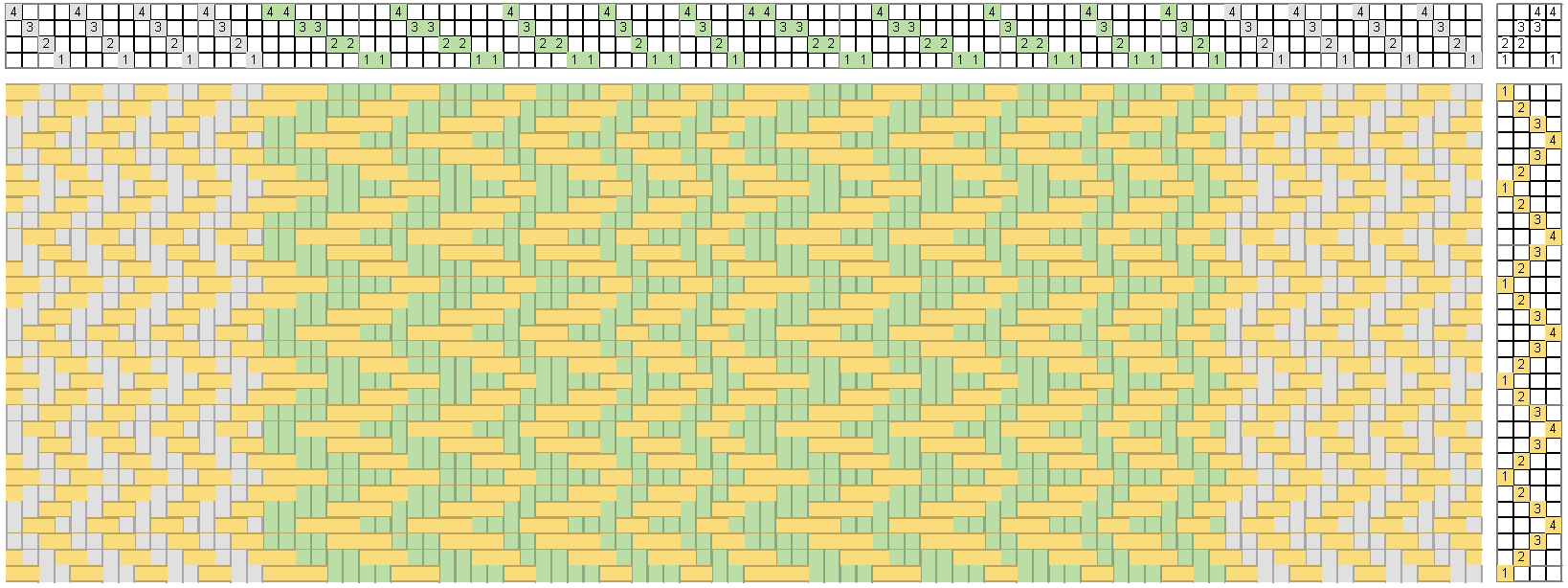

For the structure, I wanted a twill, but I wanted the floats to be of different lengths and not in the same direction, so I used an undulating twill threading with a pointed twill treadling. At that close scale, I knew the twill would not show, but my plan was for the twill floats and their directions, not the actual pattern.

That’s for the view. My window frames are painted off white, so I needed an off white border. I found some shiny silk in my stash, which I set at 16 epi, 1” on each side, threaded as a straight draw. Below is the drawdown of one repeat of the twill with the two edges. I used floating selvages since a pointed twill treadling doesn’t catch every warp thread.

The plan was to weave 1” with the off-white silk, 12” with a weft yet-to-be-determined, and another 1” of off-white silk to make the “windows.”

Where the off-white silk weft crossed the warp in the middle, the colors of the warp show up, but that is ok, my window frames are shiny, and they reflect the outside colors.

After the 1” of off-white silk, I started trying various colors of 10/2 Tencel and 20/2 silk, which are close enough in size to work well with the 10/2 Tencel warp.

Nothing worked. The colors blended too much.

I should have thought that there would be optical blending, with so many colors and relatively small threads, especially from a bit of a distance, as we would be looking at a scarf being worn. Normally our brains first detect the edge of a shape, then the color is filled in; this is called the edge effect. But if we have poor resolution of the shapes, as with small threads, the brain cannot distinguish the shapes and it blends the colors. This is a useful technique when we want to work it that way – we can put red and blue together and the piece will look purple from the optical blending. But I wanted individual colors to appear and not blend, so using the same size weft on a multicolor warp did not work well. Back to the yarn shelf.

I found a matt 100% silk hand-dyed by Margaret Pittman of Heritage Yarns who has sadly now retired. Her colors have always been wonderful. The yarn has reds, greens, blue, purples, and gold, variegated, which Margaret called Spring at Rocky Springs (a real place in Mississippi), but those are the colors in my yard. There were 16 picks per inch once I started weaving, which made the scarf more weft dominant.

Here is a close up of the “window”:

Despite being weft-dominant, the scarf drapes well, silk, even matt provides the drape.

Just as I was getting used to the new – hopefully temporary – normal, autumn rolled around with more destruction. When will this end?

Stay well and safe – and happy weaving!

Please email comments and questions to

Even in the Darkness There is a Rainbow

Marcy Petrini

November, 2020

Here is the scarf by that name, woven with 20/2 silk.

Here is a close up:

And here is the story of the scarf:

On March 11, 2020, we had gone to a Carole King-themed concert. No virus yet in Mississippi, I was both hopeful – maybe in denial – and scared; at the concert I looked around me at the packed auditorium and wondered where were those people from? Is anybody coughing? Sneezing?

At the end of the concert we got into our car, I turned on my phone as I usually do, and as Terry was driving up the ramp to the highway on the way home, the phone beeped: a text from my sister Ellie in Colorado. Not unusual, we text all the times. But this one was different; she said: “I know you are at the concert and I am sorry to be the first one to tell you, but they reported the first case in Mississippi. I figured you will find out soon enough anyway.” My heart sank.

A week later there was the first death. Being in the high risk group, we quarantined ourselves; being home isn’t too bad; sure, we miss seeing our friends and concerts and plays and baseball, which was cancelled for our AA team anyway. But I have my fiber work, Terry his photography and gardening and soon we were zooming for meetings, classes, happy hours and dinners.

But what was depressing to me was the number of deaths mounting. Our Department of Health reports daily and we track cases and deaths. By mid-April it was clear that deaths were accelerating. I started finding out of friends who lost dear ones.

On a rainy day, I was sitting at my worktable in my studio looking out of the window into our yard. It was as gloomy outside as it was on my screen with the latest death report.

Suddenly, from the darkest part of the sky, a rainbow in all its glorious colors appeared. “Even in darkness there is a rainbow,” I thought.

As cases and deaths kept on increasing, I often thought of that day, and finally I decided that I needed to weave it. At the beginning of July I had a free loom, and I could get started. It became the first piece of what I hope will be a covid-19 series.

“Even in the darkness there is a rainbow.” Since I weave lots of scarves, this, too, would be a scarf. Darkness: black silk. Rainbow: obvious colors! I looked through my stash and black silk is not a problem, lots of it. I had all of the rainbow colors in silk, but not in the same size, 20/2 is good for scarves. I figured out what I needed and ordered from my favorite vendor who is fast and reliable. I usually get my order in 2-3 days.

Meanwhile, I started to think about the pattern. I wanted the background to be, well, a background, black, with rainbow color stripes. I could weave it with a black silk weft, same as the warp. I wanted the stripes to stand out, so I needed a structure that would allow me to show the color, but still suitable for a scarf.

I remembered that some bird’s eye twills can have interesting motifs and they may work for the stripes I wanted. I looked in Davison’s A Handweaver’s Pattern Book and on page 15 I found what she calls Joseph France’s No. 11. I had used the # I and liked it, so I started with that draft. It reminds of Myggtjäll.

I could use the 1, 2, 1 threading for my stripes but I needed more than one motif for my scale; sett at 24 epi, the motif would be only 1/8”, I wanted it a bit bigger. I could repeat the motif by anchoring some floats with a thread on shaft 4 as I may do for huck.

This is what I had in mind for stripes:

The background needed to be plain weave; I could use shaft 3 and 4; this was my next step:

The floats are not workable! To weave 3 vs. 4 for my background I needed to treadle 3 vs. 4; and because the threading across the fabric is odd vs. even, I needed the treadle 1 & 3 vs. 2 & 4.

After some rearranging so that I would weave odd vs. even in sequence, I arrived at the drawdown I used, shown below; the weft is in dark grey in the drawdown to make the intersection between warp and weft visible, but the weft was the same 20/2 black silk as the warp.

And this is the drawdown for the back of the fabric:

As I was weaving, I did think about the nearly 1,000 deaths in Mississippi and nearly 120,000 in the US by the end of spring….. that got me thinking about my next covid-19 piece.

Stay safe and healthy – and happy weaving!

Please email comments and questions to

Yarn Systems

Marcy Petrini

October, 2020

“How come, asked Laura, that the sett for this project is 24 epi when the sett from my previous project was 30 epi? They are both 20/2 and plain weave.”

The answer is that the previous project was 20/2 cotton and the current project is 20/2 silk.

But that’s no answer, really. The real answer is: the yarn systems. Just like the measures of length were developed in different places as the metric and the English systems, so each yarn production was limited to a region, and a local system was developed.

Below is the comparison for Laura’s and other 20/2 yarns. Yarns are usually labeled with two numbers; the first generally represents the size or grist of the yarn, the second number represents the ply, the number of strands twisted together. Thus all of the yarns listed below are 2 plies because they are all 20/2. But look at the difference in yards/lb.: the larger than number, the more yards to the lb., the thinner the yarn, the closer the sett.

|

Yarn 20/2 |

Yards/lb. |

Warp Sett (epi) |

|

Linen |

3,000 |

24 - 30 |

|

Silk (Spun Bombyx) |

5,000 |

24 - 28 |

|

Wool (Worsted) |

5,600 |

20 - 30 |

|

Cotton |

8,400 |

30 - 48 |

Today we don’t really need to know about the details of the yarn systems. Yarn vendors nicely tell us yards per lb. so we can convert our warp and weft length calculations to the amount of yarn weight we need to purchase. They even give us helpful hints for the appropriate setts.

But how do they get the information? From the yarn systems.

I first learned about the yarn systems from an article by Walter Houser called ”Yarn Counts” that appeared in The Weaver’s Journal, Fall 1983, on page 52. Other information is newer, and I often deduced it from what the vendors list for yards/lb. Tencel®, and other yarns extruded form natural materials, for example, use the cotton count and so does cottolin. But the Houser article gives us the foundation.

The first number is the relationship between length and weight, either weight per unit length or length per unit weight. When the length is expressed in skeins, the actual length of the skein varies with the fiber. Here some of the most commonly used systems:

|

Yarn System |

First # |

Conversion Factor |

Second # |

|

Cotton |

Skeins / lb. |

840 yards (cotton count) |

Ply |

|

Worsted Bradford |

Skeins / lb. |

560 yards (worsted count) |

Ply |

|

Woolen |

Skeins / lb. |

1600 yards (run) |

Ply |

|

Linen |

Skeins / lb. |

300 yards (lea) |

Ply |

|

Dernier Silk Filament |

Grams/length |

9,000 meter (Den) |

*Tolerance, high and low average |

|

Jute |

lb./length |

14,400 yards (Spindle) |

|

|

Novelty yarns |

Yards/lb. |

|

|

|

European System |

Meters/grams |

|

|

* The tolerance is for silk before being degummed; ready for use is 25% to 30% lighter.

We can use the table above to obtain the same information that yarn vendors give us. Let’s use cotton as an example,

One lb. of a 1 cc (cotton count) yarn by definition is 840 yards long (single ply). This is the standard skein.

|

CC |

Length |

Weight |

|

1 |

______________ |

|

A 2 cc yarn means that 2 skeins (each 840 yarns long) will weigh 1 lb. Thus, a 2 cc yarn has 1680 yards to the lb. (840 yd/skein times 2 skeins). This yarn is half the size of the 1 cc.

|

CC |

Length |

Weight |

|

2 |

________________________________________________________ |

|

In general, the larger the count, the smaller the yarn, since so many more “skeins” (each 840 yards for cotton) have to fit into a pound.

The above statements are true for 1-ply yarn. If we take the 1 cc skein and ply it into 2 strands, the yardage will be half, but the weight is the same. A 1/2 cotton yarn is 420 yards to the lb. The two-ply, of course will be thicker than the 1-ply of the same yarn count, but not double. Jill Duarte (Ply Autumn 2020, page 36) says that a 2-ply handspun yarn is about 1½ times the singles that make it up because of the strands winding around each other. The same must be true of commercial yarn.

|

CC |

Length |

Weight |

|

|

=========== |

|

If we take a 2 cc yarn which has 1680 yards to the lb. and ply it into 2 strands, the yardage will be half, 840, for the same weight, back to the original yardage. The size will also be larger because there are 2 strands, but approximately 1½ times the size of the singles.

|

CC |

Length |

Weight |

|

|

============ |

|

Let’s use an example from a common yarn, 8/2 cotton.

The “8” means that there are 8 skeins in 1 lb. of yarn, each skein 840 yards:

8 skeins x 840 yards/ skein = 6,720 yards

The yarn has been plied, which we know from the “2”, thus for 1 lb. our yardage is:

6,720 yards / 2 = 3,360 yards /lb.

Which is what we find listed from yarn vendors. Incidentally, mercerization does not change the cotton count.

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, here is a comparison of cottons. The gold is 3/2, the blue is 5/2 and the orange is 10/2, all mercerized. This is what our yarn vendors tell us:

3/2 cotton = 3 skeins x 840 yards/skein / 2 skeins/lb. = 1,260 yards/lb.

5/2 cotton = 5 skeins x 840 yards/skein / 2 skeins/lb. = 2,100 yards/lb.

10/2 cotton = 10 skeins x 840 yards/skein / 2 skeins/lb. = 4,200 yards/lb.

Note that 10/2 cotton has twice the yards/lb. than 5/2 cotton, as we expect.

Next time you purchase yarn, make sure you look at the recommended sett by the vendor and remember that the sett of two yarns with same numerical description won’t be the same if the fiber is different.

Happy weaving!