From Four Shafts to Eight Shafts

Marcy Petrini

November, 2019

This month I gave a program on “From Four Shafts to Eight-Shafts” to my guild, the Chimneyville Weavers and Spinners Guild. I have presented seminars and workshops in the past, I wrote a monograph on the topic, and I wrote briefly about one aspect of it in my May 2016 blog. But whenever I am to present a topic, I like to rethink of it because difference circumstances require different presentations and, for a short program, it’s best to address the big picture with some examples to clarify.

I like to think of the transition from four shafts to eight – or more – as falling into four broad categories: 1) structures that can be simply extended – both the threading and the treadling; 2) structures that generally require some adjustment of the extension, to avoid too long floats; 3) structures that are only possible with more shafts; 4) combinations of structures, sometimes called hybrid.

Extending the Threading and Treadling from Four to More

Structures that fall in this category are many of the grouped weaves, which form blocks, with one warp and one weft (the “lacey weaves”), and the tied-unit weaves which form blocks with one warp, a background weft and a pattern weft; summer and winter is the only one on four shafts (discussed in the 3rd section).

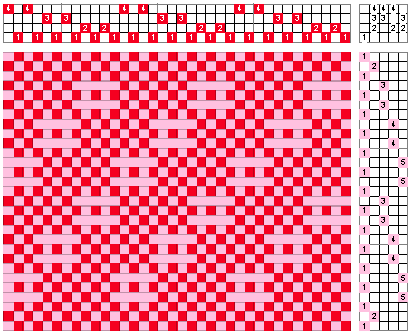

Example: Spot Bronson

On four shafts, there are three blocks, each made up of shaft 1 plus a pattern shaft. Blocks can be as long as we wish, limited by the float length, which, in turn depends on sett. Blocks cannot be combined as the float would just be extended. On eight shafts, there are seven blocks, and they can be arranged to form motifs as long as adjacent blocks are not combined.

From the drawdowns we see that the structure has been simply extended to 8 shafts with no changes. Plain weave across the fabric is treadled 1 vs. all other shafts; each block is treadled by covering with weft the warp ends on shaft 1 and plus the pattern shaft; on a sinking shed loom, we lower shaft 1 and the pattern shaft; on a rising shed loom, we lift all the pattern shafts except the one to be covered; that is, to weave block A threaded on shaft 2, we lower shafts 1 & 2 or we raise 3 & 4 on 4 shafts or 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 & 8 on 8-shafts.

Spot Bronson on 4 shafts

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

Spot Bronson on 8 Shafts

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

This simple extending allows for more design options.

Extending the Structure from Four to More with Some Adjustments

Structures that fall into this category are the twills and the supplementary weft weaves derived from twills, for example overshot (see May 2016 blog).

Example: Straight Twill

Twills are structures with one warp and one weft that forms staggered floats. A balanced straight twill, shown below, is the simplest on four shafts, balanced meaning that with every pick, two shafts are up and two shafts down, also called a 2/2 twill. Because every pick follows the same rules, the 2/2 twill is called regular and forms the characteristic slanted motif.

Straight Twill on 4 shafts

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

With 8 shafts, we can simply extend the threading and treadling as shown below, but this results in 6-thread floats, weft-floats on one side, warp-floats on the other. Whether a 6-thread float is acceptable depends on the sett, but there are more options that result in more visually pleasing twills.

Straight Twill Threading on 8 shafts

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

There are three options to adjust this twill: 1) change the tie-up to anchor the floats, maintaining the balanced twill; 2) change the tie-up to anchor the floats, but produce an unbalanced twill (similar to the 3/1 twill on 4-shafts); 3) change the tie-up to anchor the floats, so that the picks do not follow the same rule; this is an irregular twill, sometimes called fancy.

Below is a 2/1/2/3 straight twill, which is balanced: with every pick, 4 shafts are up (2 and 2) and 4 shafts stay down (1 and 3).

2/1/2/3 Straight Twill

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

Below is a 3/1/2/2 straight twill which is unbalanced: 5 shafts are up (3 and 2) and 3 shafts are down (1 and 2).

3/1/2/2 Straight Twill

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

Below is an irregular or fancy twill, which cannot be described by any sequence of up and down shafts, since each pick is different.

Irregular Straight Twill

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

In each of these cases, the floats are never more than 3-threads long, making for a stable fabric.

Structures Requiring More than Four

There are three common groups of structures that generally require more than for shafts: satins, most tied-unit weaves, and most turned drafts from supplementary weft weaves. We will discuss these.

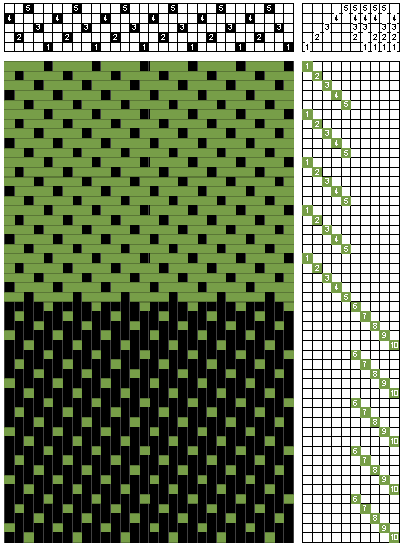

Example: 5-Shaft Satin

Satins require at least 5 shafts to be woven; they are unbalanced fabrics, one side predominantly weft-dominant, called sateen, the other warp-dominant, called satin. On four shafts, a 3/1 broken twill is sometimes called a false-satin because it resembles it, but in a true satin the floats are stitched or anchored intermittently with less pattern, especially with more shafts, which is why four can’t produce a true satin. (My May 2017 and June 2017 blogs are on this topic). With 8 shafts, we can have 7- and 8-shaft satins, in addition to 5.

Satin

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

The first half of the drawdown above shows the sateen side, which is the way the fabric is usually woven, only one shaft at a time to lift; the bottom of this fabric will be the satin side. The second half of the drawdown shows the satin side up, facing the weaver as the fabric is woven; the bottom of this fabric will be the sateen side.

Satins can showcase special yarns, making for an almost solid surface; care must be taken, however, because they can be heavy, packing nearly twice as much yarn as plain weave for the same size fabric. Using thin threads and light weight fibers solves the problem.

Unit Tied-Weaves: Tied Lithuanian

We have already mentioned that summer and winter is a unit tied weave that can be woven on four shafts. But this group really profits from more shafts; in fact, there are so many options, that some don’t even have names, but they are called by their classification described below, made popular by Donna Sullivan in her book Summer and Winter A Weave for All Seasons. First we apply it summer and winter on 4 shafts.

|

Summer and Winter Example |

Classification |

|

Single |

# of pattern shafts per block |

|

Two-tie |

# of shafts used for ties |

|

Unpaired |

Paired = ties next to each other |

|

1: 1 ratio |

Ratio of |

By this nomenclature, summer and winter is called single because each block uses one pattern shaft, 3 in block A, 4 in block B, see drawdown below; two-tie since shafts 1 and 2 are the ties; unpaired because the ties alternate with the pattern shaft in each block; a 1:1 ratio since each block has two ties and two pattern shafts, even though each block uses the same pattern shaft twice.

Summer and Winter on 4 shafts

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

From the drawdown we see that, in treadling, each block is woven with two pattern picks; the weft covers the threads on the pattern shaft and on one of the ties, then the other. In a sinking shed loom, the pattern shaft is lowered, in a raising shed loom, all other shafts are raised. The drawdown above is for a raising shed loom; to weave block A, threaded on shaft 3, the picks raised one of the tabbies, plus shaft 4, so 3 stays lowered to be covered.

In treadling, each pattern pick is followed by a tabby pick, treadled ties vs. pattern shafts; on 4-shafts that is 1 & 2 vs. 3 & 4; the tabby picks are not shown in the drawdown above, so the pattern is more obvious. This treadling is called “singles”, but there are more treadling options. (See RFTS in Shuttle Spindle & Dyepot #198 & #199, summer and winter 2019, respectively).

When summer and winter is woven on 8 shafts, it is still a single, two-tie, unpaired structure with a 1:1 ratio as shown in the drawdown below. As with 4 shafts, the tabbies are 1 & 2 vs. all pattern shafts; each block is woven with two picks, each tie-down shaft plus the pattern shaft, as in four shafts. Adjacent blocks can be combined on 4 and 8 shafts, but there are more options on 8 shafts.

Summer and Winter on 8 shafts

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

With more than four shafts, each of the parameters in the classification can be changed and increased; for example, we can have more shafts per block, or more ties.

Below is the drawdown of an example: Tied-Lithuanian, which is described by this classification.

Double: two pattern shafts per block (3 & 4; 5 & 6; 7 & 8).

Two-tie: two shafts for the ties, 1 and 2.

Paired: the ties, 1 and 2, are next to each other.

1:2 ratio: each block has the two ties and four pattern shafts, two repeated for each block.

In treadling, a tabby shot follows each pattern pick, not shown in the drawdown. The tabbies are all odd shafts vs. all even shafts.

The drawdown shown below is for a raising shed loom, thus alternate shafts are raised in order to cover the block with weft. When treadling the blocks, the odd tie-down shaft, 1, is raised with the odd pattern shafts not in the block threading. That, is, to treadle block A which uses pattern shafts 3 & 4, the odd pattern pick lifts 1 & 5 & 7. The other pattern pick for block A lifts the even tie-down shaft, 2, plus the even pattern shafts, 6 & 8, not found in the threading of block A.

Tied-Lithuanian

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

The treadling shown forms plain weave in the blocks not being woven, but blocks can be combined because the tie-down threads limit the floats.

Turned Drafts: Summer and Winter

We turn drafts by literally exchanging the threading with the tie-up/treadling, usually to avoid weaving with two shuttles. The supplementary weft becomes the supplementary warp. A drawdown that requires 6 treadles is turned into a structure requiring 6 shafts. Thus, most 4-shaft structures with a supplementary weft need more than four to be turned (an exception is Monk’s Belts).

Below is the drawdown of summer and winter on 4-shafts; it’s the same structure shown in the previous section, but this time the alternating tabbies are shown in the light green. There are six treadles needed to weave it, two tabbies (1 & 2 vs. 3 &4) and two treadle each for each block.

Summer and Winter

on 4 Shafts with Tabby

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

Below is the drawdown of the turned draft; the block motifs are also turned. Six shafts are needed, two for the tied down threads, two each for the two blocks.

On 8 shafts, a 3-block turned summer and winter could be woven, by adding shafts 7 and 8 to form the additional block, alternating with shafts 1 and 2.

Summer and Winter Turned

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

Combining Structures

We can think of our 8-shaft loom as being two looms: the front four shafts are one loom, the back four shafts another. Thus we can weave two structures together; the simplest way is to thread one structure on the front loom and another in the back loom in stripes, or the threading can alternate the two looms. Then we combine the treadling sequences.

While in principle this is easy to do, there can be some complications; in some cases, combining the two treadlings results in a sequence that requires more treadles that the loom has; in some instances, a skeleton tie-up may work, in others weaving the fabric upside down may make the skeleton tie-up more manageable.

Sometimes the combined treadling sequence is so long that weaving it can be daunting. Both of these cases are made much easier with a dobby, generally computerized now.

But a third complication can occur at the joints between one structure and the other, where the resulting floats are too long. Sometimes adjusting the floats results in a hybrid structure that is unique.

I use this method a lot in my work with more than 8-shafts with a computerized dobby. Sometimes the results are really fun, other times……

Happy Weaving!

Please email comments and questions to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..